1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created (43 page)

Read 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created Online

Authors: Charles C. Mann

Tags: #Americas (North; Central; South; West Indies), #Expeditions & Discoveries, #United States, #Colonial Period (1600-1775), #History

Convinced they were building the Paris of the Americas, Belém’s newly rich rubber elite filled the cobbled streets with sidewalk cafés, European-style strolling parks, and Beaux-Arts mansions with (a concession to the tropics) the exceptionally tall, narrow windows that promote air circulation. Social life centered around the neoclassical Teatro de Paz, where rubber barons in box seats smoked cigars and drank cachaça, the distilled sugarcane liquor that is Brazil’s preferred high-alcohol beverage. Tall mango trees shaded the avenues that led to the harbor, where gangs of laborers sliced open the rubber lumps sent from upriver, looking for adulterants like stones or chunks of wood. After inspection, the rubber went into a series of immense warehouses that lined the shore like sleeping beasts. Rubber was everywhere, one visitor wrote in 1911, “on the sidewalks, in the streets, on trucks, in the great storehouses and in the air—that is, the smell of it.” Indeed, the city’s rubber district had such a powerful aroma that people claimed they could tell what part of the city they were in by the intensity of the odor.

Belém was the bank and insurance house of the rubber trade, but the center of rubber collection was the city of Manaus. Located almost a thousand miles inland, where two big rivers join to form the Amazon proper, it was one of the most remote urban places on earth. It was also one of the richest. Brash, sybaritic, and imposing, the city sprawled across four hills on the north bank of the great current. Atop one hill was the cathedral, a Jesuit-built structure with a design so austere that it looks like a rebuke to the monstrosity that dominated the next hill over—the Teatro Amazonas, a preposterous fantasia of Carrara marble, Venetian chandeliers, Strasbourg tiles, Parisian mirrors, and Glasgow ironwork. Finished in 1897 and intended as an opera house, it was a financial folly: the auditorium had only 658 seats, not enough to offset the cost of importing musicians, let alone the expense of construction. Wide stone sidewalks with undulating black-and-white patterns led downhill from the theater through a jumble of brothels, rubber warehouses, and nouveau-riche mansions to the docks: two enormous platforms that rode up and down with the river on hundreds of wooden pillars. State governor Eduardo Ribeiro aggressively boosted the city, laying out streets in a modern grid, paving them with cobblestones from Portugal (the Amazon has little stone), overseeing the installation of what was then one of the globe’s most advanced streetcar networks (fifteen miles of track), and directing the construction of three hospitals (one for Europeans, one for the insane, and one for everybody else). A celebrant of urban life, Ribeiro took part in everything his city had to offer, including its sybaritic whorehouses, in one of which he died amid what historian John Hemming delicately referred to as “a sexual romp.”

The city’s many brothels were largely for the rubber tappers and field operatives who staggered into Manaus after months of labor on remote tributaries. The owners and managers had mistresses, with whom they sported in the decadent style then fashionable. “Guests once knelt to lap champagne from the bathtub of the naked beauty Sarah Lubousk from Trieste,” Hemming wrote in his prodigious history of the region,

Tree of Rivers.

“The bather in the bubbly,” as Hemming called her, was the mistress of Waldemar Scholtz, a recent migrant who had become the city’s dominant rubber shipper—and the honorary consul from Austria. A few blocks away lived Aria Ramos, who led a celebrated double life as a carnival performer and a call girl; when she was slain in a hunting accident, her wealthy clients erected a life-size statue in the cemetery. Teeming bordellos, liquor-soaked cafés, cowboy-style barroom brawls—Manaus was the very model of a turn-of-the-century boomtown, from the warnings against the discharge of weapons on the street to the obligatory lighting of cigars with high-denomination banknotes.

So much wealth—wealth that literally

grew on trees

—in such a strategic material naturally attracted huge interest, domestic and foreign, economic and political. On the domestic side, the rubber trade came to be controlled by a baker’s dozen of export houses, which in turn were dominated by Scholtz & Co., owned by the man who owned the woman in the bathtub. Like Scholtz & Co., the export houses were usually run by Europeans—intense, pallid men whose waxed moustaches and pomaded beards helped them stand apart from the beardless Indian population. Classic middlemen, they unloaded and stored the rubber that came from the interior before sending it to the mouth of the Amazon, where other European-run merchant houses shipped it to Europe and North America. The rubber itself was obtained by yet another group of corporate entities. These controlled the most critical resource in the interior: human beings.

Because latex coagulates after it is exposed to air, tappers constantly had to recut trees, tending them daily through the four-to-five-month tapping season. And they had to process the latex into crude rubber before it dried and became difficult to work with. Both tapping and processing required large amounts of care and attention. And that care and attention had to occur in remote, malarial camps—the trees couldn’t be moved to more convenient, salubrious locations and the latex was too heavy to transport in its liquid state. Disease and European raids had harshly cut back the original indigenous population. Europeans had not replaced them. The ever-greater hunger for rubber was accompanied by an ever-more-desperate shortage of workers. Solutions to the labor problem emerged, many of them bestial.

At first the rubber boom seemed like a godsend—an arboreal jobs program—to the region’s perpetually impoverished people. Needing workers, rubber estates hired local Indians, shipped in penniless farmers from downriver, or shanghaied hands from Bolivia. Economic theory suggests that in a labor shortage the estates would have to promise high wages and comfortable working conditions. They often did, but the promised wages were offset by stiff charges for transportation, supplies, and board. Many supposedly well-paid men were never able to work themselves out of debt; malaria, yellow fever, or beriberi felled others. To keep the labor force from finding better offers—or running away—owners stored workers onsite in barren dormitories with armed guards. Neville Craig’s boss, the chief railroad engineer, visited the concessionaires who controlled the middle reaches of the Madeira. Living in three-story houses with sweeping verandas, the engineer wrote, the concessionaires were “surrounded, like medieval barons, with a retinue of Bolivian servants and their families.… These men are absolute masters of their peons.”

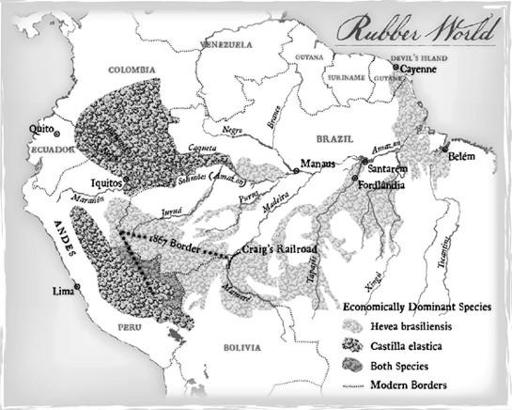

In the 1890s the boom went still further upstream, into the Andean foothills—areas that until then had been regarded as useless, and so left largely to their original inhabitants, most of whom had minimal contact with Europeans. Because

H. brasiliensis

can’t tolerate the cooler temperatures on the slopes, entrepreneurs focused on another species,

Castilla elastica,

which provided a less-valuable grade of rubber known as

caucho.

Although Indians tapped

Castilla

trees in Mesoamerica—the latex “emerges from

sajaduras

[the shallow cuts made when marinating meat] on the tree,” one Spanish eyewitness wrote in 1574—they did not in Amazonia. The incisions,

caucheiros

(

caucho

collectors) believed, let in diseases and insects that quickly wiped out

Castilla.

Rather than futilely try to protect the trees,

caucheiros

simply cut them down, gouged off the bark, and let the latex drain into holes dug beneath the fallen trunk. Sometimes collectors could obtain several hundred pounds of latex from a single tree, thus making up in volume for

caucho

’s lower price.

Click

here

to view a larger image.

Because

caucheiros

killed the trees they harvested, they naturally put a premium on being the first into a new area. The goal was to extract the most rubber in the least amount of time; every minute not at the ax was a minute when someone else was taking down irreplaceable trees. Work crews spent weeks or months trekking from tree to tree through steep, muddy, forested hills, carrying heavy loads of

caucho

from the areas they had just looted. Few people from outside the area were willing to come into the forest for this.

Caucheiros

thus turned to the people who already lived there: Indians. The situation invited abuse—and there are always people ready to take up such invitations.

Among them was Carlos Fitzcarrald, son of an immigrant to Peru who had changed his name from the hard-to-pronounce “Fitzgerald.” Beginning in the late 1880s Fitzcarrald forced thousands of Indians to work the

caucho

circuit. Brazilian writer and engineer Euclides da Cunha, who surveyed part of the western Amazon at this time, learned that at one point Fitzcarrald invaded a

Castilla

-rich area that was home to the Mashco Indians. Leading a squad of gunmen, da Cunha recounted, the

caucheiro

presented himself to the Mashco leader

and showed him his weapons and equipment, as well as his small army, in which were mingled the varied physiognomies of the tribes he had already subdued. Then he tried to demonstrate the advantageous alternatives to the inconvenience of a disastrous battle. The sole response of the Mashco was to inquire what arrows Fitzcarrald carried. Smiling, the explorer passed him a bullet from his Winchester. The native examined it for a long time, absorbed by the small projectile. He tried to wound himself with it, dragging the bullet across his chest. Then he took one of his own arrows and, breaking it, thrust it into his own arm. Smiling and indifferent to the pain, he proudly contemplated the flowing blood which covered the point. Without another word he turned his back on the startled adventurer, returning to his village with the illusion of a superiority which in a short time would be entirely discounted.

And indeed, half an hour later roughly one hundred Mashcos, including their recalcitrant chief, lay murdered, stretched out on the riverbank which to this day bears the name Playa Mashco in memory of that bloody episode.

Thus they mastered this wild region. The

caucheiros

acted with feverish haste. They ransacked the surroundings, killing or enslaving everyone for a radius of several leagues.… The

caucheiros

would stay until the last

caucho

tree fell. They came, they ravaged and they left.

More brutal still was Julio César Arana. The son of a Peruvian hatmaker, Arana came to exert near-total command over more than twenty-two thousand square miles on the upper Putumayo River, then claimed by both Peru and Colombia. Colombia had a heavier presence on the ground but was then convulsed by civil war. The Peruvian Arana took advantage of its inattention to push into the region, shoving aside rival

caucheiros.

Not wanting to lure laborers from other areas with high wages, he turned to indigenous people. At first they were willing to do some rubber collecting in exchange for knives, hatchets, and other trade goods. But when Arana asked for more they balked. So he enslaved them. By 1902 he had five Indian nations under his thumb.

Caucho

flowed from his land in ever-larger amounts.

Arana moved with his family to Manaus and established a reputation for quiet probity—he had the biggest library in town. Meanwhile his minions expanded his realm on the Putumayo, bribing government officials and killing his competitors. He controlled his slave force with a goon squad led by more than a hundred toughs imported from Barbados. Isolated in the forest and utterly dependent on Arana, the Barbadans executed every command they were given. No one other than Arana’s agents was allowed to enter the Putumayo from outside. Twenty-three custom-built cruise boats enforced his rule.

In December 1907 two U.S. travelers stumbled into the region. Encountering a

caucheiro

whose wife had been abducted by Arana’s thugs, the young men impulsively decided to help him confront the wrongdoers. Arana’s private police force beat and imprisoned them in one of the company’s bases, a charnel house where their guards, one of the travelers later recounted, amused themselves with “some thirteen young girls, who varied in age from nine to sixteen.” Outside, the “sick and dying” lay in untended heaps “about the house and out in the adjacent woods … until death released them from their sufferings. Then their companions carried their cold corpses—many of them in an almost complete state of putrefaction—to the river.” By claiming they were representatives of “a huge American syndicate,” the tourists managed to talk their way free.

One of them vowed to expose the situation. His name was Walter Hardenburg. The son of a farmer in upstate New York, he was a clever, restless man, self-taught as an engineer and surveyor. He had gone to the Amazon with a friend in the vague hope of seeking employment on the Madeira railroad, which a new group of Americans was trying to build. Hardenburg was not a crusader by temperament, as Hemming notes in

Tree of Rivers,

but what he saw enraged him. To document the abuses he traveled to Iquitos, Peru, on the headwaters of the Amazon. Located almost two thousand miles from the river’s mouth, it is often described today as the biggest city in the world that cannot be reached by road. It was then a boomtown port like Manaus, the main difference being that it was much smaller and completely dominated by Julio César Arana. At great personal risk Hardenburg spent a year and five months in Iquitos, finding witnesses to atrocities and obtaining their notarized testimony. With the last of his money he went to England in June 1908 to stir up public opinion. The first newspaper article appeared fifteen months later.