Yoga for a Healthy Lower Back (40 page)

Read Yoga for a Healthy Lower Back Online

Authors: Liz Owen

There's another dynamic that has almost the opposite effect on the shape of the lumbar spine, yet it can cause thoracic and neck issues similar to those that excessive lordosis causes in the lower back. In our new, equally pain-inducing scenario, tight hamstring muscles pull on the sit bones, tipping the pelvis backward and flattening the normal curve of the lumbar spine. And even though it's important to strengthen your abdominal core to support a natural curve in your lower back, an overly strong or tight abdominal core may also contribute to a flattened lower back.

6

A flattened lower back doesn't have the same structural stability as a lower back in its natural curve because the muscles weaken as they flatten out. A lower back in this condition will more easily overround backward in a forward-bending position. The thoracic spine then overworks to compensate for the instability of the lumbar spine, which results, again, in the musculature tightening up and contracting while the neck and head shift forward. In another response to a flattened lower back, the entire spine can flatten out. In this case all the myofascia weakens, creating vulnerability in the vertebrae and spinal disks from the sacrum all the way up to the cervical spine.

In all these scenarios, there's imbalance and tightness throughout the spine, from the base of your lower back up to the top of your neck. These

shifts can happen almost imperceptibly and over a long period of time. By the time you feel lower back or thoracic pain, the shift in your musculature has become well set, and you have significant work to do to reshape it.

Fortunately, though, muscles love to stretch and “breathe.” One of the great joys of being a yoga teacher is watching a student's tight back change its shape through yoga practice. I've watched as students' upper torso and back muscles elongate and become toned. It's as if someone opened the windows into a student's chest, letting in soft breezes to slowly and gently rinse away imbalances and tension.

Anatomy of the Upper Back

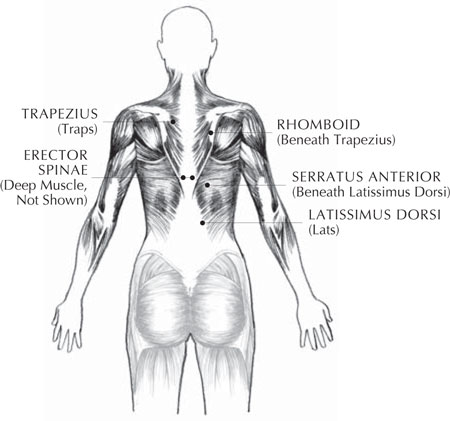

Before we move ahead, and because this is an area of the body we haven't explored, let's take a brief trip through five of the major muscle groups of your upper back: the “lats,” “traps,” rhomboids, serratus, and erectors (

illustration 18

). Their tone has an important role to play in your journey into wellness:

â¢Â Â

Latissimus dorsi:

You first encountered these muscles, typically called the “lats,” in chapter 4 because they straddle the thoracic and lumbar spines. They are the largest upper back muscles, and they are responsible for stabilizing the spine in back-bending and forward-bending movements, as well as adduction (moving toward the body), internal rotation (turning inward), and the extension of the shoulder joint back and away from the front of the body. The lats start at the lower thoracic spine, right above the top of your lumbar spine and at the top of the back hip bones. They wrap around and up the sides of the body, where they interact with the oblique abdominal muscles and help with spinal stability, and then they attach to the inside of your upper arm bones.

7

I'm sure I only need to mention the name of swimmer Michael Phelps, who holds the all-time record for the most Olympic gold medals, for you to visualize well-developed lats.

8

â¢Â Â

Trapezius:

The “traps” are the large muscles that lie on either side of the upper spine, forming a large V-shape. They start at the base of your thoracic spine at T12, spread out and up along your back, and attach to your shoulder blades and the base of the skull bone at a point called the occiput. When you engage the lower traps, at your middle back, your shoulder blades are drawn down and away from your neck, an action called “depression.” This simple action has a ripple effect: It elongates the neck muscles, especially in a back-bending position, which allows the head to shift into alignment over the shoulders; it encourages the shoulders to draw back, and it broadens your upper chest.

Illustration 18. The Muscles of the Upper Back

The intermediate traps work with the rhomboids to draw the shoulder blades together, a movement called “retraction.” I'd like you to feel how these two actions, depression and retraction, work together to create support for your upper chest. First, using your lower traps, “depress” your shoulder blades down and away from your neck. Find your intermediate traps by “retracting” your shoulder blades toward your spine. Now visualize your shoulder blades as “helping hands” easing your shoulders into alignment from behind and creating support for your upper chest as they gently “hug” your upper back.

The upper traps lift the shoulder blades up. You can find your upper traps simply by lifting your shoulders up toward your ears, a movement called “elevation.”

â¢Â Â

Rhomboids:

These muscles attach your spine to your shoulder blades and work with the intermediate traps to retract your shoulder blades. When poor postural habits cause the shoulder blades to slide away from the spine, the rhomboids first become overstretched and weak, and then tight and rigid. Upper back pain due to weak and tight rhomboids can be felt as chronic achiness or sharp pain along the edges of the shoulder blades.

9

â¢Â Â

Serratus anteriors:

These muscles work reciprocally with the rhomboidsâthey pull the shoulder blades away from the spine. Shortened serratus muscles draw the shoulder blades out to the outer back rib cage, straining and weakening the rhomboids. When a

person has both a tight serratus and strained rhomboids, it's a good bet they also have an exaggerated kyphotic thoracic spine.

10

â¢Â Â

Erector spinae:

You also first explored this group of long, complex muscles in

chapter 4

. Your “erectors” have many jobs; they bring your spine into forward bending (flexion) and back bending (extension), and, possibly most importantly, they also hold your spine in an upright position. They begin all the way down in the layers of the lower back fascia and climb up your spine, connecting with each vertebra, all the way to the base of the skull (occiput). The outer layers of the erector spinae group are long and strappy-lookingâthese are the muscles that become thick, short, and very prominent in a lower back with an exaggerated lordosis. They become spread out and weakened (and achy!) in an upper back with an exaggerated kyphosis. The deeper layers of the erector spinae muscles connect vertebrae to each other, forming a pattern that resembles a long braid as they weave their way up from the sacrum to the occiput.

11

YOUR UPPER BACK IS PRIMED AND READY

Although our work so far has focused on the lower back, many of the poses you've practiced also strengthen and tone your middle and upper back musculature. So you're primed and ready for the poses to come in this chapter! Revisit the following poses for an

aha!

moment on how they recruit your middle and upper back:

â¢Â  Bridge Pose

â¢Â  One-Legged Bridge Pose

â¢Â  Noble Warrior Pose

â¢Â  Side Angle Pose

â¢Â  Triangle Pose

â¢Â  Table-Balance Pose

â¢Â  Supported Cobra Pose

â¢Â  Supported Locust Pose

â¢Â  Flowing Bridge Pose

â¢Â  Flying Locust Pose

â¢Â  Swimming Locust Pose

â¢Â  Cobra Pose Flow

Anatomy of the Neck

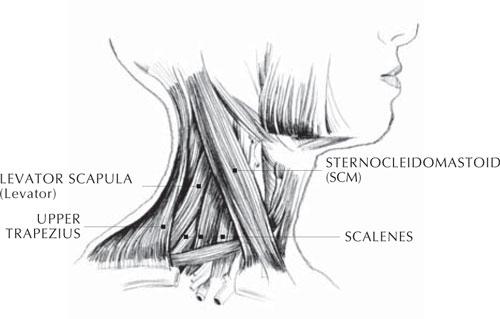

Not to worry, you won't be tested on all of these muscle names! But as you prepare to practice the poses in this chapter, it will be helpful to understand a little about the major muscles in your neck. The full list of muscles that allow the head and the neck to move can sound intimidating, yet when you read their names, with their repeated use of the Latin words for “long,” “upright,” and “head,” you understand the function of these musclesâto maintain the long and upright spine we've worked on throughout this book and, of course, to support your head on top of your spine. Instead of overwhelming you with the whole kit and caboodle, I've chosen four major neck muscle groups I think you'll relate to easily (

illustration 19

):

â¢Â Â

Sternocleidomastoids:

Commonly abbreviated as the SCMs, these muscles are recognizable as the long, thick muscles in the outer layers of the front of the neck that run angularly up from the breastbone and collarbones to the sides of the temporal bones (the bones at the side and base of your skull). They attach to the skull right behind your ears. The SCM muscles assist with cervical and upper spine flexion, as in an abdominal crunch, in

Chin Locks

, and with all aspects of head movement.

12

If you press your hand against your forehead and push into it with your head, you will feel your SCM muscles contract. Perhaps you've seen a person whose head is forward, whose chin is lifted, and whose back neck is shortened . . . perhaps you've experienced this postural misalignment yourself. This is the very challenging result of tightness in the SCM muscles.

13

â¢Â Â

Scalenes:

This muscle group is actually three pairs of muscles in the sides of the neck. They originate from cervical vertebrae C2 to C7 and they extend down through the neck to where they attach at your first and second ribs. The scalenes are responsible for side flexion of the neck, and they lift the first and second ribs. When you tilt your head back and flex your neck toward your right shoulder, you will feel your left scalenes stretching.

14

â¢Â Â

Levator scapulae:

The “levators” run along the back and sides of the neck from cervical vertebrae C1 to C4 down to the inner upper edges of the shoulder blades, the place where tension commonly settles into the upper back. You can easily find this point by swinging one arm around the front of your chest to the opposite shoulder as if patting yourself on the back. Your fingers will land on or very near the inner upper edge of the shoulder blade. Shift your fingers slightly toward your spine and you'll find the spot. You're feeling the traps, with the levators underneath. If you massage them, you may feel some tenderness there . . . and maybe you'll release some tension in the process! Just as their name sounds, their main function is to elevate (lift) your shoulder blades.

15

Illustration 19. The Muscles of the Neck (Side View)

Illustration 20. The Muscles of the Neck (Back View)

Tightness and shortness in the scalenes and levators are usually caused by the subtle tensions that slip deep into the shoulders over time, whether from hunching over a computer, slouching against the wind on a cold winter's day, or struggling with underlying life pressures and stress. Trauma or injury can cause a startle response that shortens the musculature of the front of the body and pulls the shoulders up toward the ears and forward, creating the same tightness and shortness in these muscles. Stretching the muscles with yoga postures will help to release tension and drop the shoulders away from the ears.

â¢Â Â

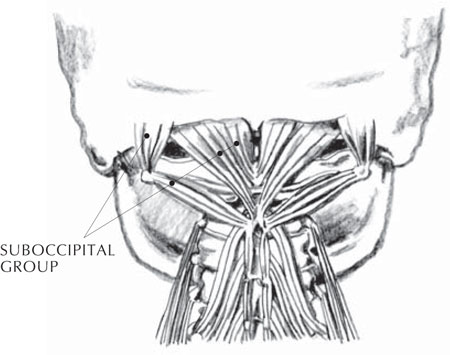

Suboccipital group:

This is a group of short, deep muscles that connect the back base of the skull to the top of the cervical spine (

illustration 20

). Sometimes it's called the suboccipital “star,” which is exactly what the muscles look like when viewed from behind. They radiate up and out to the base of the skull from the star's center at cervical vertebrae C1 and C2. The suboccipitals, as well as the scalenes, are limited in their movement and can prevent the SCMs from releasing tension, because they may reach their limitation long before the superficial SCM is brought into a stretch.

16

To find your suboccipitals, massage the “valleys” just below the base of your skull at the back with your thumbs until your thumbs go beyond the outer layers of muscles and find the deeper muscles under the occipital ridge (the bottom edge of the occipital bone). Now, here's an amazing feeling: Keeping your head still, move your eyes right and left and up and down, and you will feel your suboccipitals move. According to Thomas W. Myers in his book

Anatomy Trains,

these muscular and eye movements are so fundamentally connected that any eye movement will produce a change in tone in the suboccipitals. From there, “the rest of the spinal muscles âlisten' to the suboccipitals and tend to organize by following their lead.” Myers literally means “the rest of the spinal muscles”âall of them. He says, “Loosening the neck is often key to intransigent problems between the shoulder blades, in the lower back, and even in the hips.”

17