Zooman Sam

Authors: Lois Lowry

Lois Lowry

Illustrated by Diane de Groat

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY BOSTON

Walter Lorraine Books

Walter Lorraine Books

Text copyright © 1999 by Lois Lowry

Illustrations copyright © 1999 by Diane de Groat

All rights reserved. For information about permission

to reproduce selections from this book, write to

Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Company, 215 Park

Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lowry, Lois.

Zooman Sam / by Lois Lowry: Illustrated by Diane de

Groat

p. cm.

Summary: Four-year-old Sam's appearance as a

zookeeper at his nursery school's Future Job Day leads

him to a number of exciting activities and discoveries,

including reading.

ISBN 0-395-97393-7

[1. OccupationsâFiction. 2. Zoo keepersâFiction.

3. Nursery schoolsâFiction. 4. SchoolsâFiction.

5. LiteracyâFiction.]

I. Title.

PZ7.L9673Zo 1999

[Fic]âdc21 98-56006

CIP

AC

Printed in the United States of America

HAD

10 9 8 7 6 5 4

1For Bailey,

who loves Sam,

and for Grey,

who will

"What are you doing, Sam?" his mother called from the bottom of the stairs. "Dinner will be ready soon!"

"Nothing," Sam called back from his bedroom.

Nothing

wasn't exactly true. But it was what you said when it was too hard to describe the truth. The truth would have been "I'm looking at my clothes."

But then his mom would have said, "Why are you looking at your clothes? Is there something wrong with your clothes?" and she would have come up the stairs, and then Sam would have tried to explain

why

he was looking at all his clothes, and his mom would have noticed that

he'd made a mess in his closet because when he stood on a chair and pushed the hangers to one side, they all fell down, and now everything was in a heap, and Sam

planned

to pick them all up and hang them again, he just hadn't done it yet, but his mom wouldn't understand that, and she'd probably get mad, andâ

It was easier to say "Nothing."

"We're having chicken," his mom called, and he could hear her feet going back to the kitchen. Then he could hear the thumping of dog feet. Sam laughed a little. He knew it was Sleuth, the Krupniks' dog. Like most dogs, Sleuth understood "Come," and "Sit," though he didn't always choose to obey. But unlike most dogs, somehow Sleuth could recognize any word that related to food. And Sam's mom had said "chicken," so Sleuth, who spent most of his time sleeping (and probably dreaming of food), had leaped up to follow Mrs. Krupnik down the hall.

Sam didn't even care about chicken. He was too absorbed in his search. He began to poke through the pile of clothes on the floor of the closet.

He picked up a blue and white sailor suit and made a face. He remembered the wedding at

which he had worn it. His sister, Anastasia, had been a bridesmaid, and she wore a beautiful dress. She looked like a princess, or like a Barbie. Sam wouldn't have minded if he could have dressed like a prince, or a Ken. He would have worn a tuxedo. Sam thought tuxedos were cool.

But instead, his mom had made him wear that dumb sailor suit. It had short pants. His mom told him that it made him look like Popeye, and she had even drawn a marking-pen anchor tattoo on his arm, under the sleeve. But it wasn't true, about Popeye. The suit was just a dumb baby sailor suit, and everybody at the wedding said he looked cute. Sam didn't want to look cute. He wanted to look tough and mean. He decided he would never, ever wear the sailor suit again. He rolled it into a ball and threw it into the darkest corner of the closet, next to the folded-up stroller.

Sam noticed his Osh-Kosh overalls hanging from a hook. He stood on the chair and took them down. He liked his overalls. His sister had some just like them, and sometimes he and Anastasia wore their overalls on the same day. Their dad called them Ma and Pa Kettle when they wore their overalls.

Sam liked that. He didn't know who Ma and Pa Kettle were, but he liked the sound of those names.

But today the overalls were not what Sam needed. He thought about climbing up to rehang them on their hook, but that was too much bother. He rolled them up and threw them into the other corner of the closet, where they settled in a heap on top of his ant farm.

"Five minutes till dinner! Wash your hands, please!"

Hearing his mother's voice, Sam sighed. He looked at the clothes remaining in the pile that had fallen from the rod. Halfheartedly he picked up his bright yellow raincoat and thought about it for a minute. He liked his raincoat. But today it was not what he needed. He dropped the raincoat on the floor on top of his red snowsuit.

He looked toward the other side of the room, where he had already dumped the clothes he had taken from his bureau drawers. Socks and underpants and T-shirts and sweaters and jeans were strewn across the rug. His Superman pajamas dangled across the arm of the rocking chair, and a sweatshirt that said

HARVARD UNIVERSITY

had somehow landed on the head of Sam's old rocking horse.

None of the clothes were right. Sam felt like a failure. He felt like the biggest, dumbest poop-head in the world. He began to cry. He kicked the side of his bed in frustration, and his cat, who had been sleeping in her usual place beside Sam's teddy bear, woke in surprise. She jumped from the bed with an irritated swish of her tail, gave Sam a disgusted look, and left the room.

That was the final blow. Even his cat hated him. Sam began to cry harder.

"Everybody! Dinner's on the table! Come right now!"

Sam heard his father's chair creak and knew that his dad had pushed himself back from the desk in his study. He heard his dad's heavy footsteps head to the dining room.

He heard the clumping sound of the heavy hiking boots his sister liked to wear, and knew that Anastasia was coming down the stairs from her third-floor bedroom. Then she crossed the hall outside his room, and he heard her boots again as she headed, clumpety clump, down the second flight of stairs.

He smelled chicken.

"Sam! Hurry up!"

Still angry, still crying, Sam surveyed the wreckage of his room. His toes hurt because he had kicked his bed with his bare feet. His cat despised him. His friends would all laugh at him tomorrow. His teacher, Mrs. Bennett, would be nice, he knew, but secretly she would be thinking he was the biggest dumbo in the world.

Sam left his bedroom, slammed the door behind him, and stomped noisily down the stairs. He wailed in despair and frustration.

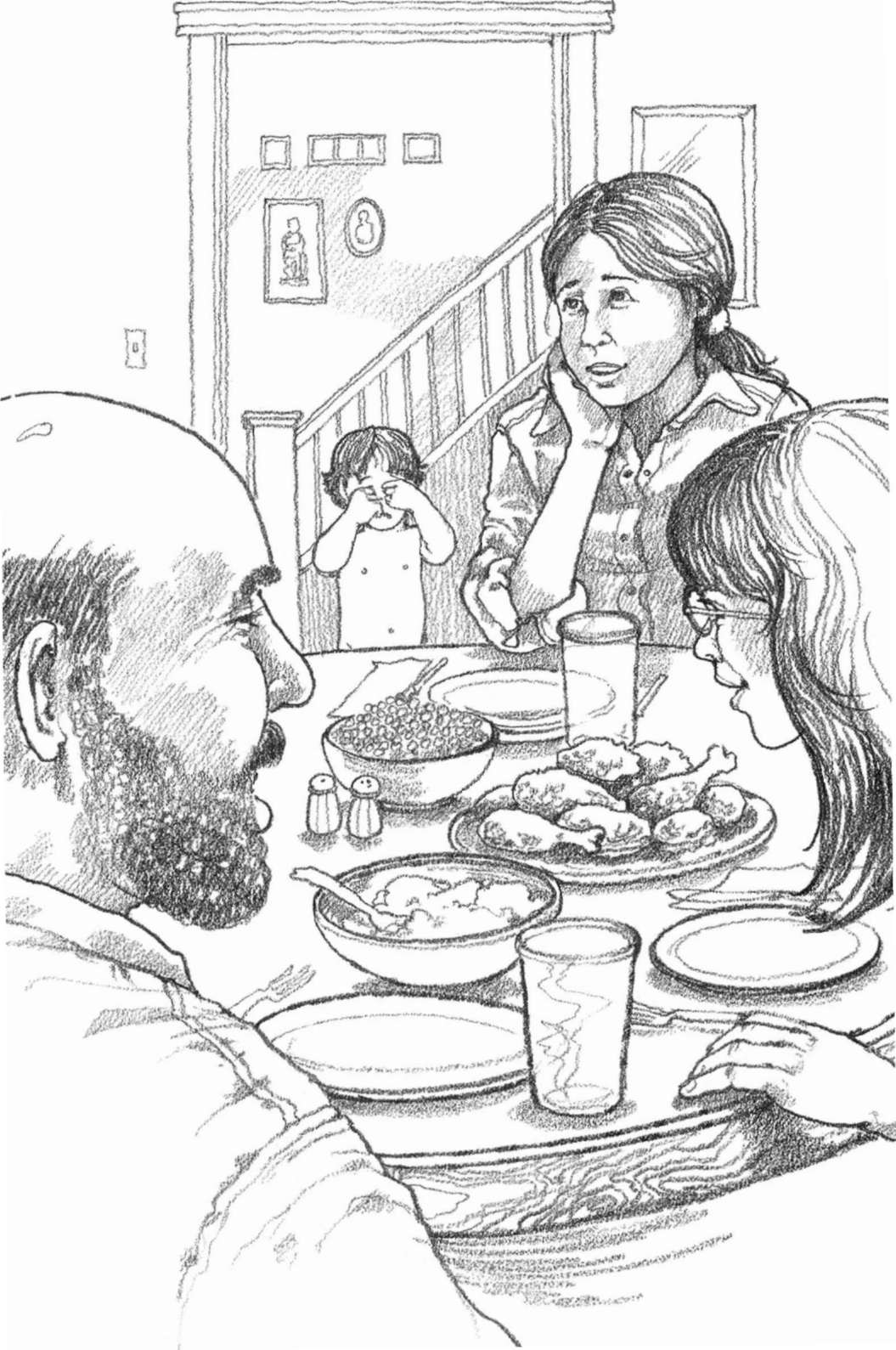

"Sam," said his mother as he entered the dining room, "what took you so long?" She was serving the chicken and passing the plates. She looked at Sam and blinked in surprise. "My goodness," she said.

"Sam, why are you crying?" asked his father. He was carefully mounding mashed potatoes on each plate that he took from Sam's mom. He looked at Sam and held a whole spoonful of potatoes in midair, forgetting to plunk it onto the plate.

His sister, Anastasia, was just about to dip a spoon into a bowl of peas. Anastasia was always in charge of vegetables, and that was a good thing, because she understood how important it was not to let certain vegetablesâlike beets,

especially beetsâtouch other things, like potatoes.

But Anastasia, without looking, dropped a whole spoonful of peas onto a plate, right on top of a chicken leg. Some of the peas fell from the plate onto the tablecloth, and no one even noticed.

They were all staring at Sam.

"Why are you

naked?

" Anastasia asked.

There was Chunky Monkey ice cream for dessert. That was both good and bad.

It was good because Sam loved Chunky Monkey. It was one of his favorites. So it made him feel pretty happy to have a big bowl of Chunky Monkey in front of him, and a spoon in his hand.

But it was bad because of its name. The name Chunky Monkey reminded Sam of his problem, his whole big problem, which he would never ever be able to solve; and thinking of his unsolvable problem made Sam feel like crying once again, even though he had already stopped crying long enough to eat his chicken.

He had even gotten dressedâwell, sort of dressedâbefore he climbed into his chair to eat his dinner. His mom had taken a big sweatshirt from a hook in the back hall, and dropped it over his head, and rolled up the sleeves. The sweatshirt had a picture of Beethoven on it. Beethoven was a man with a very frowny face, so his picture suited Sam perfectly. Sam was frowning, just like Beethoven.

"I'm going to be the dumbest one in my class," he told his family again.

"Of course you're not, Sam," his mom reassured him. "I wish Mrs. Bennett had let you know sooner, though, about Future Job Day."

"Well," Sam confessed, "she gave us a note to bring home."

"When did she do that?"

"Last week."

"For heaven's sake, Sam," his mother said, "why didn't you show me the note?"

Sam tried to remember what had happened to the folded note from Mrs. Bennett. "I had it in my pocket," he said.

"Yes? And then what? Did it end up in the washing machine?"

"I do that all the time, Sam," Anastasia said. "Usually with dollar bills. They come out of the

dryer all wadded up. It's hard to unfold them after they're washed and dried."

"No," Sam said, remembering. "I took it out of my pocket and I tried to fold it into an airplane."

"Why?" His father sounded interested.

"I don't know. I wanted an airplane."

"Well," his mother asked, "what happened to it after you folded it? Where

were

you when you made the airplane?"

"In the carpool car."

"Whose day was it to drive?"

Sam thought. He remembered sitting in the back seat, next to Adam, and next to Adam was Emily, and Emily said that she might throw up, but she didn't. And he remembered that Leah's wheelchair was folded in the way-back part. Leah was in the front seat, next toâ

"It was Leah's mom," Sam said.

"So," Mrs. Krupnik said with a sigh, "if I call Leah's mother, and ask her to look in the back seat of her station wagon, there on the floor, along with the crumpled-up McDonald's wrappersâ"

"There might not be McDonald's wrappers, Mom," Anastasia said. "Leah's mom might be very neat. She might clean her car every day."

"No, she isn't," Sam said. "She's messy, like

you. There's a whole lot of junk on the floor of her car. There's a rawhide bone that Leah's dog put there. And there's a Barbie doll, andâ"

"And a note from Mrs. Bennett, folded into an airplane. Darn it, Sam." Mrs. Krupnik sighed again.

"No, there isn't," Sam announced. "I flew it out of the car window, right near the library. It crash-landed in a bush."

Tomorrow was going to be Future Job Day at Sam's nursery school. The children were supposed to come, Mrs. Bennett had explained to them (and to their parents, in a note that had turned into an airplane and crash-landed in a bush), dressed the way they would dress as grown-ups, in whatever job that they hoped to have someday.