Year of the King: An Actor's Diary and Sketchbook - Twentieth Anniversary Edition (24 page)

Read Year of the King: An Actor's Diary and Sketchbook - Twentieth Anniversary Edition Online

Authors: Antony Sher

Tags: #Arts & Photography, #Performing Arts, #Theater, #Acting & Auditioning, #Stagecraft, #Biographies & Memoirs, #Arts & Literature, #Entertainers, #Humor & Entertainment, #Literature & Fiction, #Drama, #British & Irish, #World Literature, #British, #Shakespeare

Making Richard sexy seems to me the same as making him funny; it

avoids the issue, avoids the pain.

CONFERENCE HALL Our rehearsal room used to be hired out for

conferences to the citizens of Stratford. One wall belonged to the original

Memorial Theatre and survived the Great Fire in 1926. It is a beautiful

room full of old things from old productions: a goblet, a sceptre, a throne.

Theatre props age faster than their real counterparts. The cardboard

shows, the plaster shows, they look crude and childish, reminding you of

school productions.

There's an old wind machine on the shelf above the door, there's a

sword rack, there's a horse you strap round your middle and jog into

battle with. It's full of ghosts - one of them sits on an upper level looking

down, a white polystyrene figure from some long-forgotten show, sitting intently forward, elbows on knees, keeping a watchful eye on this latest

production. The Ghost of R S C Past.

It is the perfect rehearsal space, miles high, full of light and air. On the

ceiling giant circular skylights; one sends a shaft of sun on to our table as

individual members of the cast come in one by one to read their scenes.

The light is soft but clear; it illuminates these new faces.

Roger Allam (Clarence) in beret and granny sunglasses, looking like a

jazz musician.

Brian Blessed (Hastings) a small mountain, teeth he could hang from

a trapeze with, a chuckling squeeze-box voice: `Such an exciting project,

so thrilled, Tony how d'you do, so pleased to meet you, Michael Gambon

tells me you're hell to work with ... Charles! Are you stage-managing?

Charles is a sweetie, lousy in bed but what a cook!'

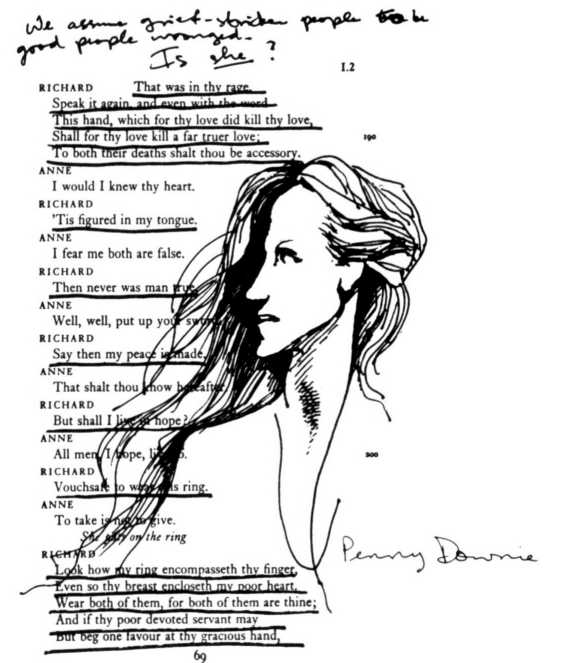

Penny Downie (Lady Anne), Australian accent when she isn't reading,

striking classical profile, long blonde hair. Instant rapport - we look one

another in the eye as we read. Whatever Richard's own sex appeal may

or may not be, the sexuality in the scene is undeniable. The in-and-out

rhythm of their last exchange.

Finally Frances Tomelty (Queen Elizabeth), eyes like black coals, a

mane of hair, two miniature silver spoons for ear-rings. At one point Bill

compares Richard to Macbeth - she instantly crosses herself.

I say, `I don't think that superstition applies if you're just rehearsing.'

`It's not a superstition to me,' she says, `I've lived through it.'

Of course - she was Lady Macbeth in the O'Toole production.

The theatre is buzzing with excitement after last night's visit by Prince

Charles and Princess Di to Henry V. They were Ken Branagh's personal

guests and apparently had requested that their visit be unofficial. They

said they would just slip in. How the two most famous people in the world

thought they could just slip in to a busy public place is a puzzle. Inevitably,

by the interval a crowd had gathered in the front of the stalls, staring up

at the dress circle where they were sitting. The second half couldn't start

for some time because the audience was pointing in the wrong direction.

Afterwards, Branagh went to meet them and Prince Charles apologised

for upstaging the show.

Awake early again. The text for this morning's thought is `lump of foul

deformity'. After only two days' work on the text I've become less interested

in the physical shape, and more in Richard's mind, his intelligence and

cunning. I now feel encumbered by the monster image. But we are being

pressurised to make up our minds - the wardrobe staff can't begin to

make my costumes until the exact measurements of the deformity are

settled. This seems to be putting the cart before the horse. Ideally, I would

like several weeks working just on the text, then a couple of weeks

experimenting with shapes and movements, and only then should we

decide what he's going to look like. Of course that's impossible with the

theatre system in this country. For instance Bill D.'s set designs had to

be in by February. And however exciting they might look, they closed all

other options long before rehearsals - and the real exploration of the play

- had even started.

FIRST S C E N E Up until now we've been sitting round the table reading

and discussing the text. Today we venture out on to the rehearsal floor.

Pleased that my early idea about the harmless cripple sitting in the sun

seems to work. I position myself over at the proscenium arch, very much

on the sidelines, calling out and reaching for Clarence and Hastings as

they pass, as if to say, `Forgive me, it's so much trouble to get up.' Then at the end of the Hastings episode, my line `Go you before and I will

follow you' becomes `Oh please don't wait for me, I take hours.' Richard

exploits his disability to lag behind, to plot and chat to the audience.

Both Roger and Brian seem to be terrible corpsers like me, so rapport

is quickly established.

Lots of hump jokes already. Roger goes to pat my shoulder, remembers

the hump, and asks, `Uhm, which side will you be dressing, Sir?'

LADY ANNE SCENE (Act 1, Scene ii) Penny has never seen the play or

even the film, which is a terrific advantage. Bill says to her, `We associate

grief with goodness. Grieving people get our sympathy, we automatically

assume them to be good people wronged. This is not necessarily so.' He

wants her cursing in the scene to be `a perverted form of praying, calling

on an avenging God'.

He has a brilliant idea for the beginning of the scene. The procession

with the corpse is illegal, not a state funeral as it is often played (Richard

has murdered Henry VI after all). So Bill wants the pallbearers and guards

to be nervous and edgy, eager to get it over with. Lady Anne, high on

grief, does the famous `Set down' speech as a deliberate piece of street

theatre. A little crowd forms - people already in the church either praying

or screwing among the tombs. Richard is just one of the crowd. At the

given moment he steps forward and so the wooing begins.

Before Penny leaves the rehearsal we show her Bill D.'s designs for

Richard. I say, `Given that you have to be seduced by him, how important

is it to you what he looks like?' Penny stares at the drawings open-mouthed

- she is the first of the cast to see our idea for Richard's image - and

finally she says, `I'll have to think about it.'

SO L U s I tell Bill how the whole monster/crutches image seems like an

imposition now. He seems a little thrown by this, says, `Well, we must try

it. We can't just abandon it.' We agree to set aside a session to experiment,

to try it in action. I will have to learn the first speech over the weekend

so that I'll have my hands free to use the crutches. And wardrobe will

make a rough of the deformity we've discussed, for me to wear.

An excellent session, discussing Richard's soliloquies. Then, we

discuss how to start the play. I describe the sequence from the Dwoskin

film - starting the speech in darkness, slowly limping into a pool of light.

Bill's idea is for the lights to discover Richard already there, but static. `If

we use the crutches -' Bill prefaces this carefully - `I want to save the surprise of them for as long as possible.' He asks me to experiment sitting

on them like a shooting stick. So the audience would think that was the

shape: an armless lump. Then on, `But I, that am not shap'd for sportive

tricks', whip out the crutches from behind and charge down stage. They

do work terrifically well for a trundling bull-like charge.

We discuss another idea I've had, about the seeds of Richard's megalomania. Actually the notion comes from what Monty was teaching: learning

to like yourself - in Richard's case it becomes a love affair. He begins the

play full of self-loathing ('Deformed, unfinished ... half made up'), then

after the wooing of Lady Anne there is a burgeoning narcissism ('I do

mistake my person all this while!').

Bill rejects this. He feels that it's too early in the play for such a radical

change of character.

THE DIRTY D U C K Bill and I are having supper when Pam dances up

to our table, a kind of Hawaiian dance with the little fingers of each hand

turned upwards. She tells us, `There are great expectations for the fruits

of your partnership.' She knows more about what's happening in the

RSC than anyone who works there. All of company life passes through

The Dirty Duck. But her discretion is legendary and she prides herself

on it.

She tells us about the pub. It was originally called The Black Swan.

She says no one knows when or why it was changed. Some old-timers

think it got nicknamed by Australian soldiers during the war, because

down-under black swans are known as `mucky ducks'. At the moment the

pub sign outside bears both names, one on either side.

She asks what time Richard 111 will finish; this crucially affects her trade.

`Hopefully before eleven,' says Bill, looking shifty. The touchy question

of cuts again. When Pam goes, he says grumpily, `I didn't realise, along

with all the other artistic considerations, drinking time had to be allowed

for as well.'

I am still reeling from shock. `Hopefully before eleven' means three and

a half hours. He says that he wants cuts to occur naturally as we rehearse

scenes, for the cast to volunteer them, not for him to impose them.

I say, `I'm sorry, that is not a good idea. Nobody other than me is going

to volunteer cuts. All the other parts are too compact already. It is always

much less painful for a cast to have the cuts from the start. What you

never have, you don't miss.'

`I know. Don't lecture me.'

This is said lightly, but startles me. Now that I think about it, I have

noticed a new edge in our relationship since Wednesday, probably because

we're both tense about the enormous task ahead. Earlier this evening I

had been arguing for Richard's throne to be carried. It seems to me that

if you are King and happen to be crippled, you don't walk, you get carried.

I delivered what, I suppose, was a little `lecture' on how we have to create

the paraphernalia of dictatorship, a display of megalomania. Bill suddenly

said, `Yes, I have grasped that he didn't want to be King for the bookkeeping!'

But eventually he did agree to the throne-carrying and actually that led

to a happy solution of the horse problem: they've decided against real

horses because of the unpredictability of their bowels, and instead are

going to create the image with horses' armour. The problem was how to

get these monstrous skeletons on and off. Alison Sutcliffe suggested

ritualising it even more and carrying the horses like the throne, with poles

through the sides, and so continuing that image.

Lie in bed wondering about the opening speech, how to combine charm

(which Bill feels is vital to the part) and pain (which I feel is necessary).

One solution would be to do it like the M C from Cabaret, a vulgar, circus

presentation of his deformity: `Deformed!' ... drum roll . . . `Unfinished!'

... cymbal crash ... But the idea is too Adrian Noble-ish, and smacks

of the Rustavelli version too. Another way would be to do it very Brechtian:

come on completely normally and strap on the pieces of deformity as I

describe them, so that only by the end of the speech is the image created.

Richard as actor. But that's been done too - David Schofield twisting his

naked body into the Elephant Man at the start of that play.

Somehow have to find a character whose charm is dangerous and whose

humour is cruel.

Tonight I wanted a cigarette for the first time. Resisted it.

Shakespeare Birthday Celebrations. A procession through town with the

flags of every nation unfurled along the way. Last night at The Duck,

Pam was telling us that the police had been wondering all week what to

do about the Libyan flag while the siege in St James's Square continued.

A shop next to the Libyan flagpole was asked, rather ominously, if they

minded being used as a first-aid station. Luckily the siege came to a

peaceful end yesterday, the embassy has been closed down and so the flag

has just been removed altogether.

Reporting the deportation of the embassy staff, the Daily Mirror carries

the headline, `Good Riddance!' Bill recalls similar examples of the tabloids

slang-slinging and rabble-rousing during the Falklands: `Up Yer Junta!',

`Barging the Argies', `Gotcha!' (when the Belgrano was sunk). He says

it's useful to think about Richard's oration to his soldiers in these terms:

`He should aim for a lofty style, a Times editorial, but it should instinctively

come out on the lowest possible News of the World level.' ('A scum of

Bretons ... these bastard Bretons ... shall these enjoy our lands? Lie

with our wives? Ravish our daughters?') `Or to put it another way,' says

Bill, really warming to his theme now, `he aims for the inspiring patriotism

of a Henry the Fifth, "Once more unto the breach" kind of stuff, but all

he can muster is, "Do you want some smelly dago sticking his dick up yer

missus?" '

It does help me to think of Richard's verbal style throughout as that of

a tabloid journalist, that brand of salivating prurience.