1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created (34 page)

Read 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created Online

Authors: Charles C. Mann

Tags: #Americas (North; Central; South; West Indies), #Expeditions & Discoveries, #United States, #Colonial Period (1600-1775), #History

Potatoes would not seem obvious candidates for domestication. Wild tubers are laced with solanine and tomatine, toxic compounds thought to defend the plants against attacks from dangerous organisms like fungi, bacteria, and human beings. Cooking often breaks down a plant’s chemical defenses—many beans, for example, are safe to eat only after being soaked and heated—but solanine and tomatine are unaffected by the pot and oven. Andean peoples apparently neutralized them by eating dirt: clay, to be precise. In the altiplano, guanacos and vicuñas (wild relatives of the llama) lick clay before eating poisonous plants. The toxins in the foliage stick—more technically, “adsorb”—to the fine clay particles. Bound to dirt, the harmful substances pass through the animals’ digestive system without affecting it. Mimicking this process, Indians apparently dunked wild potatoes in a “gravy” made of clay and water. Eventually they bred less lethal varieties, though some of the old, poisonous tubers still remain, favored for their resistance to frost. Bags of clay dust are still sold in mountain markets to accompany them on the table.

Andean Indians ate potatoes boiled, baked, and mashed as people in Europe and North America do. But they also consumed them in forms still little known outside the highlands. Potatoes were boiled, peeled, chopped, and dried to make

papas secas;

fermented for months in stagnant water to create sticky, odoriferous

toqosh;

ground to pulp, soaked in a jug, and filtered to produce

almidón de papa

(potato starch). The most ubiquitous concoction was

chuño,

made by spreading potatoes outside to freeze on cold nights. As it expands, the ice inside potato cells ruptures cell walls. The potatoes are thawed by morning sun, then frozen again the next night. Repeated freeze-thaw cycles transform the spuds into soft, juicy blobs. Farmers squeeze out the water to produce

chuño:

stiff, Styrofoam-like nodules about two-thirds smaller and lighter than the original tubers. Long exposure to the sun turns them gray-black; cooked into a spicy Andean stew, they resemble gnocchi, the potato-flour dumplings favored in central Italy. C

huño

can be kept for years without refrigeration, meaning that it can be stored as insurance against bad harvests. It was the food that sustained the conquering Inka armies.

Then as now, farming the Andes was a struggle against geography. Because the terrain is steeply pitched, erosion is a constant threat. Almost half the population cultivates some land with a slope of more than twenty degrees. Every cut of the plow sends dirt clods tumbling downhill. Many of the best fields—those with the thickest soil—sit atop ancient landslides and hence are even more erosion prone than the norm. Problems are exacerbated by the tropical weather patterns: a dry season with too little water, a rainy season with too much. During the dry season, winds scour away the thin soil. Heavy rainfall in the wet season sheets down hills, washing away nutrients, and floods the valleys, drowning crops.

To manage water and control erosion, Andean peoples built more than a million acres of agricultural terraces. Carved like stairsteps into the hills, the Spanish voyager Pedro Sarmiento de Gamboa marveled in 1572, were “terraces of 200 paces more or less, and 20 to 30 wide, faced with masonry, and filled with earth, much of it brought from a distance. We call them

andenes

” (platforms)—a term that may have given its name to the Andes. (Fifteenth-century Indians used more appropriate methods than those ordered by Mao in the twentieth century, and had much better results.)

On the flatter, wetter land around Lake Titicaca indigenous societies built almost five hundred square miles of raised fields: rectangular hummocks of earth, each several yards wide and scores or even hundreds of yards long. Separating each platform from its neighbor was a trench as much as two feet deep that collected water. During the night the trench water retained heat. Meanwhile, the complex up-and-down topography and temperature variation of the surface created slight air turbulence that mixed the warmer air in the furrows and the colder air around the platforms, raising the temperature around the crops by as much as 4°F, a tremendous boon in a place where summer nights approach freezing.

In many places raised fields were not possible and so Indians constructed smaller

wacho

or

wachu

(ridges), parallel crests of turned-up earth perhaps two feet wide, separated by shallow furrows of equal size. Because the Americas had no large domesticable animals—llamas are too small to pull a plow or carry human beings—farmers did all the work with hoes and foot plows, long wooden poles with short hafts and sharp stone, bronze, or copper tips and footrests above the tip. Making a line across the field, village men faced backward, lifting up their foot plows and jabbing them into the soil, then stamping on the footrest to gouge deeper. Step by backward step, they created ridges and furrows. Each man’s wife or sister faced him with a hoe or mallet, breaking up the clods into smaller pieces. Placed in holes atop the

wacho

were potato seeds or whole small tubers (each had to have at least one eye, from which the new potato would sprout). Sacred songs and chants paced the labor as the line of workers moved methodically down the field. Breaks were accompanied by mugs of

chicha

(maize beer) and handfuls of coca leaves to chew. When one field was done, villagers moved to the next, until everyone’s fields were ready—a tradition of collective work that is a hallmark of Andean societies.

Using a foot plow, Andean Indians break up the ground in this drawing from about 1615 by Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, an indigenous noble. Women follow behind to sow seed potatoes. (

Photo credit 6.2

)

Four or five months later, farmers swarmed into the fields, digging up the tubers and leveling the

wacho

for the next crop—often quinoa, the native Andean grain. Every scrap of the potato plant was consumed except the toxic fruits. The foliage fed llamas and alpacas; the stalks became cooking fuel. Some of the fuel was used on the spot. Immediately after harvest, families piled hard clods of soil into igloo-shaped ovens eighteen inches tall. Inside the oven went the stalks, as well as straw, brush, and scraps of wood (after the Spaniards came, people used cattle manure). Fire heated the earthen ovens until they turned white. Cooks pushed aside the ashes and placed freshly harvested potatoes inside for baking. Villagers in the heights still do this today—the stoves glow in the twilight, dotting the hills. Steam curls up from hot food into the clear, cold air. People dip their potatoes in coarse salt and edible clay. Night winds carry the bakery smell of roasting potatoes for what seems like miles.

The potato roasted by precontact peoples was not the modern spud. Andean peoples cultivated different varieties at different altitude ranges. Most people in a village planted a few basic types, but everyone also planted others to have a variety of tastes, each in its little irregular patch of

wacho,

wild potatoes at the margins. The result was chaotic diversity. Potatoes in one village at one altitude could look wildly unlike those a few miles away in another village at another altitude.

When farmers plant pieces of tuber, rather than seeds, the resultant sprouts are clones; in developed countries, entire landscapes are covered with potatoes that are almost genetically identical. By contrast, a Peruvian-American research team found that families in a mountain valley in central Peru grew an average of 10.6 traditional varieties—landraces, as they are called, each with its own name. Karl Zimmerer, now at Pennsylvania State University, visited fields in some villages with as many as twenty landraces. The International Potato Center in Peru has sampled and preserved more than 3,700. The range of potatoes in a single Andean field, Zimmerer observed, “exceeds the diversity of nine-tenths of the potato crop of the entire United States.” (Not all varieties grown are traditional. The farmers produce modern, Idaho-style breeds for the market, though they describe them as bland—they’re for yahoos in cities.)

In consequence, the Andean potato is less a single identifiable species than a bubbling stew of many related genetic entities. Sorting it out has given decades of headaches to taxonomists (researchers who classify living creatures according to their presumed evolutionary relationships). Learned studies of cultivated potatoes in Andean fields have divided them, variously and contradictorily, into twenty-one, nine, seven, three, and one species, each further sliced into multiple subspecies, groups, varieties, and forms. Four is probably the most commonly used species number today, though the dispute is anything but resolved. As for

S. tuberosum

itself, the most widely accepted recent study parcels it into eight broad types, each with its own name.

The potato’s wild relatives are no less confounding. In

The Potato,

a magnum opus from 1990, the potato geneticist J. G. Hawkes proclaimed the existence of some 229 named species of wild potato. That did not lay the matter to rest. After analyzing almost five thousand plants from across the Americas, Dutch researchers in 2008 winnowed Hawkes’s 229 species down to just ten fuzzily defined entities—“species groups,” as they put it—that bob like low, marshy islands in a morass of unclassifiable hybrids that extends from Central America down the Andes to the tip of South America and “cannot be structured or subdivided” into the classic species in biology textbooks. The description of the wild potato as a trackless genetic swamp was, the Dutch admitted, a view that their colleagues might find “difficult to accept.”

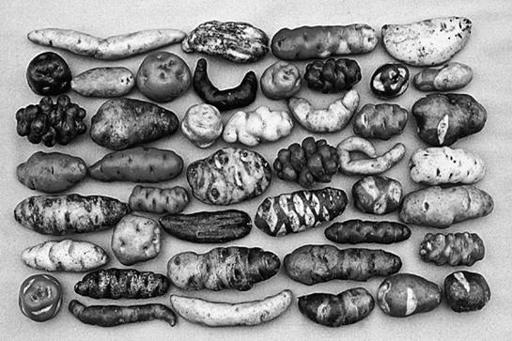

Andean natives bred hundreds of different potato varieties, most of them still never seen outside South America. (

Photo credit 6.3

)

None of this was apparent, of course, to the first Spaniards who ventured into the Andes—the band led by Francisco Pizarro, who landed in Ecuador in 1532 and attacked the Inka. The conquistadors noticed Indians eating these round objects and despite their suspicion sometimes emulated them. News of the new food spread rapidly. Within three decades, Spanish farmers as far away as the Canary Islands were growing potatoes in quantities enough to export to France and the Netherlands (then part of the Spanish empire). The first scientific description of the potato appeared in 1596, courtesy of the Swiss naturalist Gaspard Bauhin, who awarded it the name of

Solanum tuberosum esculentum,

which later became the modern

Solanum tuberosum.

Folklore credits Francis Drake with stealing potatoes from the Spanish empire during a bout of piracy/privateering. Supposedly he gave them to Walter Ralegh, founder of the luckless Roanoke colonies.

2

(Drake rescued the survivors.) Ralegh asked a gardener on his Irish estate to plant them. His cook is said to have served the toxic berries at dinner. Ralegh ordered the plants yanked from his garden. Hungry Irish picked them up from the refuse—hence, apparently, the statue of Drake in Germany. On its face, the tale is unlikely; even if Drake snatched a few potatoes while marauding in the Caribbean, they would not have survived months at sea.

The first food Europeans grew from tubers, rather than seed, the potato was regarded with fascinated suspicion; some believed it to be an aphrodisiac, others a cause of fever, leprosy, and scrofula. Ultraconservative Russian Orthodox priests denounced it as an incarnation of evil, using as proof the undeniable fact that potatoes are not mentioned in the Bible. Countering this, the pro-potato English alchemist William Salmon claimed in 1710 that the tubers “nourish the whole Body, restore in Consumptions [cure tuberculosis], and provoke Lust.” The philosopher-critic Denis Diderot took a middle stance in his groundbreaking

Encyclopedia

(1751–65), Europe’s first general compendium of Enlightenment thought. “No matter how you prepare it, the root is tasteless and starchy,” he wrote. “It cannot be regarded as an enjoyable food, but it provides abundant, reasonably healthy food for men who want nothing but sustenance.” Diderot viewed the potato as “windy” (it caused gas). Still, he gave it the thumbs-up. “What,” he asked, “is windiness to the strong bodies of peasants and laborers?”