Read 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War Online

Authors: Benny Morris

1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War (29 page)

BOOK: 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War

12.46Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

ads

THE TOWNS

In Operation Nahshon and the battles around Mishmar Ha'emek and Ramat Yohanan, the Haganah had conquered and permanently occupied or destroyed clusters of Arab villages. During the following weeks, the Jewish forces assaulted and conquered key urban areas, in effect delivering a deathblow to Palestine Arab military power and political aspirations. Arab Tiberias and Arab Haifa, Manshiya in Jaffa, and the Arab neighborhoods of West Jerusalem all fell in quick succession.

Tiberias

Tiberias, on the western shore of the Sea of Galilee, was a mixed town, with some six thousand Jews and four thousand Arabs. The Arab neighborhoods sat astride the shore-hugging road linking the Jewish settlements in the (Upper) Jordan Valley and the (Lower) Jordan and Jezreel Valleys, which were supplied from the Coastal Plain. Relations between the communities had been relatively good in the first months of the war, and the Arab leadership-basically the Tabari clan, which hailed originally from Irbid in Transjordan-had kept out foreign irregulars. In February, the Tabari-dominated National Committee and local Jewish leaders concluded a nonbelligerency agreement.

In March, in large measure because of Haganah provocations, relations deteriorated. 124 There were sporadic firefights between local militiamen, and the small Jewish Quarter in Tiberias's Arab-dominated Old City, by the lake, was cut off from the Jewish neighborhoods up the slope to the west. Many of the quarter's inhabitants moved out. For their part, the Arabs suffered from food shortages and their shops closed. By the end of the month several dozen foreign irregulars, apparently Syrians with "a German officer," had moved in.125 The Arabs periodically interdicted Jewish traffic along the south-north road. An explosion seemed inevitable. The British, with a small base nearby and about to withdraw, tried to maintain order but were disinclined to intervene forcibly. The Jews feared an influx of foreign irregulars and attack, the Arabs, Jewish conquest.

At some point during 9-II April, against the backdrop of a new flare-up, in which the local Haganah for the first time used mortars, the HGS decided to resolve the "problem" once and for all. On 12 April, a Golani Brigade company raided the hilltop village of Khirbet Nasir al-Din, which overlooked Tiberias's Jewish districts from the west. Twenty-two villagers died-the Arabs alleged "a second Deir Yassin"; atrocities apparently had been committed-and the rest of the inhabitants fled down the slope to Tiberias, sowing panic and fear in the population. 116 The fall of Nasir al-Din vitiated the possibility of reinforcement of Arab Tiberias by the ALA.

The Haganah brought in the Palmah Third Battalion and Golani units, some arriving by boat from Kibbutz `Ein-Gev, on the eastern shore of the lake, and, on the night of 16-17 April, struck hard. The troops dynamited a series of houses along the seam between the communities and barraged the Arab area with mortars. The British declined to intervene, and Arab pleas for help from outside went unheeded. It was all over in twenty-four hours. Some eighty Arabs were dead, "18" of them women;127 the Haganah suffered a handful of casualties. The Haganah occupied key Arab areas and demanded surrender. The Jewish commanders vetoed the idea of a "truce," and the Arab notables, perhaps on their own initiative, perhaps heeding British advice, decided on an evacuation of the population. 118 The British imposed a curfew and assembled a fleet of trucks. Then, on 18 April, escorted by British armored cars, the Arab population was trucked out in separate convoys eastward to Jordan and westward to ALA-held Nazareth. The empty Arab quarters were then thoroughly looted: "[It was as if] there was a contest between the different Haganah platoons stationed in Migdal, Ginossar, Yavniel, `EinGcv, who came in cars and boats and loaded all sorts of goods, refrigerators, beds, etc.... Quite naturally the Jewish masses in Tiberias wanted to do likewise.... Old men and women, regardless of age ... all are busy with robbery.... Shame covers my face," recorded one local Jewish leader.129 Arab Tiberias was no more.130 The evacuation of Arab Tiberias within days triggered the complete evacuation of a string of neighboring villages, among them al-`Ubeidiya, Majdal (the birthplace of Mary Magdalene), and Ghuweir Abu Shusha.

Haifa

Next to fall, and most significant, was Haifa. It had the second largest and most modern Arab community in Palestine and served as the country's major seaport and the unofficial "capital" of the north. What happened in Haifa would radiate across the Galilee. The city's Arab neighborhoods were concentrated along the seashore and around the port, at the foot of Mount Carmel. The newer, Jewish neighborhoods were perched up the slopes.

Tens of thousands of the city's original seventy thousand Arabs had fled during the previous months, and the Haganah had originally intended to occupy the Arab parts only when the Mandate ended. The Yishuv's leaders were keenly aware of Haifa's importance to the British-it was their main point of exit from Palestine-and realized that a premature offensive could result in Jewish-British clashes. In any case, once the British left, the town's Arab neighborhoods, by then probably demoralized, would surrender or fall in short order.

Yet as with the Haganah's general timetable, so with Haifa: the offensive was brought forward, partly because of the feeling that time was running out and the expected pan-Arab invasion was fast approaching; the Palestinian militias had to be subdued beforehand. On i8 April Galili told the Defense Committee that the Haganah was preparing "an operation ... in Haifa." 1 -11 And on 19 April a local Haganah representative, Abba Khoushi, had sounded out General Hugh Stockwell, the British commander in the north, about his attitude to a possible Haganah offensive in Haifa. The general had warned against it, implying that the army would have to respond. i as

Khoushi's soundings had been made in part in response to the increased pressure during the previous days by Arab militiamen against Haganah positions along Herzl Street and the Jewish neighborhood of Hadar behind it. Stockwell himself implied as much in his subsequent report. But the immediate, concrete trigger of the Haganah offensive was the abrupt withdrawal on zi April of British troops from their positions between the Jewish and Arab neighborhoods.

Just before dawn, the First Guards Brigade and auxiliary units abruptly pulled out of their downtown positions and withdrew to the harbor and to the neighborhood of French Carmel. Stockwell later explained that he had ordered the redeployment partly because of an increase in Arab and Jewish operations that had threatened the safety of his troops and partly because of the steady reduction in the number of troops he had available (as a result of the general withdrawal from Palestine). Immediately, spontaneous firefights erupted as Arab and Jewish militiamen jockeyed to occupy the abandoned British positions, which dominated key thoroughfares. Haganah troops oc cupied Haifa's airfield and the Kishon Railway Workshops; the Arabs took over the railway offices.

The Battle for Haifa, zi-zz April 1948

But the local Haganah brass, headed by Moshe Carmel, the commander of the Carmeli Brigade, while taken by surprise, immediately understood that the British redeployment afforded a strategic opportunity and reacted accordingly;'-33 the Arab response was disorganized and lackadaisical. Arab Haifa was defended by five hundred to a thousand armed militiamen; Carmel, with two battalions, had roughly the same number of troops'-34 but enjoyed centralized and effective command and control and better arms. The Haganah also enjoyed topographically dominant starting positions.

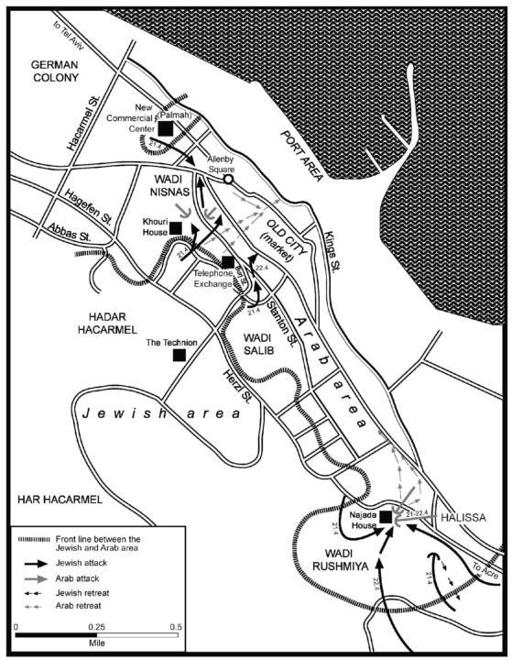

During the morning, Carmeli's commanders hastily hammered out a plan-mivtza bi`ur hametz (Operation Passover Cleaning)-to "break the enemy" by launching two efforts at once: one, from several directions, against the Arab-populated Lower City, and the other, toward Wadi Rushmiya, the Arab neighborhood to the southeast that sat astride the road linking Haifa and the Jewish settlements of Western Galilee. Troops and equipment were frantically mobilized and deployed.

The minor, easterly effort proved the more difficult. At r:30 PM an enlarged Haganah platoon, but with little ammunition and no food and water reserves, was sent to capture Najada House on Saladin Street, which dominated the Wadi Rushmiya quarter and bridge. The three-story stone-faced building was swiftly occupied. But for the next seventeen hours, the platoon was under constant sniping, machine gun, and grenade attack-indeed, under siege-from surrounding Arab buildings. The battle for Najada House precipitated a panic flight of inhabitants from Wadi Rushmiya westward, into the Lower City. Yet efforts by the Haganah command to link up with the platoon, whose losses mounted steadily, proved unavailing; the few armored cars that reached the building were unable to take out the wounded or silence the surrounding positions and, after delivering ammunition, withdrew. Carmel concluded that the platoon could be saved only if the more general, main operation soon to be unleashed against the Lower City was successful.

The Carmeli Brigade spent the rest of 21 April preparing the battle. A crucial shipment of new Czech rifles arrived from Tel Aviv that afternoon. They were quickly cleaned of grease and test-fired in the courtyard of Reali High School in Hadar. The troops then marched out, "through the streets of Hadar-Hacarmel. Along the way crowds watched ... [and] women threw flowers." The Haganah had emerged from underground and was behaving like an army. 13-; Soon after midnight, though short of ammunition, especially detonators and mortar bombs, the brigade was ready. At around i:oo AM, 22 April, three-inch mortars and Davidkas (the Yishuv's homemade, largely ineffective heavy mortars) let loose with a fifteen-minute barrage on the Lower City. Arab morale plummeted-though it was a relatively light barrage and not all the bombs actually exploded. (Indeed, as Carmel later wrote, "Whenever a bomb exploded and a column of black smoke rose above the city's alleyways-the members of the [mortar] team would go wild, dance, rejoice, hug each other, throw their hats in the air.")136 At the same time, a relief company set off for Najada House, on foot, battling through the alleyways. Arab militia resistance gradually collapsed and civilian morale cracked, the Arab population fleeing from the whole Halissa-Wadi Rushmiya area northwestward, into the Lower City. Shortly after dawn, the relief column reached the besieged platoon. The shooting there died down at Il:oo AM.137

Meanwhile, three other companies, one of them Palmah, in the early hours of 22 April, launched simultaneous assaults from Hadar northward and from the New Commercial Center (where the Palmah company was stationed) southward against major Arab strongpoints-the Railway Office Building (Khouri House), the telephone exchange, and the Arab militia headquarters, overlooking the Old Market-in the Lower City, and reached Stanton Street. The fighting, often bitter and hand-to-hand, inside buildings and from house to house, tapered off during the late morning. All the while, Haganah mortars peppered the Lower City with what one British observer called "completely indiscriminate and revolting ... fire. "133 By noon there was a general sense of collapse and chaos; in the Lower City and in Halissa smoke rose above gutted buildings and mangled bodies littered the streets and alleyways. The constant mortar and machine gun fire, as well as the collapse of the militias and local government and the Haganah's conquests, precipitated mass flight toward the British-held port area. By r:oo PM some six thousand people had reportedly passed through the harbor and boarded boats for Acre and points north.

A Palmah scout (disguised as an Arab) who had been in the Lower City during the battle later reported: "[I saw] people with belongings running toward the harbor and their faces spoke confusion. I met an old man sitting on some steps and crying. I asked him why he was crying and he replied that he had lost his six children and his wife and did not know [where] they were. I quieted him down.... It was quite possible, I said, that the wife and children had been transported to Acre, but he continued to cry. I took him to the hotel ... and gave him £P22 and he fell asleep. Meanwhile, people arrived from Halissa."139

Haj Muhammad Nimr al-Khatib, a prominent Haifa Muslim preacher (who was not in Haifa during the battle but spoke with refugees from the town), later described the scene: "Suddenly a rumor spread that the British Army in the port area had declared its readiness to safeguard the life of any one who reached the port and left the city. A mad rush to the port gates began. Man trampled on fellow man and woman [trampled] her children. The boats in the harbor quickly filled up and there is no doubt that that was the cause of the capsizing of many of them. "I40

Cunningham took a jaundiced view of the Haganah's tactics, as of the mindset of the Yishuv, which he saw them as reflecting. "Recent Jewish military successes (if indeed operations based on the mortaring of terrified women and children can be classed as such) have aroused extravagant reactions in the Jewish press and among the Jews themselves a spirit of arrogance which blinds them to future difficulties.... Jewish broadcasts both in content and in manner of delivery, are remarkably like those of Nazi Germany."

BOOK: 1948: A History of the First Arab-Israeli War

12.46Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

ads

Other books

Dreamers (The Dreamers Series) by Skye, Brooklin

Northern Star by Jodi Thomas

Seduction of Steel: The Complete Series by Charles, Laura

XXX: A Woman's Right to Pornography by Wendy McElroy

Code 15 by Gary Birken

Sea of Secrets: A Novel of Victorian Romantic Suspense by DeWees, Amanda

The River Rose by Gilbert Morris

Codename Prague by D. Harlan Wilson

Charmed Life by Druga, Jacqueline

Mallawindy by Joy Dettman