Year of the King: An Actor's Diary and Sketchbook - Twentieth Anniversary Edition (17 page)

Read Year of the King: An Actor's Diary and Sketchbook - Twentieth Anniversary Edition Online

Authors: Antony Sher

Tags: #Arts & Photography, #Performing Arts, #Theater, #Acting & Auditioning, #Stagecraft, #Biographies & Memoirs, #Arts & Literature, #Entertainers, #Humor & Entertainment, #Literature & Fiction, #Drama, #British & Irish, #World Literature, #British, #Shakespeare

Barrie comes alongside us smiling gently. Points to another man who

is wearing a crash helmet. He has fallen over so often his face is cut and

bruised like a boxer's - his hands are twisted in such a way that he cannot

break his falls.

Barrie says we're welcome to come back whenever we like. There's a

Richard III lookalike whom he feels we should see but who isn't here

today. We thank him and leave.

Drive back quite dazed.

Charlotte comes round to the house before this evening's visit to the

disabled games group.

'Was yesterday of any use?' she asks.

`Oh yes. But I don't think Richard is a spastic.'

'No.'

'The condition is too convulsive.'

She explains in detail about hunchbacks. Often the condition doesn't

arise until adolescence (and most commonly among girls). There are two

types: scoliosis, and kyphosis.

I instantly decide on the latter. It's what I've been drawing. The bottled

spider, the bull. And it's different from Olivier.

`Anyway,' says Charlotte, `tonight there'll be a much wider range. Every

kind of disability, the mentally ill, the blind, everything.'

`Right,' I say, and down a stiff vodka tonic.

KING EDWARD'S SCHOOL, HAMPSTEAD We wander through the

large dark grounds until we find a brightly lit hall with a fleet of ambulances

parked outside.

The place is buzzing with activity: bowls, table tennis, badminton and

various board games. Also a rather ferocious game of hockey - a crowd of

people charging around wielding sticks, some on foot, some in wheelchairs.

One of the players stops, grins and waves her stick at us: Carol, from the

works centre yesterday, who interrogated me so thoroughly.

Charlotte starts to giggle. `She's going to wonder why we've turned up

again.'

I wave back and whisper through a clenched smile, `Careful. Remember

the lip-reading.'

The organiser, a friend of Charlotte's, comes bounding over from the game, sweating heavily. Charlotte introduces him by his nickname, Bones.

He's a policeman and does this in his spare time. Tall, well built, rugged

good looks of a movie star. His manner is rather brusque: `We don't do

any molly-coddling here, they have to get off their arses and do a bit.'

But he's very gentle with them, reassuring, encouraging, very tactile,

pretending to bully, but with a Hollywood smile that makes all swoon

before him.

Here comes trouble - Carol's helper is wheeling her over. Charlotte

smiles and deserts me.

`What are you doing here?' Carol asks.

`Oh, I'm ... well, it's Charlotte, actually. She's a visiting physio -'

`Will you be coming back to the works centre?'

`Yes, I might.'

'Why?'

`Barrie suggested I should.'

`But why?'

`It was Barrie's suggestion.'

`But what are you doing?'

`I'm a freelance-artist-friend of Charlotte's. Excuse me.'

As I disengage myself I can't help thinking that this has been a perfect

demonstration of Mike Leigh's golden rule for research - always tell the

truth about why you're there.

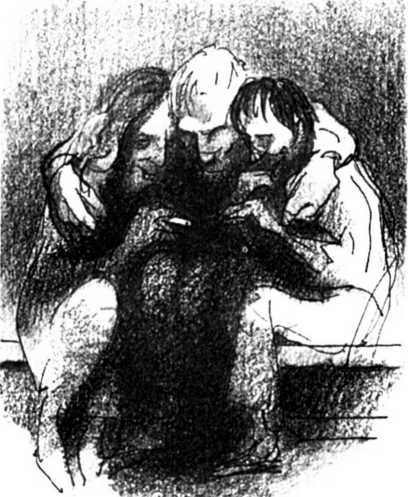

My attention is constantly drawn to a group of three who ignore all the

games and remain totally private. In the middle is a man of about fifty.

His arms are around a young, frail, dark-haired girl on one side, an older

red-haired woman on the other. They move around the hall, heads close

together, whispering.

Bones suggests a visit to the archery club in another hall. He dons an

anorak, lights a cigarette, tells me how the whole thing started as a small

venture and has grown and grown. His endless battles to get money from

the council, to organise transport, to find helpers. The ratio has to be one

helper to two disabled. I tell him that I couldn't distinguish the disabled

from the helpers.

`That's because a lot of them are mentally retarded,' he says, `and

there's no visible disability. When new helpers start, I make it a point not

to tell them who's got what wrong. Let the two sides just meet as people.'

At the archery club they sit in a line of wheelchairs. The skill is

surprising. One young man is blind in one eye and severely spastic. He

battles to fit the arrow in place and then, as he aims, it weaves around dangerously. I try not to flinch as it strays over his shoulder towards me.

But when at last he fires, it is with superb accuracy. Another young man

with frail bony features sits in a strange state: he lifts his bow slowly, fits

an arrow, considers it carefully, unfits it, lowers his bow, never fires.

Back at the main hall, there are several newcomers. One of the new

helpers is a policeman in uniform, a tubby cheerful man who laughs a lot.

He twists his cap back to front, does Goon voices, `Hulloooo, I'm Neddy

Seagoooon', mimes karate chops at a thalidomide lady passing in a

wheelchair. Another new face is a boy called Gordon with a thin ginger

moustache and puffy eyes with scars round them. There is a sense of

suppressed violence about him. Someone bumps into him and he says in

a quiet, clenched voice, `I'm very calm. I'm very calm.' The laughing

policeman aims a karate chop at him. I hold my breath. But Gordon just

says `Yeah', and moves away.

The threesome sit huddled on a bench in a corner. They share a

cigarette, passing it around like a joint. I ask Bones about them. The

young girl is the sister of the boy who never fired his arrow. She is partially

blind. The man in the middle is completely blind and partially deaf. The

red-haired woman is mentally retarded. They each come from different

institutions and live for these Tuesday nights. `We get a lot of love affairs

starting here,' says Bones, `and why not?'

I can start sketching. Enough time has passed, I've blended in. Clamber

up on to an exercise horse, an ideal place because no one can peer over

my shoulder. Constantly looking over towards me, smiling, curious, flirting,

Carol is the only one who takes any notice of me.

Home time. The red-haired lady from the threesome fetches their

coats. They rise and almost as one, weave into the arms, hoods, scarves.

It looks like they're climbing into one huge garment that will bind them

even closer together. But now comes the time for them to be separated

into different ambulances.

I have seen enough. I thank Charlotte and Bones, and leave.

Reading the play in bed, the first scene now seems very familiar. A disabled

man sitting in the sun, grumbling to the audience about his lot (the man

yesterday who said, `Life is unfair'). Powerless to stop his brother being

taken to prison, he makes a few jokes to cheer him up. Passes the time of

day with I lastings: 'What news abroad','

I remember now that my first thought of yesterday was: are these people

smiling, or are they in pain, or are they bearing their teeth like animals

do when threatened? All these expressions are similar. Grinning or

grimacing.

I had set out to look for a physical shape, but maybe what I found is

something about being disabled.

I am going to have to give up smoking and get fitter than ever. And then

keep it up for two years. God.

Jim says I should treat it like an athlete's training for the Olympics, says

it's important enough for me to give up alcohol and go on to special foods.

In the meantime, Bill comes to dinner, we drink a lot of wine, smoke a

lot of cigarettes, and he prepares to tell me what the Richard III set is

going to be. `I'm still a bit nervous about the idea,' he says, `so forgive me

if I have difficulty putting it into words.' And indeed he goes into a very

long preamble about religion in the Middle Ages while I sit on the edge

of my seat stopping myself from screaming `Yes, but what's it going to

be?' His eyes are gleaming with excitement and tension. I do know how

he feels: it's the moment when you have to speak aloud an idea that you've

been nurturing alone and you know the other person's face is instantly

going to tell you whether they think it's a very good idea or a very bad

one. The two are often separated by a hair's breadth.

At last: the play is going to be set in a cathedral, with tombs of dead

kings and high stained glass windows. Obviously it will be a perfect setting

for the religious scenes, but he also wants to use it non-realistically, as if

the play is being done as a medieval morality play, so that the battle at

Bosworth can take place among the tombs - the final duel, St George

and the Dragon.

The concept is stunning, it grips my imagination. As we discovered late

in Tartuffe rehearsals, the other side of religion is a grotesque world of

gargoyles and demons. Perfect for Richard III. For much of the early part

of the play he feigns piety; the wretched cripple who is forced out of the

sensual world into the spiritual one, a holy fool.

Now it's my turn. I show Bill three sketches: the bottled spider, the

head I drew in Hermanus, and Ronnie Kray. I try the crutches idea on

him again and find myself describing a concept which is clearly in the

spider drawing, but which I hadn't actually realised until now: `We play

him as a four-legged creature.' In the text there are many animal references

- boar, hog, toad, spider, hedgehog, and best of all (given the cathedral

setting), `Hell-hound'.

Bill says quietly, `This is terribly exciting.' He reckons that playing

Richard as monstrous as this solves in one stroke the biggest problem in

the play - why is he so evil? Also he points out that Richard's deformity

is only ever mentioned by the others in moments of impassioned cursing,

as if it's so extreme that it's normally unmentionable. So when Margaret really lets rip in Act 1, Scene iii, the others can shield their eyes and think,

`Oh shit, she hasn't gone and mentioned that.'

Without prompting, Bill uses a description I wrote ages ago in Hermanus: `His appearance should provoke both pity and terror.' This keeps

happening in our collaboration - thinking as one.

He stares at my sketch of the bottled spider and wonders whether we

could actually create this image, throw a giant shadow on the wall.

I say, `I'm afraid we used it in King Lear - the front-cloth scene.'

`Ah yes. Adrian Noble has already done it. True of so many things

these days.' He looks up and grins. It's a source of mild inconvenience,

not bitter envy. Bill is not an ambitious man.

He leaves, but the excitement we have generated remains. His reaction

to the spider drawing was so positive. Maybe I have found my nightmare

creature. And now there is a setting for him - this spooky church.

Spend all day doing line run-throughs of Maydays. It's been nine weeks

since we last did it. An awful lot has happened to us all since then - Peter

Pan, Tempest, Much Ado, Moliere, Tartuffe video, and so on.

KING'S HEAD PUB, BARBICAN Before the show, first meeting with

our designer, Bill Dudley. An unexpected personality, but then all designers are the least theatrical, the least neurotic members of the profession.

Or at any rate, their suffering is conducted in the privacy of their

workrooms or the dark of the auditorium. Bill has an East End accent, a

passion for playing his piano accordion in a band that tours pubs, and the

hugest eyebrows I've ever seen. He says he thought so too until he met

Denis Healey at a party. As they leant forward in discussion it was like

two stags about to lock antlers.