Zero (20 page)

Authors: Charles Seife

While retreating from Moscow, Napoleon's army was whittled down to almost nothing by a harsh winter and an equally harsh Russian army. At the battle of Krasnoy, Poncelet was left for dead on the battlefield. Still alive, he was captured by the Russians. Moldering in a Russian prison, Poncelet founded a new discipline: projective geometry.

Poncelet's mathematics was the culmination of the work begun by the artists and architects of the fifteenth century, like Filippo Brunelleschi and Leonardo da Vinci, who discovered how to draw realisticallyâin perspective. When “parallel” lines converge at the vanishing point in a painting, observers are tricked into believing that the lines never meet. Squares on the floor become trapezoids in a painting; everything gets gently distorted, but it looks perfectly natural to the viewer. This is the property of an infinitely distant pointâa zero at infinity.

Johannes Kepler, the man who discovered that planets travel in ellipses, took this ideaâthe infinitely distant pointâone step further. Ellipses have two centers, or

foci;

the more elongated the ellipse, the farther apart these foci are. And all ellipses have the same property: if you had a mirror in the shape of an ellipse and you placed a lightbulb at one focus, all the beams of light would converge at the other focus, no matter how stretched-out the ellipses are (Figure 29).

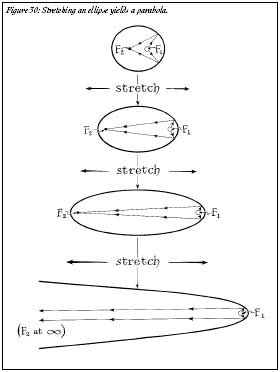

In his mind Kepler stretched an ellipse out more and more, dragging one focus farther and farther away. Then Kepler imagined that the second focus was infinitely far away: the second focus was a point at infinity. All of a sudden the ellipse becomes a parabola, and all of the lines that converged to a point become parallel lines. A parabola is simply an ellipse with one focus at infinity (Figure 30).

Figure 29: Light rays inside an ellipse

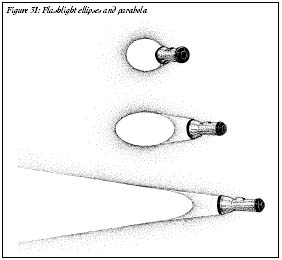

You can see this very nicely with a flashlight. Go into a dark room, stand next to a wall, and point the flashlight directly at it. You will get a nice, round circle of light projected on the wall. Now slowly tilt the flashlight upward (Figure 31). You'll see the circle stretch out into an ellipse that gets longer and longer as you increase the tilt. All of a sudden, the ellipse opens up and becomes a parabola. Thus, Kepler's point at infinity proved that parabolas and ellipses are actually the same thing. This was the beginning of the discipline of projective geometry, where mathematicians look at the shadows and projections of geometric figures to uncover hidden truths even more powerful than the equivalence of parabolas and ellipses. However, it all depended upon accepting a point at infinity.

Figure 30: Stretching an ellipse yields a parabola.

Figure 31: Flashlight ellipses and parabola

Gérard Desargues, a seventeenth-century French architect, was one of the early pioneers of projective geometry. He used the point at infinity to prove a number of important new theorems, but Desargues's colleagues couldn't understand his terminology and concluded that Desargues was nuts. Though a few mathematicians, like Blaise Pascal, picked up on Desargues's work, it was forgotten.

None of this mattered to Jean-Victor Poncelet. As Monge's student, Poncelet had learned the technique of projecting diagrams onto two planes, and as a prisoner of war he had a lot of spare time on his hands. He used his stay in prison to reinvent the concept of a point at infinity, and combining it with Monge's work, he became the first true projective geometer. Upon his return from Russia (carrying a Russian abacus, by then an archaic oddity) he raised the discipline to a high art.

*

However, Poncelet had no idea that projective geometry would reveal the mysterious nature of zero, because the second important advance, the complex plane, was still needed. We must turn to Germany for this piece of the puzzle.

Carl Friedrich Gauss, born in 1777, was a German prodigy, and he began his mathematical career with an investigation of imaginary numbers. His doctoral thesis was a proof of the fundamental theorem of algebraâproving that a polynomial of degree

n

(a quadratic has degree 2, a cubic has degree 3, a quartic has degree 4, and so on) has

n

roots. This is only true if you accept imaginary numbers as well as real numbers.

Throughout his life Gauss worked on an incredible variety of topicsâhis work on curvature would become a key component of Einstein's general theory of relativityâbut it was Gauss's way of graphing complex numbers that revealed a whole new structure in mathematics.

In the 1830s Gauss realized that each complex numberânumbers that have real and imaginary parts, like 1 - 2

i

âcan be displayed on a Cartesian grid. The horizontal axis represents the real part of the complex number, while the vertical axis represents the imaginary part (Figure 32). This simple construction, called the complex plane, revealed a lot about the way numbers work. Take, for example, the number

i.

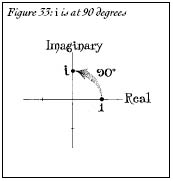

The angle between

i

and the

x

-axis is 90 degrees (Figure 33). What happens when you square

i

? Well, by definition,

i

2

=-1âa point whose angle is 180 degrees from the

x

-axis; the angle has doubled. The number

i

3

is equal to -

i

â270 degrees from the

x

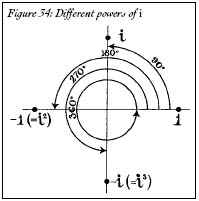

-axis; the angle has tripled. The number

i

4

= 1; we have gone around 360 degreesâexactly four times the original angle (Figure 34). This is not a coincidence. Take any complex number and measure its angle. Raising a number to the

n

th power multiplies its angle by

n.

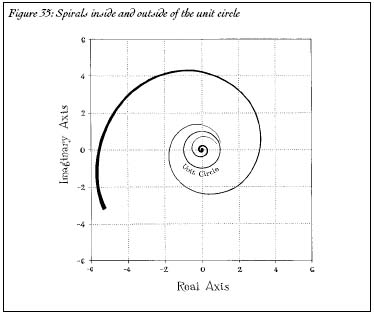

And as you keep raising the number to higher and higher powers, the number will spiral inward or outward, depending on whether the number is on the inside or on the outside of the unit circle, a circle centered at the origin with radius 1 (Figure 35). Multiplication and exponentiation in the complex plane became geometric ideas; you could actually see them happening. This was the second big advance.

Figure 32: The complex plane

Figure 33:

i

is at 90 degrees

Figure 34: Different powers of

i

The person who combined these two ideas was a student of Gauss's: Georg Friedrich Bernhard Riemann. Riemann merged projective geometry with the complex numbers, and all of a sudden lines became circles, circles became lines, and zero and infinity became the poles on a globe full of numbers.

Figure 35: Spirals inside and outside of the unit circle

Riemann imagined a translucent ball sitting atop the complex plane, with the south pole of the ball touching zero. If there were a tiny light at the north pole of the ball, any figures that are marked on the ball would cast shadows on the plane below. The shadow of the equator would be a circle around the origin. The shadow of the southern hemisphere is inside the circle and the shadow of the northern hemisphere is outside (Figure 36). The originâzeroâcorresponds to the south pole. Every point on the ball has a shadow on the complex plane; in a sense, every point on the ball is equivalent to its shadow on the plane and vice versa. Every circle on the plane is the shadow of a circle on the ball, and a circle on the ball corresponds to a circle on the planeâ¦with one exception.