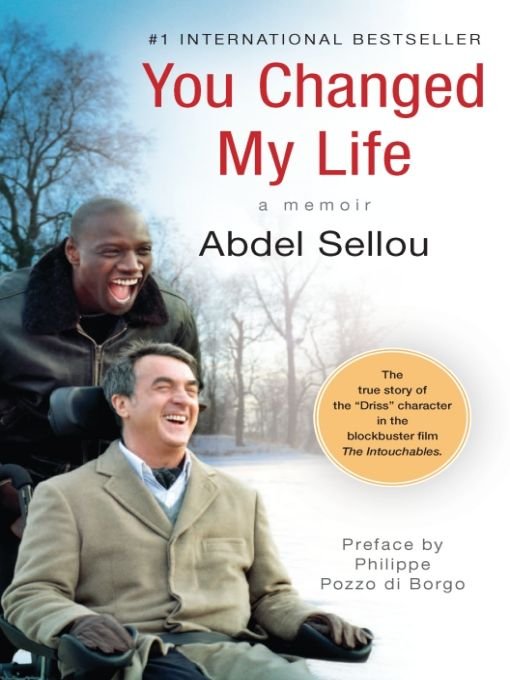

You Changed My Life

Read You Changed My Life Online

Authors: Abdel Sellou

Table of Contents

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

Â

For Philippe Pozzo di Borgo,

For Amal,

For my children, who will find their own way

For Amal,

For my children, who will find their own way

Preface

When Ãric Tolédano and Olivier Nakache were writing the

script for the hit French film

Intouchables,

they wanted to interview my special friend Abdel Sellou. He answered: “Ask Pozzo, I trust him.” When I was writing the new edition of my memoir,

Le Second

Souffle,

Suivi par Le Diable Gardien

(“Second Wind, followed by Guardian Demon”), I asked Abdel to help me remember a few of our shared adventures, but he also declined. Abdel doesn't talk about himself. He acts.

script for the hit French film

Intouchables,

they wanted to interview my special friend Abdel Sellou. He answered: “Ask Pozzo, I trust him.” When I was writing the new edition of my memoir,

Le Second

Souffle,

Suivi par Le Diable Gardien

(“Second Wind, followed by Guardian Demon”), I asked Abdel to help me remember a few of our shared adventures, but he also declined. Abdel doesn't talk about himself. He acts.

With incredible energy, generosity and impertinence, he was by my side for ten years. And in that time he supported me through each painful phase of my existence. First, he helped me with my wife, Béatrice, who was dying, then he pulled me out of the depression that followed her death. He basically helped me find the desire to live again . . .

Throughout the course of these years we've had many things in common: never revisiting the past, never projecting ourselves in the future, and most important, living, or surviving,

in the moment. The suffering that was consuming me destroys memory; Abdel didn't want to look back on a youth that I could only guess was turbulent. We were both worn clean of any memory. During all of that time, I only got a few snippets of his story that he was willing to reveal to me. I have always respected his reserve. He quickly became a part of the family, but I have never met his parents.

in the moment. The suffering that was consuming me destroys memory; Abdel didn't want to look back on a youth that I could only guess was turbulent. We were both worn clean of any memory. During all of that time, I only got a few snippets of his story that he was willing to reveal to me. I have always respected his reserve. He quickly became a part of the family, but I have never met his parents.

In 2003, Abdel and I and our unusual relationship were featured on an episode of Mireille Dumas's French television program

Vie privée, vie publique

(“Private Life, Public Life”). Later Mireille decided to make a one-hour documentary about our adventure, which was broadcast as

à la vie, à la mort

(meaning, roughly, “Come what may”). Two journalists followed us for several weeks. Abdel let them know, in no uncertain terms, that probing anyone from his entourage about his past was out of the question. However, they didn't respect his wishes, and as a result, were subjected to an impressive fit of rage. Not only did Abdel not want to talk about himselfâhe didn't want others to talk about him either!

Vie privée, vie publique

(“Private Life, Public Life”). Later Mireille decided to make a one-hour documentary about our adventure, which was broadcast as

à la vie, à la mort

(meaning, roughly, “Come what may”). Two journalists followed us for several weeks. Abdel let them know, in no uncertain terms, that probing anyone from his entourage about his past was out of the question. However, they didn't respect his wishes, and as a result, were subjected to an impressive fit of rage. Not only did Abdel not want to talk about himselfâhe didn't want others to talk about him either!

Everything seemed to change last year. What a surprise it was to hear him answering, with genuine sincerity, all the questions asked by Mathieu Vadepied, the artistic director who filmed the bonus feature for the

Intouchables

DVD. I learned more about him during the three days spent together in my home in Essaouira, Morocco, than I had in our fifteen-year friendship. He was ready to tell his story, all of it, from before, during, and after our meeting.

Intouchables

DVD. I learned more about him during the three days spent together in my home in Essaouira, Morocco, than I had in our fifteen-year friendship. He was ready to tell his story, all of it, from before, during, and after our meeting.

What an accomplishment to come from the silence of his twenties to the pleasure he gets today in recounting his escapades and sharing his thoughts! Abdel, you will never cease

to amaze me . . . What a pleasure to read

You Changed My Life

. In it, I recognize Abdel's humor, his sense of provocation, his thirst for life, his kindness, and now, his wisdom.

to amaze me . . . What a pleasure to read

You Changed My Life

. In it, I recognize Abdel's humor, his sense of provocation, his thirst for life, his kindness, and now, his wisdom.

According to the title of his book, I have changed his life . . . That may be true, but in any case, what I

am

certain of is that he changed mine. I will say it again: he supported me after Béatrice's death and helped me find the desire to live again with joyful determination and rare emotional intelligence.

am

certain of is that he changed mine. I will say it again: he supported me after Béatrice's death and helped me find the desire to live again with joyful determination and rare emotional intelligence.

And then one day, he took me to Morocco . . . where he met his wife, Amal, and where I met my companion, Khadija. Since then, we see each other with our children regularly. The “Untouchables” have become the “Uncles.”

Philippe Pozzo di Borgo

Prelude

I ran as fast as I could. I was in good shape back then. The

chase started on the rue de la Grande TruanderieâBig Cheat Street. You can't make that stuff up. With two friends, I had just relieved some rich kid of a slightly outdated Sony Walkman. I was going to explain to him how we'd actually done him a favor, since, as soon as he got home, his daddy would rush right out and buy him the latest model with better sound, easier functions, longer battery life . . . but I didn't have the time.

chase started on the rue de la Grande TruanderieâBig Cheat Street. You can't make that stuff up. With two friends, I had just relieved some rich kid of a slightly outdated Sony Walkman. I was going to explain to him how we'd actually done him a favor, since, as soon as he got home, his daddy would rush right out and buy him the latest model with better sound, easier functions, longer battery life . . . but I didn't have the time.

“Code twenty-two!” yelled a voice.

“Don't move!” shouted another.

We took off.

Flying down rue Pierre-Lescot, I slalomed between passersby with impressive agility. It was easyâclassy, really. Like Cary Grant in

North by Northwest.

Or like that ferret in the children's song, only bigger: he went this way, he went that way . . . Turning right onto rue Berger, I was planning to disappear into

Les Halles. Bad ideaâtoo many people blocking the stair entrance, so I cut a hard left onto rue des Bourdonnais. The rain had made the pavement slick and I wasn't sure who had better solesâme or the cops. Luckily, mine didn't let me down. I was like Speedy Gonzales racing at high speed, chased by two mean Sylvesters, ready to gobble me up. I really hoped this would end like in the cartoon. Now on the Quai de la Mégisserie, I caught up with one of my buddies who'd taken off a split second before me and was a much better sprinter. I raced behind him onto the Pont Neuf, closing the distance between us. The shouts from the cops were growing fainter behind usâit seemed like they were already giving up. Of course they wereâwe were the heroes . . . still, I didn't risk looking back to check.

North by Northwest.

Or like that ferret in the children's song, only bigger: he went this way, he went that way . . . Turning right onto rue Berger, I was planning to disappear into

Les Halles. Bad ideaâtoo many people blocking the stair entrance, so I cut a hard left onto rue des Bourdonnais. The rain had made the pavement slick and I wasn't sure who had better solesâme or the cops. Luckily, mine didn't let me down. I was like Speedy Gonzales racing at high speed, chased by two mean Sylvesters, ready to gobble me up. I really hoped this would end like in the cartoon. Now on the Quai de la Mégisserie, I caught up with one of my buddies who'd taken off a split second before me and was a much better sprinter. I raced behind him onto the Pont Neuf, closing the distance between us. The shouts from the cops were growing fainter behind usâit seemed like they were already giving up. Of course they wereâwe were the heroes . . . still, I didn't risk looking back to check.

I ran as fast as I could, until I was almost out of breath. My feet were killing me so badly I didn't think I could keep it up all the way to Denfert-Rochereau station. To cut it short, I hopped over the short wall meant to keep pedestrians from falling into the river. I knew there was about a twenty-inch ledge on the other side that I'd be able to walk along. Twenty inches was enough for me. I was slim back then. I crouched, looking at the muddy waters of the Seine rushing powerfully toward the Pont des Artsâthe pounding of the cops' cheap shoes on the pavement getting louderâand held my breath, hoping the noise would reach its climax, continue on and fade away. Completely oblivious to the danger, I wasn't afraid of falling. I had no idea where my two friends had gone, but I trusted them to find a good hiding place. As the cops ran past, I snorted

oink oink,

snickering into the collar of my sweatshirt. A barge shot out from under me and I almost jumped from the

shock. I stayed there a minute to catch my breath. I was thirsty. I would have loved a Coke about then.

oink oink,

snickering into the collar of my sweatshirt. A barge shot out from under me and I almost jumped from the

shock. I stayed there a minute to catch my breath. I was thirsty. I would have loved a Coke about then.

I wasn't a hero. I knew that already, but I was fifteen and had always lived like a wild animal. If I'd had to talk about myself, define myself in complete sentences with adjectives, names, and all the grammar they'd tried to hammer into me at school, I would have had a hard time. Not because I didn't know how to express myselfâI was always good at talkingâbut because I'd have had to stop and think. Look in a mirror and shut up for a minuteâsomething that's tough for me even now at fortyâand wait for something to come to me. An idea, my own self-appraisal, which, if it were an honest one, would have been uncomfortable. Why would I put myself through that? No one was asking me to, not at home or at school. Incidentally, I was great at handling interrogation. If someone even thought of asking me a question, I took off without blinking. As a teen, I ran fast; I had good legs and the best reasons for running.

Every day, I was on the street. Every day, I gave the cops a new reason to come after me. Every day, I sped from one neighborhood of the city to the next, like in some fantastic theme park where anything goes. The object of the game: take as much as possible without getting caught. I needed nothing. I wanted everything. I was growing up in a giant department store where everything was free. If there were any rules, I wasn't aware of them. No one told me about them when they could have, and after that, I didn't give them the chance. That suited me just fine.

One October day in 1997, I was run over by an eighteen-wheeler. The result: a fractured hip, smashed left leg, intensive surgery, and weeks of rehabilitation in the suburb of Garches. I stopped running and started gaining a little weight. Three years before that, I'd met a man stuck in a wheelchair after a paragliding accidentâPhilippe Pozzo di Borgo. For a short time, we were equals.

Invalides

âinvalids. As a kid, that word only meant a metro station to me, an esplanade wide enough to steal stuff while keeping an eye on the guys in uniformâan ideal playground. I had been benched temporarily, but Pozzo was permanently out of the game. Last year we both became the heroes of a hit film,

Intouchables

. Now suddenly everyone wants to touch us! The thing is, even I'm a good guy in the story. I have perfectly straight teeth, I smile all of the time, have a spontaneous laugh, and I bravely care for the guy in the wheelchair. And I dance like a god. Everything the two characters do in the filmâthe high-speed freeway chase in a luxury sports car, the paragliding, the nighttime walks through ParisâPozzo and I really lived it. I didn't do that much for himâat least not as much as he did for me. I pushed him around, acted as his companion, eased his pain as much as possible, and I was present.

Invalides

âinvalids. As a kid, that word only meant a metro station to me, an esplanade wide enough to steal stuff while keeping an eye on the guys in uniformâan ideal playground. I had been benched temporarily, but Pozzo was permanently out of the game. Last year we both became the heroes of a hit film,

Intouchables

. Now suddenly everyone wants to touch us! The thing is, even I'm a good guy in the story. I have perfectly straight teeth, I smile all of the time, have a spontaneous laugh, and I bravely care for the guy in the wheelchair. And I dance like a god. Everything the two characters do in the filmâthe high-speed freeway chase in a luxury sports car, the paragliding, the nighttime walks through ParisâPozzo and I really lived it. I didn't do that much for himâat least not as much as he did for me. I pushed him around, acted as his companion, eased his pain as much as possible, and I was present.

Other books

Forbidden Lord by Helen Dickson

The Vitalis Chronicles: Tomb of the Relequim by Swanson, Jay

Ever Tempted by Odessa Gillespie Black

Find Me (Life After the Outbreak, Book 2) by Baker, LJ

The Angelus Guns by Max Gladstone

The Chimp and the River: How AIDS Emerged from an African Forest by David Quammen

Aftermath by Peter Turnbull

Don't Cry by Beverly Barton

Edith Wharton - Novella 01 by Fast (and) Loose (v2.1)

American Uprising by Daniel Rasmussen