Zombie CSU (44 page)

“One cannot construe that zombies are immoral,” argues Rabbi Michael Shevack. “You

can

, quite the opposite, construe that they are perfectly moral, because they cohere with their own nature, and are acting, naturally, as themselves. Theologically, the only question is whether or not zombies are an aberration of God, and therefore, by their instinctive nature, however natural it is to them, they are abominations. This would certainly be implied by the fact that radiation, viruses, prions, interfere with the natural course of God’s Creation and therefore generate zombies. At best, zombies can be called amoral, with fairness to them, pending a serious discussion as to whether they are an aberration; but, like all aberrations, they were created out of creation, so, since Genesis has stated seven times (lest we forget it) that creation is GOOD—zombies must, in some fashion, have their right place and be part of that goodness, even in their fallen natures, if they have one. Nothing can arise unless the hand of God is in it. Including zombies. Unless of course, one believes in radical dualism, such as a competitor of Satan. I do not believe in such a radical dualism—so I believe that even zombies have their own blessed place, though what that place is as yet, I have not been able to discern.”

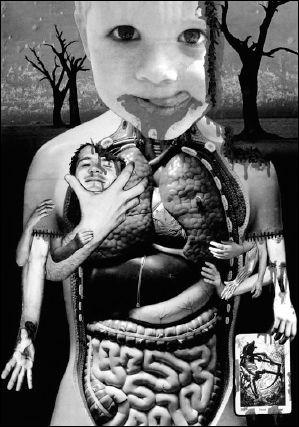

Art of the Dead—Geff Bertrand

Zombie Nightmare

“The first zombie movie I saw was the black and white

Night of the Living Dead

by George Romero. I was very young and my peepers were glued to the TV because the idea of the dead coming back to life was very bone chilling. I woke up screaming many a night after that and had to sleep with a night-light.”

And that brings up another and very subtle question, according to Rabbi Shevack: “Is a covenant between human beings and zombies possible? I wonder. After all, maybe they could be used to dispose of dead bodies, rather than turning what little open spaces we have now into graveyards. Maybe zombies can be harnessed as a way of getting rid of unwanted matter, and can actually be ecological-helpers. I don’t know, but it’s certainly food for thought.”

“I’m not a fan of labeling things as moral and immoral,” argues Professor Ladany, “because I think it takes away from individual freedom and cultural influence. I think of it rather as a healthy or unhealthy act. In the case of a predatory ghoul, if volition was not in his or her control, then it would be no more immoral than when any animal eats or attacks a prey or what seems to be a prey (e.g., a shark attack could be perceived as what happens when humans get in the way of sharks). Similarly, recall when Roy Horn (of Siegfried & Roy) was mauled by the tiger. People said the tiger went crazy. Chris Rock, however, pointed out that in actuality, ‘the tiger just went tiger!’”

Interfaith Pastor Joyce Kearney says, “Morality is a funny thing. If you get a bunch of people together—clergy and lay persons—and ask them about the morality of killing they’ll almost always tell you that it’s immoral and against God’s laws. They’ll cite the Commandments. Yet some of them either have served in the military or are family with someone who has; some of them may have killed in war, or while on duty as police officers. Some may hold the belief that assisted suicide is a mercy rather than murder. Some support capital punishment. Some will hold that killing in self-defense, or in defense of, say, a child, would be justifiable. If zombies existed and they attacked, what they would do would not be immoral because they have no thought and no soul and are therefore not bound by Commandments or any other religious or governmental law. People would fear zombies, and they would hate them, but I can’t see anyone pointing a finger and calling a zombie a sinner.”

On the morality of killing zombies, Dr. Gretz says, “The first question would be, ‘Would it be an illegal act?’ What would the police do? The supreme court would have to rule that the zombie was not really a person and had no legal protections and not only could, but should be put down (the level of dead before that happened would be interesting). Next, is the individual’s ‘spirit’ still residing in the body or has it left? If the spirit is gone—i.e., the person is literally dead in the religious sense—then there should be no problem once the Pope or some other authority said so. I think many people wouldn’t wait before trying to ‘kill’ the zombies. However, many others would probably hesitate long enough to become victims themselves.”

The Reverend Thomas Jefferson Johnson III, a Baptist minister from Trenton, New Jersey, weighs in on this: “If we delude ourselves into believing that we are a peaceful and nonviolent species—and all of history stands against that view—then we could never shoot a zombie even in defense because no matter what they are now they were once humans; but as I said, that would be delusional thinking at best, and at worst a barefaced lie. We are violent, and our church laws have tried, with varying degrees of success, to keep us from acting on our

nature

for the last six thousand years. As a man of God I would love to say that we are closer now than we’ve ever been to finally becoming a naturally moral people. But I just came back from Somalia where I was on a medical aid trip with the Red Cross. I’ve been in Iraq, and I said prayers over the butchered bodies of children in Rwanda. If we would do such things to each other—often in the name of God—then what makes you think we would even flinch when it comes to pulling the trigger on a zombie?”

Like most issues this one defies easy explanations.

“Consider this,” says Rabbi Shevack, “Rabbi Akiba,

8

whose dictum became definitive in Judaism, says that if someone attempts to kill you, kill them first. It makes no difference if it is a Zombie at all. However, if, in attempting to kill them, you could have stopped them from killing you by simply maiming them, and you didn’t just maim them—then it is tantamount to murder. In the case of Zombies one has no choice, since the maiming of them has little effect. Morally one must go for complete destruction.”

Zombies…Fast or Slow? Part 6

“Slow. There is something so terrifying about the slow attack that is inescapable. Serial killers can be fast, jaguars can be fast, a train about to hit you on the tracks can be fast—but there is a more nightmarish quality to the shambling corpse whose only goal is to find the nearest living human to eat. There is something incredibly horrible about the idea of being taken down by a slow, dumb predator—we expect the smart ones to get us, but not those relentless brainless ones.”—Doug Clegg, Bram Stoker Award-winning author of

“Slow. There is something so terrifying about the slow attack that is inescapable. Serial killers can be fast, jaguars can be fast, a train about to hit you on the tracks can be fast—but there is a more nightmarish quality to the shambling corpse whose only goal is to find the nearest living human to eat. There is something incredibly horrible about the idea of being taken down by a slow, dumb predator—we expect the smart ones to get us, but not those relentless brainless ones.”—Doug Clegg, Bram Stoker Award-winning author of

The Vampyricon “For me, slow, but I have no beef with the fast ones. But slow makes more sense. They’re inexorable, so why run? What’s the hurry?”—Novelist and comic book writer/artist Bob Fingerman

“For me, slow, but I have no beef with the fast ones. But slow makes more sense. They’re inexorable, so why run? What’s the hurry?”—Novelist and comic book writer/artist Bob Fingerman “Fast! (Unless they’re after my ass!)”—Best-selling mystery novelist Ken Bruen, author of

“Fast! (Unless they’re after my ass!)”—Best-selling mystery novelist Ken Bruen, author of

The Guards

and

American Skin

The Zombie Factor

In his excellent series of living dead novels, author Brian Keene takes a decidedly supernatural view and has a demonic force causing the dead to rise. Unlike many of the other zombie stories, Keene also has this otherworldly evil resurrect all recently dead things: animals, insects. It’s an attack on all life, not just on humanity, and as such is an unstoppable force.

Keene comments, “The zombies in

The Rising

9

and

City of the Dead

aren’t your father’s undead. These are not mindless, slow-moving corpses. They’re smart. Fast. And very, very hungry. They can hunt you, set traps for you. Use weapons. Drive cars. In the mythos I’ve created for both books (and indeed, all of my novels) the bodies of the dead are possessed by the Siqqusim, a race of demonic entities, led by an arch-demon named Ob. The Siqqusim have been with us for a long time. Their cults sprang up in Assyrian, Sumero-Akkadian, Mesopotamian, and Ugaritic cultures, where they were consulted by necromancers and soothsayers. Eventually, they were banished to a realm, which is neither Heaven nor Hell, but somewhere in between. Now, they have been unleashed upon the Earth once again. After we die, they take up residence in our bodies, specifically—in our brains. Once the body is destroyed, the Siqqusim return to the Void and await transference to a new body. The process begins anew. Finally, when they have destroyed all of the planet’s life forms, they move on to somewhere else, just like locusts, and start all over again. There are life forms on other planes of existence, other realities, and the Siqqusim have reign over them all.”

David Wellington works possession from a different angle in his zombie trilogy,

Monster Island, Monster Nation

, and

Monster Planet.

10

In that series of books an ancient evil force exerts its will to transform the world into a global kingdom of the dead. Of his choice to vary the model, Wellington says, “I wanted to do something different with my zombies. I didn’t want to say it was a virus, or a prion, or radiation from a Venusian space probe. I wanted to tell a story about the end of the world, too, which had to encompass all of human history, from the dawn of civilization until its final collapse.”

This is not to say that the more supernatural zombie stories veer completely away from science. In fact, Wellington nicely combines the two and has a doctor who stage-manages his own transition to the zombie state in order to retain his intelligence. The doctor (Gary), knowing that he was dying of the infection, keeps an oxygen mask on as his body dies so that his brain doesn’t suffer from the deteriorating effects of oxygen deprivation. This is a clever plot device that allows for the creation of a truly unique thinking zombie. “Gary’s original role,” Wellington says, “was simply to be an observer behind enemy lines—someone who could walk amongst the zombies and see what they did when there were no living people around. As I wrote the book however he evolved and became central to the thematic questions of the story—what is the real difference between life and undeath? And what kind of obligations last beyond death? Instead of creative freedom I think he gave the novel its direction.”