Writing the Novel (26 page)

Authors: Lawrence Block,Block

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Reference, #Writing

I wish you luck.

I won’t read your manuscript, or recommend an agent, or put you in touch with a publisher. I’ll answer letters—if I can make the time, and if you enclose a stamped self-addressed envelope. But that’s as much as I’ll do. You have to do the rest yourself. That, I’m afraid is how it works in this business.

I hope you write your novel. I hope you write a lot of them, and that they’re very good books indeed. Not because I would presume to regard your work as a sort of literary grandchild of mine—let’s face it, you’d write it whether or not you read this book.

But simply because, while there are far too many books in this world, there are far too few good ones.

And I don’t ever want to run out of things to read.

In the spring of 1976 I sold a piece to

Writer’s Digest

, the monthly magazine for writers. I was in Los Angeles at the time, in mute testimony to H. L. Mencken’s observation that a Divine Hand had taken hold of the United States by the State of Maine, and lifted, whereupon everything loose wound up in Southern California. The article I sold them was a reply to the perennial question,

Where do you get your ideas?

, and when they accepted it I got an idea on the spot.

My idea was to sell them on the idea of hiring me as a columnist. They had a couple of columnists, but nobody was writing about fiction, and that was the chief interest of most of their audience, so the need seemed to be there. Rather than push this through the mail, I waited until I could do it in person; my daughters flew out in July to spend the summer with me, and we stayed that month in LA and spent the month of August on a leisurely drive back to New York, where they lived with their mother—and where I had lived, until that Divine Hand sent me spinning.

I mapped out our route east so that I could work in a lunch in Cincinnati with John Brady, then the editor at

Writer’s Digest.

He’d bought my article, and over lunch he bought my idea for a fiction column, to run six times a year, alternating with their cartoon column. I got back to New York and sent in the first column, and by the time I’d written the third one they’d booted the cartoonist. My column would appear in the magazine every month for the next fourteen years.

I’d been doing it for a little over a year when Brady got in touch. Their book division felt the need for a book telling how to write a novel. And they liked the way I wrote about writing, and wanted me to do the book for them.

I was living in New York again, in an apartment on Greenwich Street. (It’s no more than a two-minute walk from where I live now, thirty-three years later, but I’ve had a slew of addresses in the interim.) I wrote the book and sent it off, and the folks in Cincinnati liked it just fine, and proposed a title:

Writing the Novel from Plot to Print

.

I didn’t like it at the time, felt it made the whole process sound more mechanical than I thought it to be. I’d made a particular point in my book of not telling the reader, “This is the way to do it.” There were, as I saw it, at least as many ways to do it as there were writers, and arguably as many ways as there were books. But they really liked the title, and I went along with it, and I have to say it seems OK to me now.

The book has remained continually in print for more than thirty years. I guess the title hasn’t hurt it any.

Fifteen years ago, Writer’s Digest Books wanted me to revise

Writing the Novel

. They felt it was dated. I talk about the Gothic novel, for example, and while books fitting that pattern may continue to be written and read, the category by that name has long since ceased to exist. If I could go through it and update it, then they could bring out a new edition with the words “updated new edition” on it, and increase sales accordingly.

I thought about it, and ultimately decided against it. The book seemed to be one readers find useful, and the techniques and principles discussed struck me as essentially timeless, as pertinent in 1995 as they had been in 1978. And the whole idea of updating a book bothers me, anyway. I knew a writer once who’d updated a novel, or tried to; it was being reissued after fifteen or twenty years, and he’d gone through it page by page, updating the cost of a telephone call from a nickel to a dime (this was a few years ago), changing the stars of a movie his character watches from William Powell and Myrna Loy to William Holden and June Havoc (yes, this was a while ago), and otherwise altering the book’s temporal setting.

Well, it didn’t work. One way or another, every word in that book was attached to the year it was written. It had a certain integrity, and you altered it at your peril.

Writing the Novel

is not a novel, and thus may not need to adhere to the same standard of artistic integrity, but it’s nonetheless a creature of the time of its writing, and my inclination is to leave it alone. I’m also predisposed to avoid work, and this looked to me to be work to no purpose.

Now, fifteen years after I decided the book wasn’t broke and didn’t need to be fixed, it is in fact another decade and a half older, and that much further out of date. But it still ain’t broke, as I can tell by the enthusiastic word-of-blog I keep encountering on the Internet, and I’m still predisposed to avoid work. So I’m not fixing it. I hope it does for you all a book of this sort can possibly hope to do. I hope it helps you speak in your own voice, map out your own route, and find your very own way to your very own book.

Bon voyage!

—Lawrence Block

Greenwich Village

Lawrence Block ([email protected]) welcomes your email responses; he reads them all, and replies when he can.

Lawrence Block (b. 1938) is the recipient of a Grand Master Award from the Mystery Writers of America and an internationally renowned bestselling author. His prolific career spans over one hundred books, including four bestselling series as well as dozens of short stories, articles, and books on writing. He has won four Edgar and Shamus Awards, two Falcon Awards from the Maltese Falcon Society of Japan, the Nero and Philip Marlowe Awards, a Lifetime Achievement Award from the Private Eye Writers of America, and the Cartier Diamond Dagger from the Crime Writers Association of the United Kingdom. In France, he has been awarded the title Grand Maitre du Roman Noir and has twice received the Societe 813 trophy.

Born in Buffalo, New York, Block attended Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio. Leaving school before graduation, he moved to New York City, a locale that features prominently in most of his works. His earliest published writing appeared in the 1950s, frequently under pseudonyms, and many of these novels are now considered classics of the pulp fiction genre. During his early writing years, Block also worked in the mailroom of a publishing house and reviewed the submission slush pile for a literary agency. He has cited the latter experience as a valuable lesson for a beginning writer.

Block’s first short story, “You Can’t Lose,” was published in 1957 in

Manhunt

, the first of dozens of short stories and articles that he would publish over the years in publications including

American Heritage

,

Redbook

,

Playboy

,

Cosmopolitan

,

GQ

, and the

New York Times

. His short fiction has been featured and reprinted in over eleven collections including

Enough Rope

(2002), which is comprised of eighty-four of his short stories.

In 1966, Block introduced the insomniac protagonist Evan Tanner in the novel

The Thief Who Couldn’t Sleep

. Block’s diverse heroes also include the urbane and witty bookseller—and thief-on-the-side—Bernie Rhodenbarr; the gritty recovering alcoholic and private investigator Matthew Scudder; and Chip Harrison, the comical assistant to a private investigator with a Nero Wolfe fixation who appears in

No Score

,

Chip Harrison Scores Again

,

Make Out with Murder

, and

The Topless Tulip Caper

. Block has also written several short stories and novels featuring Keller, a professional hit man. Block’s work is praised for his richly imagined and varied characters and frequent use of humor.

A father of three daughters, Block lives in New York City with his second wife, Lynne. When he isn’t touring or attending mystery conventions, he and Lynne are frequent travelers, as members of the Travelers’ Century Club for nearly a decade now, and have visited about 150 countries.

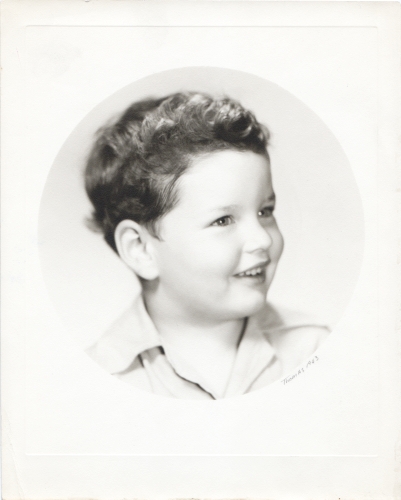

A four-year-old Block in 1942.

Block during the summer of 1944, with his baby sister, Betsy.

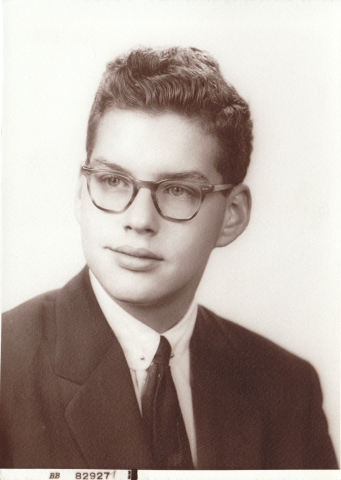

Block’s 1955 yearbook picture from Bennett High School in Buffalo, New York.

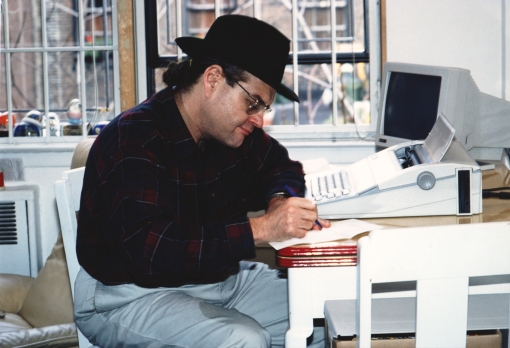

Block in 1983, in a cap and leather jacket. Block says that he “later lost the cap, and some son of a bitch stole the jacket. Don’t even ask about the hair.”

Block with his eldest daughter, Amy, at her wedding in October 1984.