Read 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War Online

Authors: Benny Morris

1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War (30 page)

BOOK: 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War

6.87Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

ads

But he was equally critical of the Palestinians: he regarded them as incompetent and their elite as cowardly and ineffectual. 141 Both in Wadi Rushmiya and in the Lower City, the militiamen were poorly coordinated, lacked heavy weapons, and were short of ammunition. And through much of the battle, they were leaderless. Rashid Haj Ibrahim, the head of Haifa's NC, had left the city in early April. Ahmed Bey Khalil, the town's chief magistrate and sole AHC member (in effect, Ibrahim's successor as local leader), left "early on 21 April by sea." He was followed by Amin Bey `Izzadin, Haifa's militia commander, on the afternoon of 21 April, after the battle had begun, and by his deputy, Yunis Nafa`a, who left sometime (probably early) on 22 April. 142

Repeated pleas by the Arab political and military leaders for reinforcements from outside the city were stymied. At one point, British troops turned back a column attempting to reach the city from the village of Tira, to the south-"in the interests of humanity," said Stockwell (he argued that the reinforcements would merely have prolonged the fighting and increased the bloodshed, not altered the result).143 Throughout, the Haganah had had the advantages of the initiative, topography, command and control, and firepower (mortars). Nonetheless, its commanders were surprised by the speed of the Arab collapse. Stockwell estimated Arab losses during 21-22 April at a hundred dead and rSo to two hundred wounded, Jewish losses at sixteen to twenty killed and thirty to forty wounded. 144

During the morning of 22 April, the remaining Arab leaders called for a "truce." But the Haganah, having won, sought outright "surrender." Stockwell asked for its terms (which, to save Arab face, the Haganah agreed to call "truce terms"), amended them, and then arranged for a meeting-which all three sides understood was a surrender negotiation-at the town hall. Meanwhile, Thabet al-Aris, the local Syrian consul, prodded by local Arab notables, fired off a series of cables to Damascus asking for help; he warned that "a massacre of innocents is feared" or, alternatively, was already taking place. Responding, the Syrian and Lebanese governments called in the Brit ish heads of mission and demanded that the army step in and halt "this Jewish aggression." Syrian president al-Quwwatli hinted that, otherwise, the Syrian army might intervene. 145 But the diplomatic footwork accomplished nothing. The Syrian army was not going to move before the end of the Mandate.

Haifa's Arab notables were ferried to the town hall in British armored cars. The meeting convened at 4:oo PM. The Jewish leaders, who included Mayor Shabtai Levy, Jewish Agency representative Harry Beilin, and Haganah representative Mordechai Makleff, were, in Stockwell's phrase, "conciliatory," and agreed to further dilution of the truce terms. "The Arabs haggled over every word," recorded Beilin.146 The final terms included surrender of all military equipment (initially to the British authorities); the assembly and deportation of all foreign Arab males and the detention by the British of "European Nazis"; and a curfew to facilitate Haganah arms searches in the Arab neighborhoods. The terms assured the Arab population a ftiture "as equal and free citizens of Haifa."147 Levy reinforced this by expressing a desire that the two communities continue to "live in peace and friendship."

But the Arab delegation, headed by Sheikh Abdul Rahman Murad, the local Muslim Brotherhood leader, and businessmen Victor Khayyat, Farid Sa'ad, and Anis Nasr-a mixture of Muslims and Christians-declined to sign on and requested a break, "to consult." The Arabs were driven to Khayyat's house, where they tried to contact the AHC and, possibly, the Arab League Military Committee; they wanted instructions. Israeli officials were later to claim that the notables made contact and that the AHC had instructed them to refuse the surrender terms and to announce a general evacuation of the city. 148 But there is no credible proof that such instructions were given, and it seems unlikely.14' Indeed, a few weeks later, Victor Khayyat told an HIS officer: "There are rumors that the Mufti, the Arab Higher Committee, ordered the Arabs to leave the city. There is no truth to these rumors." I';" It appears that beyond Syrian and Lebanese efforts to persuade the British to intervene, no response was forthcoming from the AHC or Damascus to the notables' appeal.

When the notables reassembled at the town hall at 7:15 PM, they appear to have had no guidance from outside Palestine and were left to their own devices. The Arabs-now all Christians-"stated that they were not in a position to sign the truce, as they had no control over the Arab military elements in the town and that, in all sincerity, they could not fulfill the terms of the truce, even if they were to sign. They then said as an alternative that the Arab population wished to evacuate Haifa ... man, woman and child." i 5 I Without doubt, the notables were chary of agreeing to surrender terms out of fear that they would be dubbed traitors or collaborators by the AHC; perhaps they believed that they were doing what the AHC would have wished them to do. One Jewish participant at the meeting, lawyer Ya'akov Solomon, was later to recall that one of the Arab participants subsequently told him that they had been instructed or browbeaten by Sheikh Murad, who did not participate in the second part of the town hall gathering, to adopt this rejectionist position. 152

Be that as it may, the Jewish and British officials were flabbergasted. Levy appealed "very passionately ... and begged [the Arabs] to reconsider." He said that they should not leave the city "where they had lived for hundreds of years, where their forefathers were buried, and where, for so long, they had lived in peace and brotherhood with the Jews." The Arabs said that they "had no choice."153 According to Carmel, who was briefed, no doubt, by Makleff, his aide de camp, Stockwell, who "went pale," also appealed to the Arabs to reconsider: "Don't destroy your lives needlessly." According to Carmel, the general then turned to Makleff and asked: "What have you to say?" But the Haganah representative parried: "It's up to them [the Arabs] to decide."'S4

During the following ten days, almost all of the town's remaining Arab inhabitants departed, on British naval and civilian craft to Acre and Beirut, and by British-escorted land convoys up the coast or to Nazareth and Nablus. By early May, only about five thousand Arabs were left.

The majority had left for a variety of reasons, the main one being the shock of battle (especially the Haganah mortaring of the Lower City) and Jewish conquest and the prospect of life as a minority under Jewish rule. But, no doubt, the notables' announcement of evacuation, reinforced by continuous orders to the inhabitants during the following days by the AHC to leave town (accompanied by the designation of those who stayed as "traitors"), played their part.155 In addition, the attitude and behavior of the various Jewish authorities during the week or so following the battle was ambivalent.

As the shooting died down, the Haganah distributed a flyer cautioning its troops not to loot Arab property or vandalize mosques. I" On zs April, Haganah troops clashed with IZL men, who had moved into the (largely Muslim) neighborhood of Wadi Nisnas and were harassing the locals and looting, and ejected them. Two days before, several Haganah officers went down to Wadi Nisnas and Abbas Street and appealed to the inhabitants to stay, 157 as, on 28 April, did a flyer issued by the Haifa branch of the Histadrut: "The Haifa Workers Council advises you for your own good to stay in the city and return to regular work."158 American diplomats and British officials and officers, at least initially, reported that the Jews were making great efforts to persuade the Arabs to stay, whether for economic reasons (the need for cheap Arab laborers) or to preserve the emergent Jewish state's positive image.159

But more representative, at least after the first few days, was Beilin's response to the Arab notables' request for help in organizing the departure: "I said that we should be more than happy to give them all the assistance they require."'('" The Jewish authorities almost immediately grasped that a city without a large (and actively or potentially hostile) Arab minority would be better for the emergent Jewish state, militarily and politically. Moreover, in the days after 22 April, Haganah units systematically swept the conquered neighborhoods for arms and irregulars; they often handled the population roughly; families were evicted temporarily from their homes; young males were arrested, some beaten. The Haganah troops broke into Arab shops and storage facilities and confiscated cars and food stocks. Looting was rife. A week passed before services-electricity, water pipelines, and bakeries-were back in operation in the Arab areas. These factors no doubt influenced the decision during z3 April-early May by most of the town's remaining Arab families to leave, especially since Arab radio stations were continuously announcing an imminent Arab invasion and the defeat of the Zionists, after which, believed the refugees, they would return to their homes.

In the days after the fall of Arab Haifa the Haganah moved to secure the city's approaches. On z4 April Carmeli troops attacked the villages of Balad ash Sheikh, Yajur, and Hawassa, to the east. A British relief column arrived and advised the inhabitants to leave-which they promptly did, under British escort. No doubt, the fall of Haifa had dispirited and prepared them for their own evacuation. Two days later, the Haganah mortared Tira. The British intervened-but many villagers left nonetheless. (The village fell to the Haganah and was completely depopulated only in July.) On the night of 25 -26 April Carmeli troops took a hill overlooking Acre and mortared the town, but here, too, British troops forced a Haganah withdrawal, and the townspeople held on.

Without doubt, the conquest of Arab Haifa and the evacuation of its inhabitants had a resounding effect on all the communities in the north, as well as farther afield. The Jewish Agency commented: "The evacuation of Haifa [and Tiberias] was a turning point," which "greatly influenced the morale of the Arabs in the country and abroad." 161

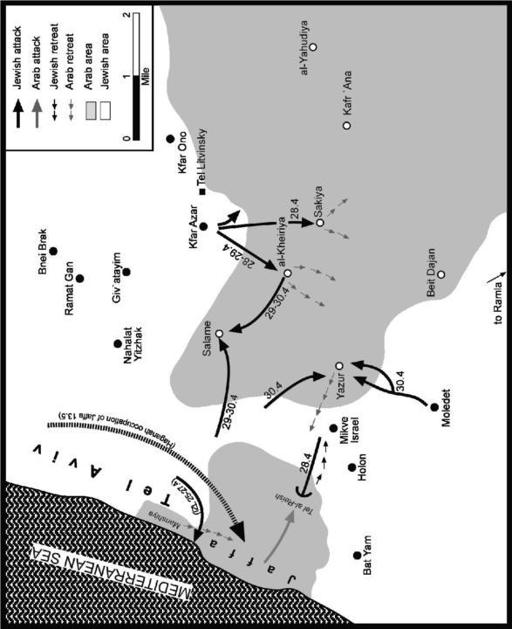

Jaffa

Palestine's largest Arab city, Jaffa, was assaulted and largely depopulated a few days after Arab Haifa (though it finally passed into Jewish hands only on 13-14 May). Tens of thousands of Jaffans had fled during the preceding months, and by April, the remaining inhabitants were "insecure ... and hopeless."' 6a The town suffered from a multiplicity of militia groups, with no unified command. By mid-April, most of the local leaders had left. 163 But at least two-thirds of the original seventy to eighty thousand inhabitants were still in place.

This time, it was the IZL rather than the Haganah. The Haganah brass had always regarded Jaffa, an Arab enclave in the midst of Jewish-earmarked territory, as a ripe plum that would eventually fall without battle; there was no need for a potentially costly direct attack. But news of the Haganah conquest of Haifa (and Tiberias) spurred the IZL to seek a victory of its own '164 and no objective was more attractive than Jaffa, which bordered on Tel Aviv, the IZL's main base of recruitment and operations, which for months had endured sniping from Jaffa's northern neighborhoods.

The IZL mustered its Tel Aviv area forces, some six companies, and on 25 April (without coordination with the Haganah) hurled them against Jaffa's northernmost, newest neighborhood, Manshiya. Much of the population had already fled to central Jaffa or farther afield. The poorly trained IZL fighters-who, though perhaps conversant with the terrorist arts, had never experienced combat-battled for three days from house to house, usually advancing by blowing holes through walls and pushing from house to house rather than along the enfiladed alleyways. The Arab militiamen, British observers noted, fought more resolutely than in Haifa. 16s The IZL suffered forty dead and twice that number wounded-but the Arab militias were crushed, their remnants, along with Manshiya's inhabitants, fleeing to the center of Jaffa. Haganah intelligence scouts subsequently found among the ruins Arab corpses "badly" mutilated by the IZL. 166 The arrival in Jaffa on 28 April of ALA reinforcements failed to save Manshiya. That morning the IZL troopers reached the sea at the southern end of Manshiya, cutting the district off from Jaffa's core. 167

BOOK: 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War

6.87Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

ads

Other books

The Death Collector by Justin Richards

Empties by Zebrowski, George

Liberty Begins (The Liberty Series) by James, Leigh

The Stranger You Know by Jane Casey

James and the Giant Peach by Roald Dahl

Mistaken by Fate by Katee Robert

Confessions of a Heartbreaker by Sucevic, Jennifer

Sewn with Joy by Tricia Goyer

SCARRED - Part 2 (The SCARRED Series - Book 2) by Kylie Walker

Decoration Day by Vic Kerry