1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created (46 page)

Read 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created Online

Authors: Charles C. Mann

Tags: #Americas (North; Central; South; West Indies), #Expeditions & Discoveries, #United States, #Colonial Period (1600-1775), #History

The advent of synthetic rubber during the First World War failed to drive the Asians out of business. Despite the brilliance of industrial chemists, there is still no synthetic able to match natural rubber’s resistance to fatigue and vibration. Natural rubber still claims more than 40 percent of the market, a figure that has been slowly rising. Only natural rubber can be steam-cleaned in a medical sterilizer, then thrust into a freezer—and still adhere flexibly to glass and steel. Big airplane and truck tires are almost entirely natural rubber; radial tires use natural rubber in their sidewalls, whereas the earlier bias-ply tires were entirely synthetic. High-tech manufacturers and utilities use high-performance natural-rubber hoses, gaskets, and O-rings. So do condom manufacturers—one of Brazil’s few remaining natural-rubber enterprises is a condom factory in the western Amazon. With its need for materials that can withstand battle conditions the military is a major consumer—which is why the United States imposed a rubber blockade on China during the Korean War.

The blockade helped convince the Chinese of the need to grow their own

H. brasiliensis.

Alas, the nation had only a few areas warm enough for this tropical species. The biggest was Xishuangbanna (syee-schwong-ban-na, more or less), at the extreme southern tip of Yunnan Province, bordering Laos and Burma. A homeland for the Dai and Akha (Hani), two of China’s minority ethnic groups, Xishuangbanna Prefecture is China’s most tropical place. Although it comprises just 0.2 percent of the nation’s land, it contains 25 percent of its higher plant species, 36 percent of its birds, and 22 percent of its mammals, as well as significant numbers of amphibians and freshwater fish.

A few people had dabbled in rubber there as early as 1904, but the efforts had not been sustained. In the 1960s the People’s Liberation Army worked to turn the prefecture into a rubber haven. Xishuangbanna plantations were, in effect, army bases; entry was forbidden to outsiders. Outsiders included the Dai and Akha who lived nearby. As suspicious of the minorities in the mountains as the Qing, the Communists imported more than 100,000 Han workers, many of them urban students from faraway provinces, and put them into labor gangs charged with revolutionary fervor. “China needs rubber!” they were told. “This is your chance to use your hands to help your country!” Workers were awakened every day at 3:00 a.m. and sent to clear the forest, one former Xishuangbanna laborer told anthropologist Judith Shapiro, author of

Mao’s War Against Nature.

Every day we cut until 7:00 or 8:00 a.m., then ate a breakfast of rice gruel sent by the [Yunnan Army] Corps kitchen. We recited and studied Chairman Mao’s “Three Articles” and struggled against capitalism and revisionism. Then it was back to work until lunch break, then more work until 6:00. After we washed and ate, there were more hours of study and criticism meetings.

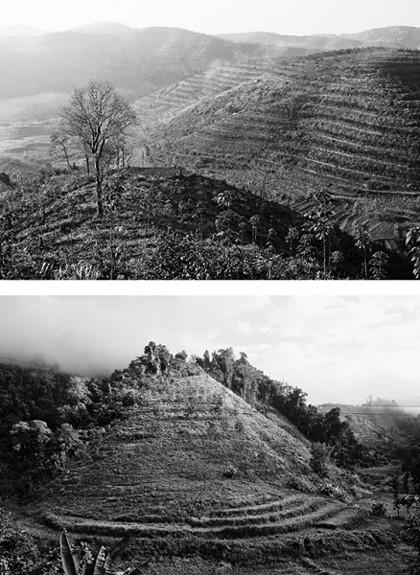

Sneering at botanists’ admonitions as counterrevolutionary, the youths repeatedly planted rubber trees at altitudes where they were killed by storms and frost. Then they planted them again in the exact same place—socialism would master nature, they insisted. The frenzy laid waste to hillsides, exacerbated erosion, and destroyed streams. But it didn’t actually yield much rubber. In the late 1970s the nation began its economic reforms. The educated young people fled back to their home cities, precipitating a labor shortage. Local Dai and Akha villagers were finally permitted to establish rubber farms. They were effective and efficient. Between 1976 and 2003 the area devoted to rubber expanded by a factor of ten, shrinking tropical montane forest in that time from 50.8 percent of the prefecture to 10.3 percent. The prefecture was a sea of

Hevea brasiliensis.

Unlike the flat Amazon basin, Xishuangbanna is a mass of hills. Planting on slopes exposed the trees to sunlight and ensured that they didn’t grow in pools of water, a constant risk in the Amazon because it damages the roots. In addition, according to Hu Zhouyong of the Tropical Crops Research Institute in Jinghong, the prefecture capital, the relative extremes of temperature let growers select for exceptionally robust trees that would produce more rubber in every circumstance. “Xishuangbanna is ahead of everywhere else in the world in terms of productivity,” Hu said to me.

Even as burgeoning China became the world’s biggest rubber consumer, its rubber producers were running out of space in Xishuangbanna—every inch of land was already taken. They looked enviously over the border at Laos; with about six million people in an area the size of the United Kingdom, it is the emptiest country in Asia. A few villages in northern Laos had begun planting as early as 1994. But the real push didn’t begin until the end of the decade, when China announced its “Go Out” strategy, which pushed Chinese companies to invest abroad. The country had already changed the old military farms into private enterprises—corporations with abundant political clout. As part of Go Out, Beijing announced that it would treat rubber growing in Laos and Myanmar as an opium-replacement program, making the former military farms eligible for subsidies: up to 80 percent of the initial costs for companies to grow rubber across the border, as well as the interest on loans. In addition, it would exempt incoming rubber from most tariffs. (Which companies are receiving the money is unclear; “the subsidy distribution process,” economist Weiyi Shi told me, “lacks transparency and appears to be plagued with cronyism.”)

Duly incentivized, companies and smallholders flowed over the border. They hired Dai and Akha who lived in China to work with their distant relatives in Laos. Most Laotians lived in hamlets without electricity or running water; schools and hospitals were a distant dream. Seeing a chance to improve their material conditions, villagers jumped starry-eyed on the rubber bandwagon, cutting deals with firms and farms in China. “In China, they were as poor as us,” one village head told me. “Now they are rich—they have motorcycles and cars—because they planted rubber. We want to have the same.”

No one knows exactly how much

H. brasiliensis

is now in Laos; the government doesn’t have the resources for surveys. According to anthropologist Yayoi Fujita of the University of Chicago, in 2003 rubber covered about a third of a square mile in Sing District, next to the border. Three years later it covered seventeen square miles there. Similar growth has occurred in many other districts. The Laotian government estimated that rubber covered seven hundred square miles of the nation by 2010, eight times more than it covered just four years before. And the pace of clearing will only accelerate, along with the effects of that clearing.

5

“To harvest a couple thousand square miles of rubber, you need a couple hundred thousand workers,” Klaus Goldnick, a regional planner in the northern provincial capital of Luang Namtha, said to me. “The whole province has only 120,000 people. The only solution is to bring in Chinese workers.” He said, “Many people here live off the forest. When the forest is gone, it will be difficult for them to survive.” He said, “Foreign companies are paying a concession fee”—about $1.50 per tree—“to the government. The more trees, the more fees.”

Most of the first plantations were created by villagers who knocked down a few acres on their own or worked with equally small plantations in China. Later the bigger Chinese operations moved in, among them the former state farms. Because rubber trees take seven years to mature, companies naturally want to make long-term arrangements with the people who plant and tend them. I was allowed to look at one of the resultant contracts, between the Chinese firm Huipeng Rubber and three hamlets in Luang Namtha Province.

Written in both Chinese and Lao, the contract consisted of twenty-four numbered paragraphs. Three were boilerplate: legal descriptions of Huipeng and the villages. Eighteen explained the rights and privileges of the company. One listed the villagers’ rights and privileges. In the confusion of the moment, I may have got the numbers slightly wrong—the papers were shown to me while a village head and the rubber agent were telling me their views, each in a different language. But it was impossible to miss that Huipeng’s executives had affirmed the contract with their signatures whereas the villagers had affirmed it by rolling their thumbprints onto the page. Each village would plant a certain amount of its land with rubber, the contract explained. Huipeng would in return improve both the roads within the village and the highway to it. But the firm could then sell its rights to the land at its own discretion and hire anybody it wanted to tend the trees, including people from China. Some 70 percent of the proceeds from rubber would go to the villages, “depending on the effective results of the planting”—a big loophole, it seemed to me. Contracts of this sort between companies and villages are common in China (the tobacco plots I visited in the Fujianese hill village in

Chapter 5

were governed by one). But such arrangements seemed less benign in Luang Namtha. To my eye the contract looked like the kind of document that emerges when one party has a lawyer looking after its interests and the other party doesn’t know what a lawyer is.

In Ban Songma, the next settlement down the road, the village leader who negotiated the contract was about thirty years old. On the day we met he wore a white T-shirt and soccer shorts with a Munich logo. Beside him stood his wife, holding a baby girl wrapped in a faded Hello Kitty blanket. I asked him the name of the rubber company, how much land the village was supposed to provide to it, and the split of the proceeds. He couldn’t answer these questions. This was not because he was stupid—he was obviously a shrewd, sparky man—but because the questions were beyond his frame of reference. To be a modern economic agent requires a huge set of habits, assumptions, and expectations. Few of them had been needed in Ban Songma even ten years before. Indeed, they may have been counterproductive. Venturing onto the clawed ground of global capitalism, the village head was as out of his element as Neville Craig was on the Madeira River. That he wanted the fruits of capitalism—Chinese motorbikes and Japanese televisions and nylon shorts emblazoned with the logos of European sports teams—didn’t make the likelihood of a happy outcome any greater.

Already Huipeng had imported Chinese workers to plant the seedlings. The village head didn’t know whether he and his neighbors would be taught how to graft trees themselves, or to tap latex, or to do the initial processing for rubber. But he did know that people who worked for the Chinese ended up with motorbikes, which liberated them from hours of walking up and down the steep hills. The baby in the Hello Kitty blanket will grow up knowing more than her father about the whirling new world Ban Songma is entering. Huipeng’s contract will be in force for forty years. It will be interesting to see at its end how that child regards the deal that her father signed.

THE END OF THE WORLD

The morning had been clear and bright, an ominous sign. On the pedestrian bridge that leads to the Xishuangbanna Tropical Botanical Garden I could see the faintest skirl of fog on the hills. Researchers had drawn their office curtains on the building’s sunny side. Founded in 1959, the garden grew up with Xishuangbanna’s rubber industry. Its scores of scientists monitored the impact of the refashioning of the regional ecosystem and didn’t like what they saw. “We all hate rubber,” one researcher told me. “But then we’re all ecologists here.”

Although the Golden Triangle receives as much as one hundred inches of rain a year, three-quarters of it falls between May and October. The rest of the year the forest survives largely on dew from morning fog. “Back in the 1980s and 1990s there was still fog at lunchtime,” XTBG ecologist Tang Jianwei told me. “Now it’s gone by eleven.” The “very obvious” change, he said, is a symptom of a profoundly altered hydrological regime.

Rubber is to blame, Tang said.

H. brasiliensis

usually sheds its leaves in January and new leaves begin budding in late March. The absence of leaves means that the forest has fewer surfaces to retain dew, which reduces water absorption during the dry season. Surface runoff rises by a factor of three—which in turn jacks up soil erosion by a remarkable factor of forty-five. Worse, the new leaves’ most intense growth occurs in April, at the dry season’s hottest, driest point. To propel growth, the roots suck up water from three to six feet below the surface. Tapping begins as the new leaves appear and continues until they fall. To replace the lost latex, the roots suck up still more water from the ground. How much water? Tang did some rough estimates with pen and paper. Half a kilogram of latex a day, twenty days a month tapping, 180 trees to the acre … good latex is 60 to 70 percent water … 4,400 pounds of water a year per acre. Rubber producers are effectively putting all the water in the hills into trucks and driving it away. “A lot of smaller streams are drying up,” he said. “Villages have had to move because there’s no drinking water.” Now spread this impact across Laos and Thailand, he said. It would be a slow-motion remaking of a huge area. “It’s not easy to tell what the effects would be,” Tang said.

Beginning to heed ecologists’ worries, Xishuangbanna effectively banned new rubber planting in 2006 by freezing all land rotation. The scheme is unlikely to have much effect. To begin with, as Shi notes, it seems to violate China’s newly reformed land laws. But even if Xishuangbanna farmers were to stop planting

H. brasiliensis

tomorrow, its area would keep rising—on their own, rubber trees are invading the remaining forest.