1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created (29 page)

Read 1493: Uncovering the New World Columbus Created Online

Authors: Charles C. Mann

Tags: #Americas (North; Central; South; West Indies), #Expeditions & Discoveries, #United States, #Colonial Period (1600-1775), #History

Sweet potatoes in China are often eaten raw, the skin whittled off in a fashion that makes them somewhat resemble ice cream cones. (

Photo credit 5.2

)

The 1580s and 1590s, an intense point in the Little Ice Age, were two decades of hard cold rains that flooded Fujianese valleys, washing away rice paddies and drowning the crop. Famine shadowed the rains. Poor families were reduced to eating bark, grass, insects, and even the seeds found in wild-goose excrement. Chen Zhenlong and his friends seem initially to have thought of the

fanshu

—foreign tubers—as an amusing novelty; they gave them away as presents, a slice or two at a time, neatly wrapped in a box. (Botanically speaking,

fanshu

is a misnomer;

I. batatas

actually has a modified root, rather than a proper tuber.) As hunger tightened its grip, Chen’s son, Chen Jinglun, showed the

fanshu

to the provincial governor, to whom he was an adviser. The younger Chen was asked to conduct a trial planting near his home. Successful results persuaded the governor to distribute cuttings to farmers and instruct farmers how to grow and store them. “It was a great fall harvest; both near and far food was abundant and disaster was no longer a threat,” exulted the great-great-great-grandson. Near Yuegang, as much as 80 percent of the locals were living on sweet potatoes.

2

Governmental promotion of foreign crops was nothing new in Fujian. Sometime before 1000

A.D.,

Fujianese merchants brought in a novel type of rice—early-ripening Champa rice—from Southeast Asia. Because the new rice matured quickly, it could be planted in areas with shorter growing seasons. After intensive breeding, farmers created varieties that grew quickly enough to let them plant two crops a year in the same field—one of rice, then a second of wheat or millet. Harvesting twice as much from the same amount of land, Chinese farms became more productive than farms elsewhere in the world. The then-ruling Song dynasty actively promoted the new rice, distributing free seeds, publishing illustrated how-to brochures, sending out agents to explain cultivation techniques, and even providing some low-interest loans to help smallholders adapt. This aggressive adaptation and promotion of a new technology was a key reason for the nation’s subsequent prosperity, and its preeminence.

Still, Fujian was lucky that sweet potatoes arrived when they did. The crop spread through the province just in time for the fall of the Ming dynasty, which ushered in decades of violent chaos. Incoming Manchu forces seized Beijing in 1644, beginning a new dynasty: the Qing. The last Ming emperor hanged himself, and pretenders emerged to lead a rump state. Initially it was based in Fujian. In a disordered interlude, pieces of the Ming military splintered away and became, in effect,

wokou.

Meanwhile actual

wokou

took advantage of the confusion. To deny supplies to the Ming/

wokou,

the Qing army forced the coastal population from Guangdong to Shandong—the entire eastern “bulge” of China, a 2,500-mile stretch of coastline—to move en masse into the interior.

Beginning in 1652, soldiers marched into seaside villages and burned houses, knocked down walls, and smashed ancestral shrines; families, often given only a few days’ warning, evacuated with nothing but their clothes. All privately owned ships were set afire or sunk. Anyone who stayed behind was slain. “We became vagrants, fleeing and scattering,” one Fujianese family history recalled. People “simply went in one direction until they halted,” another said. “Those who did not die scattered over distant and nearby localities.” For three decades the shoreline was emptied to a distance inland of as much as fifty miles. It was a scorched-earth policy, except that the Qing scorched the enemy’s earth, not their own.

For Fujian, the coastal evacuation amounted to a spectacularly harsh version of the Ming dynasty’s ban on overseas trade. In the 1630s, before the political convulsions and the trade bans, twenty or more big junks went to Manila every year, each carrying hundreds of traders. During the evacuation, the number fell to as low as two or three, all illicit. Like the Ming trade bans, the Qing coastal clearance effectively turned over the silver trade to

wokou.

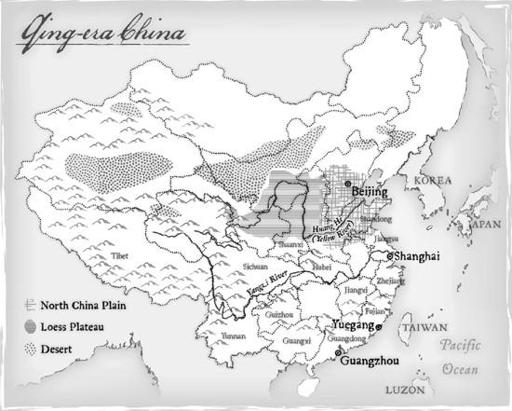

Click

here

to view a larger image.

As it happened, the trade was turned over to one pirate in particular: Zheng Chenggong, known in the West as Koxinga (the name is a corruption of a Chinese honorific). Born in Japan to a Japanese mother and a Fujianese Christian father who was a prominent pirate, Zheng had spent his life flouting Ming law. When the Qing came in, he realized that

wokou

were better off with the lackadaisical, corrupt Ming. He became an admiral in the rump Ming state and led an enormous sea-based assault on the Qing that came close to toppling the new regime. Afterward, he returned to piracy, amassing a fleet that one eyewitness, a Dominican missionary in Fujian, estimated at fifteen to twenty thousand vessels and an army of “a hundred thousand men at arms, all the necessary sailors, and eight thousand horses.” Based in a palace in Amoy (now called Xiamen), a city across the river from Yuegang, Zheng controlled the entire southeast coast—a true pirate king.

Manila’s traders, having no alternative, begged Zheng in 1657 to buy their silver. When his ships appeared in the harbor, the galleon trade resumed. Perhaps distracted by his running battle with the Qing, Zheng took longer than one would expect to realize that a) the Spaniards in the Philippines had no source but him for silk and porcelain; and b) he, Zheng, was a pirate with a large army. Not until 1662 did he dispatch the Dominican missionary—dressed in the rich robes of an imperial emissary—to Manila with a proposal to change the terms of trade. The Spaniards would give him all their silver, as before. In return, Zheng would not kill them. Panicked, the Spanish governor decided to expel the Chinese in the Philippines. Refusing to be ejected, they barricaded themselves in the Parián. As was by that point customary, Spanish troops forcibly rounded up the Chinese, slaughtering many and forcing the rest to leave Manila on jam-packed ships. The precaution turned out to be needless; just two months later, Zheng died unexpectedly, probably of malaria. His sons fought over their inheritance, and the Manila trade was left alone.

The Qing had ordered the coastal evacuation, but it had disastrous consequences for them, too. As the treasury official Mu Tianyan complained, closing down the silver trade effectively froze the money supply. Because silver was always being wasted, lost, and buried, the pool of Chinese money was actually shrinking. “Every day there is less and less to meet the demand, with no way to restore it,” Mu wrote to the emperor. When the money supply falls, each unit becomes more valuable; prices fall in a classic deflationary spiral. To stop the importation of silver “yet desire the wealth of fortune and convenience of use,” Mu asked, “how is this different from blocking a source of water while expecting to benefit from its flow?” Reluctantly agreeing, the Qing lifted the ban in 1681.

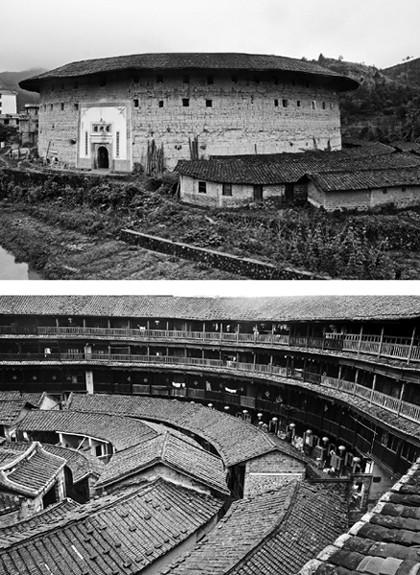

Meanwhile, though, coastal people had flooded into the mountains of Fujian, Guangdong, and Zhejiang. Inconveniently, these areas were already inhabited. Most of the inhabitants belonged to a different ethnic group, the Hakka, famed for their

tulou

—fortress-like complexes, usually but not always circular, whose earthen outer walls contain scores of apartments, all facing onto a central courtyard. (Today these amazing structures are a tourist attraction.) Decades before the expulsion, the Fujianese scholar Xie Zhaozhe had observed that the Hakka in the hills were packed into every scrap of available real estate:

There is not an inch of open ground.… Truly as someone once said, “Not a drop of water goes unused, and as much as possible even the most rugged parts of mountains are cultivated.” One could say that there isn’t a bit of land left.

Unable to support themselves, poor Hakka and other mountain peoples had been emigrating north and west for a century, renting uninhabited highland areas—terrain too steep and dry for rice—in neighboring provinces. They cut and burned the tree cover and planted cash crops, mainly indigo, in the exposed earth. After a few years of this slash-and-burn the thin mountain soil was exhausted and the Hakka moved on. (“When they finish with one mountain, they simply move on to the next,” the geographer Gu Yanwu complained.) As coastal refugees poured into the mountains, the highland exodus accelerated.

Landless and poor, the Hakka refugees were mocked as

pengmin

—shack people. Strictly speaking, shack people were not vagabonds; they rented land in the heights that was owned but not used by farmers in the more fertile valleys. Shifting from one temporary home to the next,

pengmin

eventually occupied a crooked, 1,500-mile stretch of montane China from the sawtooth hills of Fujian in the southeast to the silt cliffs around the Huang He in the northwest.

Neither rice nor wheat, China’s two most important staples, would grow in the shack people’s marginal land. The soil was too thin for wheat; on steep slopes, the irrigation for rice paddies requires building terraces, the sort of costly, hugely laborious capital improvement project unlikely to be undertaken by renters.

Thousands of

toulou,

clan dwellings of the Hakka, still dot the mountains of Fujian. Made from rammed earth mixed with rice stalks, they had no windows on lower floors as a defensive measure. (

Photo credit 5.3

)

Almost inevitably, they turned to American crops: maize, sweet potato, and tobacco. Maize (

Zea mays

) can thrive in amazingly bad land and grows quickly, maturing in less time than barley, wheat, and millet. Brought in from the Portuguese at Macao, it was known as “tribute wheat,” “wrapped grain,” and “jade rice.” Sweet potatoes will grow where even maize cannot, tolerating strongly acid soils with little organic matter and few nutrients.

I. batatas

doesn’t even need much light, as one agricultural reformer noted in 1628. “Even in low, narrow, damp alleys, where there is only a few feet of ground, if you can look up and see the sky, you can plant them there.”

In the south, many farmers’ diets revolved around the sweet potato: sweet potatoes baked and boiled, sweet potatoes ground into flour for noodles, sweet potatoes mashed with pickles or deep-fried with honey or chopped into stew with turnips and soybean milk, even sweet potatoes fermented into a kind of wine. In the west, China was a land of maize and another American import: potatoes, originally bred in the Andes Mountains. When the wandering French missionary Armand David lived in a hut in remote, scraggy Shaanxi, his meal plan would not have been out of place, except for a few garnishes, in the Inka empire. “The only plant cultivated near our cabin is the potato,” he noted in 1872. “Maize flour, along with potatoes, is the mountain peoples’ daily diet; it’s usually eaten boiled and mixed with the tubers.”

Nobody knew how many shack people were in the hills. Hoping, perhaps, that hiding the problem would avoid the need to solve it, Qing bureaucrats left them out of census reports. But all evidence suggests that the number was not small. In Jiangxi, Fujian’s western neighbor, the rigid, nit-picking provincial treasurer insisted in 1773 that the shack people, many of whom had lived in Jiangxi for decades, counted as actual inhabitants of the province and therefore should be included in the reports sent to Beijing. He dispatched field workers to enumerate every Hakka head and every Hakka shack. In rugged Ganxian County, they tallied 58,340 settled inhabitants, most in the main town of Ganzhou—and 274,280 shack people in the surrounding slopes. In county after county the story was repeated, sometimes with a few thousand wanderers, other times a hundred thousand or more. Hidden from the government, more than a million shack people had been slashing and burning their way across Jiangxi. And that, as the Qing court must have realized, was only one medium-sized province.