97 Orchard: An Edible History of Five Immigrant Families in One New York Tenement (10 page)

Read 97 Orchard: An Edible History of Five Immigrant Families in One New York Tenement Online

Authors: Jane Ziegelman

Tags: #General, #Cooking, #19th Century, #History: American, #United States - State & Local - General, #United States - 19th Century, #Social History, #Lower East Side (New York, #Emigration & Immigration, #Social Science, #Nutrition, #New York - Local History, #New York, #N.Y.), #State & Local, #Agriculture & Food, #Food habits, #Immigrants, #United States, #Middle Atlantic, #History, #History - U.S., #United States - State & Local - Middle Atlantic, #New York (State)

In 1848, during the height of the Irish exodus, a self-promoting but charming Irishman named Jeremiah O’Donovan conducted a rambling tour of the eastern United States. The purpose of his trip was to hawk his masterpiece, a history of Ireland written in epic verse, a kind of Irish

Aeneid

with O’Donovan cast in the role of Virgil. O’Donovan kept a detailed travel log, and in 1864 it was published as a book.

A Brief Account of the Author’s Interview with His Countrymen

is essentially a glorified record of every Irishman he meets on his American wanderings, with special attention given to those who bought his book. Like the well-bred host at a dinner party, he is gracious to a fault. O’Donovan cites every customer by name (there are thousands of them), describing each with a thumbnail dossier, complete with occupation and place of birth, followed by a long-winded account of the customer’s most outstanding virtues.

A Brief Account

is exceedingly repetitive, but O’Donovan’s intention is more than mere entertainment. Aside from confirming his own reputation, O’Donovan is engaged in a public relations campaign on behalf of Irish-Americans, his attempt to counter negative attitudes directed at the immigrant community.

Buried in O’Donovan’s flood of adjectives are valuable kernels of information. For example, O’Donovan describes an extensive network of Irish “boardinghouses” and “hotels” (the distinction between the two is not always clear) that was already in place by the mid-nineteenth century. It covered the major East Coast cities like Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Baltimore, extended west to Cincinnati and south to St. Louis, but also reached into more out-of-the-way places like Kittanning, Pennsylvania, and Lawrence, Massachusetts. O’Donovan also tells us something about the boarders. They included seamstresses, bakers, priests, medicine salesmen, boot-makers—all of them Irish. Finally, the author imparts a clear sense of the pressing need for room and board among a foreign population that was unusually young, most of the immigrants single and alone in a foreign country. Every boardinghouse along his winding itinerary is filled to capacity, the guests “as thick in numbers as swallows in a sand bank.”

16

At many, O’Donovan is turned away for lack of space; others manage to shoehorn him in even if it means sharing a bed.

Many of the immigrant boardinghouses in New York had been carved from the city’s most venerable old homes. Sturdy brick structures with sloping tiled roofs, they were built in the mid-eighteenth century by the merchant princes who dominated the colonial economy. Many had names familiar to us today: Rutgers, Monroe, Crosby, Roosevelt are just a few. Around 1750, one of those merchants, William Walton, started construction on a fabulous new estate along the East River. Built from the most expensive materials—English timber, German tiles, Italian marble, and rare tropical woods for its interior—the structure stood three stories tall with views of the water. The house remained in the Walton family for several generations, but over time the wide-open expanse that once surrounded it was filled in with warehouses, factories, and other commercial structures. The neighborhood lost its cachet, and Walton’s descendants moved uptown to join the rest of fashionable New York. The once-grand interior was pillaged down to its shell. The ground floor was leased out to a German saloon-keeper, a plate-glass distributor, and a manufacturer of election flags. The main tenant, however, was Mrs. Connors, an Irish boardinghouse-keeper who rented the two upper floors.

A reporter who toured the old mansion in 1872 offers a quick glimpse into her kitchen, now housed in the former bedroom of the first Mrs. Walton. The original fireplace, he tells us, was ripped out and replaced with a monstrous black stove. Covered with various-size kettles and saucepans, it was presided over by the boardinghouse cook and her ever-bustling assistants. On the reporter’s visit, the kitchen was redolent with the smell of boiling cabbage and burned ham, both typically Irish foods. For the most part, however, Irish boardinghouse cooking was governed more by issues of economy than national origin.

The American boardinghouse is today close to extinction, but for most of the nineteenth century and part of the twentieth it was a very common living option. Writing about New York in 1872, the journalist James McCabe portrayed the city as one vast boardinghouse, a description that could also apply to Philadelphia, Boston, and other large cities. City dwellers regarded the boardinghouse as a necessary evil, a kind of residential purgatory that one must endure before moving on to other forms of housing. The woman who stood at the helm of this much-disparaged institution, the boardinghouse landlady, became a stock character in the popular imagination of nineteenth-century urban America, best known for her cheapness. She made regular appearances in newspaper and magazine stories, often seen prowling the public markets for third-rate ingredients. Here she is shopping at one of the city’s night markets, outdoor venues that catered to the budget-conscious:

That woman in the red reps underskirt, over-trimmed with velveteen, with very little bonnet but a jungle of artificial flowers and parterre of chignon, with almost the entire back of a gallipagos turtle in her tortoise-shell earrings…with the coarse hand in the soiled gloves, and the large greasy pocketbook tightly clasped—who is she? Her index finger is uncovered. She uses it as a convenient prod to go through meat and find out how tough it really is. Know her business? Of course she does. A slatternly Irish girl, maid of all work, with a basket big enough for a laboring man to carry, follows diligently at her heels. “Beef,” said the lady of the earrings very laconically, stopping full before the butcher. He looks at her for a moment, and with a long pole hooks down a piece of meat. It is a long, stringy portion of singularly unappetizing appearance.

17

Her purchase tells the story, in encapsulated form, of boardinghouse cuisine. As a rule, it was built on the most gristly cuts of beef, mutton, and pork, organ meats, including heart, liver, and kidney, salt mackerel, root vegetables, potatoes, cabbage, and dried beans—the core ingredients of urban working people. Boardinghouse cooks were known for their tough steaks, greasy, waterlogged vegetables, and insipid stews. Their signature dishes—hash, soup, and pies—were recycled from previous meals. The corned beef served for dinner might reappear as the next day’s breakfast steak, only to turn up again in a meat pie or a hash.

Though hash in its many forms (not just corned beef) has drifted to the culinary margins, at one time it was an American staple, especially among working people. Along with meat pies, its raison d’être was to use up leftovers. Economy-minded cookbooks of the period devoted whole chapters to hash. Miss Beecher, for example, the well-known domestic authority, gives eighteen hash recipes in her

Housekeeper and Healthkeeper

. Among them are ham hash with bread crumbs, beefsteak hash with turnips, and veal hash with crackers. Though hash was found in home kitchens and cheap restaurants, it was most closely tied to the boardinghouse. “Hash eaters,” a common nineteenth-century label, was a synonym for boardinghouse dwellers, while “boardinghouse hash” was a term used to denote any mixture—edible or not—of uncertain composition. The recipe that follows is adapted from

First Principles of Household Management and Cookery

by Maria Parloa, who taught at the Boston Cooking School. The ingredients are inexpensive, but the end product is extremely satisfying—just what a good hash should be.

F

ISH

H

ASH

One half pint of finely chopped salt fish, six good-sized cold boiled potatoes chopped fine, one half cup of milk or water, salt and pepper to taste. Have two ounces of pork cut in thin slices and fried brown; take the pork out of the fry pan, and pour some of the gravy over the hash; mix all thoroughly, and then turn it into the fry pan, even it over with a knife, cover tight, and let it stand where it will brown slowly for half an hour; then fold over, turn out on the platter, and garnish with the salt pork.

18

1836 was a watershed year in the culinary history of New York. Before that time, the city had relatively few public eating houses aside from taverns, which concentrated more on fluids than solids. Meals were generally consumed at home, with men returning from their place of work at midday, and again in the evening for supper. New York was much smaller then, so commuting twice a day was manageable, the distance between home and work no greater than a fifteen-minute walk. Public dining was reserved for the rich, or, paradoxically, the poor who took their meals at “coffee and cake shops”—a misleading name, since they also served pork and beans, hash, pies, and other low-budget dishes. Open twenty-four hours a day, their customers were laborers, newsboys, petty criminals, firemen, and other night workers, people of limited means with few eating options. Known for their “dyspepsia-laden cake,” “oleaginous pork,” and “treacherous beans,” they were places to avoid if possible. As the city stretched northward, it began to divide itself amoeba-style into an uptown residential quarter and a downtown business district. Geographically cut off from their uptown homes, businessmen working in Lower Manhattan needed to be fed. In 1836, an Irishman named Daniel Sweeny opened a cheap eating house geared to the downtown worker of “medium class.” Though prices were low (6 cents a plate), the food was decent and nourishing, the ser vice efficient, and the surroundings clean. Sweeny’s menu offered a fairly broad selection of nineteenth-century staples: oysters, roast beef, corned beef, boiled mutton, pork and beans, with pies and puddings for dessert. The restaurant was an immediate success, filling a gap in the city’s culinary needs which no one before him had identified.

Sweeny’s biography is emblematic of the striving immigrant. Born in Ireland in 1810, he emigrated to New York as a teenager, amassing a small fortune as a water vendor. (This was before the construction of the Croton aqueduct, when water was still hauled by bucket from a downtown reservoir.) He learned the restaurant business by working as a waiter. One of his customers was Horace Greeley, editor of the

New York Tribune

, who supposedly urged Sweeny to open his own eating house, which he did. With the money earned from his restaurant, Sweeny went on to larger, more ambitious projects, including the eponymous hotel that became a social hub for prominent Irish New Yorkers. Among his patrons were newspapermen, political bosses, and high-ranking members of the Catholic clergy. In the 1860s, when the hotel served as the unofficial New York headquarters for the Irish nationalist movement, Sweeny became host to revolutionary heroes like John Mitchell and Jeremiah O’Donovan Rossa. Sweeny staffed his establishments with immigrants like Joseph Moore, Irish waiters who banded together, often rooming in the same boardinghouse and helping one another find jobs.

Sweeny’s experiment in public dining encouraged a number of imitators, many of them Irish. Patrick Dolan immigrated to New York in 1846 and learned the restaurant business working in Sweeny’s hotel. When he turned twenty-five, Dolan opened a small lunch counter on Ann Street, which in time became a New York institution.

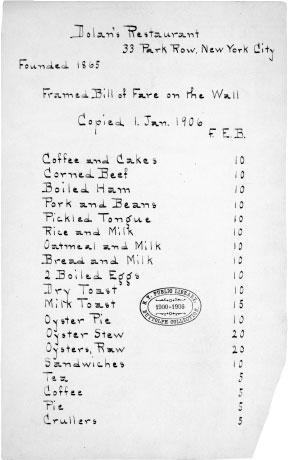

1906 menu from Dolan’s Restaurant, an Irish-run lunchroom.

Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations

Dolan’s Restaurant, which later moved to Park Row, was best known for two items. The first was “beef an,” New York shorthand for a slab of corned beef and a side of beans. (A less popular option was “ham an.”) The second was doughnuts, which New Yorkers called “sinkers.” James Gordon Bennet, publisher of the

New York Herald

and a regular at Dolan’s, was devoted to the oyster pie, as was Jay Gould, the railroad magnate. When Teddy Roosevelt returned to New York after his victory at San Juan Hill, he hired the Dolan’s cook to prepare a dinner for four hundred of his Rough Riders. Alongside the illustrious, Dolan’s fed the city’s boot blacks and newspaper boys, people with limited budgets who demanded cheap, good food, served in a hurry. A typical lunchtime crowd at Dolan’s was a startling mix of high and low, from street kids to robber barons, providing nineteenth-century New Yorkers with the kind of heterogeneous eating experience that no longer exists.

Joseph Moore most likely began his career in an Irish-owned restaurant similar to Dolan’s. Raised in Dublin, he may have worked there as a waiter before emigrating to the United States, arriving in New York with valuable work experience. But even if he knew the job in a generic way, waiting tables in a New York restaurant required specialized knowledge. By the 1860s, New York waiters had evolved their own peculiar on-the-job dialect, shouting to the cook orders that mystified the average customer. Here are just a few of them:

pair o’ sleeve buttons–two fish balls

white wings, end up–poached eggs

one slaughter on the pan–porterhouse steak

summertime–bread with milk