97 Orchard: An Edible History of Five Immigrant Families in One New York Tenement (13 page)

Read 97 Orchard: An Edible History of Five Immigrant Families in One New York Tenement Online

Authors: Jane Ziegelman

Tags: #General, #Cooking, #19th Century, #History: American, #United States - State & Local - General, #United States - 19th Century, #Social History, #Lower East Side (New York, #Emigration & Immigration, #Social Science, #Nutrition, #New York - Local History, #New York, #N.Y.), #State & Local, #Agriculture & Food, #Food habits, #Immigrants, #United States, #Middle Atlantic, #History, #History - U.S., #United States - State & Local - Middle Atlantic, #New York (State)

While the Ashkenazi cook retained elements of her Italian past, she also adopted local food habits, creating a new hybrid cuisine. Like her Gentile neighbors, she relied on dried peas and beans, porridge made from millet and rye, black bread, cabbage, turnips, dried and pickled fish, and, eventually, potatoes, a nineteenth-century addition to the Jewish diet. A shared dependence on local resources created broad similarities between the two kitchens, Jewish and Gentile. More interesting, however, is the cross-over of specific dishes, a process helped along by the Jewish merchant, a crucial point of contact between the two cultures. Among the dishes that made that journey are two Jewish staples. Before the Jews adopted it, the braided bread we know as challah was the special Sunday loaf of German Gentiles. German Jews adopted the braided bread, which was originally made from sour dough, and renamed it

berches

, a term derived from the Hebrew word for “blessing.” On the Sabbath table, the

berches

symbolized the offerings of bread once made to the

Kohanim

, the priests who served in the ancient temple. When a piece of bread was torn from the loaf and dipped in salt, it referred back to the sacrifices of salted meat at the temple altar.

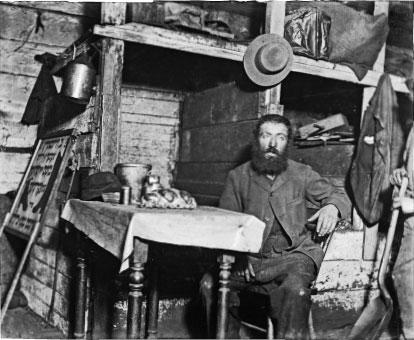

Even the poorest Jews celebrated the Sabbath with challah, the traditional braided loaf. Here, an immigrant prepares for the Sabbath in a Ludlow Street coal cellar, 1900.

Library of Congress: 209 “Ludlow St. Hebrew making ready for the Sabbath Eve in his coal cellar—2 loaves on his table, c. 1890,” Museum of the City of New York, The Jacob A. Riis Collection

Challah offers just one example of how borrowed foods could be reborn, their former lives erased from memory. Gefilte fish followed a similar path. The idea of a reassembled fish comes straight from the imagination of the medieval court cook, a master of visual trickery. Descriptions of medieval banquets are brimming with all manner of reassembled animals, from deer to peacock, brought to the table in their original skins. Following in that same tradition, gefilte fish was a creation of the court cook intended for the aristocratic diner. Here, for example, is a recipe from a sixteenth-century cookbook by the German court cook, Marx Rumpolt:

S

TUFFED

P

IKE

Scale the fish and remove the skin from head to tail; cut the meat off from the bone and chop it fine with a bit of onion; add a bit of pepper, ginger, and saffron, also fresh, un-melted butter and black raisins, egg yolk, and a bit of salt. Fill the pike with this mixture, replace the skin, sprinkle on some salt, place it in a pan and roast it. Make a sweet or sour broth under it and serve either warm or cold.

5

Recipes very similar to Rumpolt’s can be found in German-Jewish cookbooks from the mid-nineteenth century. As it traveled from one culture to another, gefilte fish, much like challah, was invested with a new iconography. But where challah looked to the Biblical past, gefilte fish became a symbol of the messianic banquet awaiting the Jews in paradise where, according to the Torah, the righteous shall dine on the flesh of the Leviathan. On the Sabbath table, gefilte fish was the Leviathan, that giant sea creature, a taste of paradise on earth.

In the second half of the nineteenth century, East Side Jews like Mrs. Gumpertz continued the gefilte fish tradition, preparing it in the old style, much like Rumpolt had four centuries earlier. A few decades later, a folksier version of gefilte fish seems to have taken its place. Prepared by cooks from Poland, Lithuania, and Russia, the chopped fish mixture was simply rolled into balls, simmered, then served cold with horseradish, the all-purpose Jewish condiment. With Jews from disparate countries all gathered in one neighborhood, subtle regional variations suddenly took on significance. Polish Jews, for example, seasoned their gefilte fish with sugar, where Lithuanians favored pepper. East Side Jews saw the sugar/pepper divide as a token of larger cultural differences between the Galiciana (Polish Jews) and the Litvaks (Lithuanians and Latvians), using it in conversation as a kind of code. So, if an East Sider wanted to know what part of the world a fellow Jew came from, he could ask, half-jokingly, “How do you like your gefilte fish, with sugar or without?”

Here’s a classic version of gefilte fish from the

International Jewish Cook book

, a dish of surprising delicacy to anyone who has tasted the mass-produced version found in the kosher aisle of your local supermarket:

G

EFILLTE

F

ISCH

Prepare trout, pickerel, or pike in the following manner: After the fish has been scaled and thoroughly cleaned, remove all the meat that adheres to the skin, being careful not to injure the skin; take out all the meat from head to tail, cut open along the backbone, removing it also; but do not disfigure the head and tail; chop the meat in a chopping bowl, then heat about a quarter of a pound of butter in a spider, add two tablespoons chopped parsley, and some soaked white bread; remove from the fire and add an onion grated, salt, pepper, pounded almonds, the yolks of two eggs, also a very little nutmeg grated. Mix all thoroughly and fill the skin until it looks natural. Boil in salt water, containing a piece of butter, celery root, parsley, and an onion; when done, remove from the fire and lay on a platter. The fish should be cooked for one and one-quarter hours, or until done. Thicken the sauce with yolks of two eggs, adding a few slices of lemons. This fish may be baked but must be rolled in flour and dotted with bits of butter.

6

By the mid-nineteenth century, a distinct form of Jewish life had evolved in East Prussia, the region where Natalie Gumpertz spent her first twenty-odd years. The Jews here were thinly scattered in small towns and villages, representing only a tiny fraction of the local population. Out of two million East Prussians, fourteen thousand were Jews. Dispersed as they were, East Prussian Jews lacked the critical mass to sustain the kinds of Jewish institutions found farther east in the larger, more-bustling Polish shtetlach. The town of Ortelsburg, East Prussia, where Natalie was born, was a sleepy market town, its Jewish population never much larger than that of a single East Side tenement. Too small and too poor to support a Jewish school, in the 1840s, the Ortelsburg Jews pooled their resources to build a synagogue, but never hired a permanent rabbi. No rabbi, no school. And yet, this remote outpost of European Judaism was of sufficient size to accommodate two Jewish-run taverns.

Among rural Jews, the local tavern was

the

preeminent social spot, especially for men, who came to play cards (a popular Jewish pastime), read the newspaper, and drink. Over a mug of beer or glass of schnapps, Jewish businessmen, from shopkeepers to horse dealers, cemented partnerships, found new customers, and made new contacts, not only with fellow Jews but with Christians too, who were likewise tavern customers. In many cases the taverns were attached to roadside inns that catered to Jewish merchants and traders. The inn provided them with a bed to sleep in and a stable for their horses, while the tavern kitchen, usually run by the tavern keeper’s wife, provided them with sustenance. On Saturday afternoons, whole families would stop by the tavern for a late lunch, paying for it when the Sabbath was over. At the start of the nineteenth century, the vast majority of German Jews lived in the countryside, but in the cities, too, Jews found their way into the hotel and restaurant business, one facet of their larger role in the food economy. Set apart from the wider culture by their distinct food requirements, the Ashkenazim relied on a vast network of butchers, bakers, vintners, distillers, traders, and merchants. The tavern-keeper belonged to this culinary workforce, supplying Jews with kosher food and drink in a public setting. Remember, too, that Christian-owned establishments were free to turn Jews away and often did. Jewish taverns and cafés, hotels, restaurants, and even Jewish spas, were the answer to widespread discrimination.

In the mid-nineteenth century, German Jews brought their experience in the hospitality business to America. At Lustig’s Restaurant in New York, nineteenth-century Jewish businessmen dined on German specialties like sweet-and-sour tongue, stuffed goose neck, and almond cake, all prepared to the highest kosher standards. Nicknamed the Jewish Delmonico’s, the Mercer Street restaurant stood in the heart of the old dry-goods district. Restaurant patrons were observant Jews from around the city, mainly wealthy merchants, who congregated at Lustig’s for the refined kosher cooking, but also for the traditional ambience.

In the Lustig’s dining room, with its bare wood floor and simple furnishings, customers performed the food-based rituals inseparable from the traditional Jewish dining experience. Like a visiting anthropologist, a New York reporter wrote up his observations of the lunchtime scene:

As each customer came in, he would take off his overcoat, hang it up, and then go to the washstand and wash his hands, looking very devout in the meantime and moving his lips in rapid muttering. He was repeating in Hebrew this prayer: “Blessed be Thou, O Lord our God, king of the universe, who hast sanctified us with Thy command, and has ordered us to wash hands.” Having thus performed his first duty, he took his seat and ordered his dinner.

The close of the meal was marked by the same kind of singsong praying that had opened it. In between, diners performed other curious acts, like dipping their bread into salt and praying over that as well. Also odd was how none of the customers removed their hats, a clear breach of dining etiquette. All in all, the experience was so foreign that the reporter exited Lustig’s feeling disoriented, like “a traveler returned from strange lands to his native heath.”

7

When he left his office and boarded the uptown streetcar, the typical Lustig’s customer returned to a traditional Jewish life. Beginning in the fall with Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year, he celebrated the full calendar of holidays, and every week observed the Sabbath. Friday evenings he went to synagogue, and Saturdays too, returning home at midday for lunch and a nap. The rest of the afternoon he devoted to Torah. While the man of the house prayed and studied, responsibility for guarding the purity of the home fell to his wife. A task that revolved around food, the work was relentless. Training began in childhood, when she was old enough to stand on a chair in her mother’s kitchen and help pluck the chicken or grate the potatoes. Over the years, she absorbed an immense store of food knowledge, allowing her to one day take control of her own kitchen. This happened the day she was married.

The traditional Jewish homemaker inherited her mother’s recipes along with her expert command of the Jewish food laws. Each day of her married life, as she shopped for groceries, or cooked, or even cleaned, she called on her knowledge of kashruth, ensuring every morsel of food served to the family was ritually pure. In other words, kosher. Such cooks could be found among New York’s German Jews, some on the Lower East Side, walking distance from Ansche Chesed on Norfolk Street, the Orthodox congregation founded by German immigrants in 1828. In the same urban population, however, were Jewish cooks with a radically new outlook on the dietary laws: women serving oyster stew, baked ham, and creamed chicken casserole, a full menu of forbidden foods.

The readiness to break away from tradition, more pronounced among Germans than any other Jewish group, had its roots in a wider cultural movement that began in Germany in the late eighteenth century, the Haskalah, or Jewish Enlightenment. For centuries, German Jews had lived as outsiders on the distant fringes of the wider Christian society. Their communities were self-governing and inward-looking, sealed off from the culture around them. But not entirely. Inspired by the European Enlightenment, eighteenth-century Jews began to question their own separateness. Men like Moses Mendelsohn, the eighteenth-century German scholar and philosopher, argued for the value of a secular education for Jewish school kids, a revolutionary suggestion at a time when education meant one thing only: the study of Torah. Mendelsohn’s ideas took hold, so by the middle of the nineteenth century Jewish children were learning to read and write in German, their passport to the larger world of secular thought. German Jews discovered Goethe and Schiller, along with German translations of the European classics. Even in the countryside, far from the intellectual ferment of the big cities, Jewish families spent the evenings reading aloud from Voltaire and Shakespeare.

The new openness in education encouraged other forms of change, particularly in the cities. Here, “modern-thinking” Jews developed a more relaxed approach to religious observance. On the Sabbath, shopkeepers kept their stores open. Men shaved their beards; women abandoned their traditional bonnets, trading them in for wigs, or went bareheaded. In their synagogues, modern-thinking Jews rejected traditional forms of worship, installing organs and choirs, the rabbi standing before his congregants in a long black frock and delivering sermons, very much like his Christian counterparts.