Writing Home (41 page)

Authors: Alan Bennett

In this process of recovery the ‘what-whatting’ was crucial. This verbal habit of the King’s was presumably the attempt of a nervous and self-conscious man to prevent the conversation

from flagging – always a danger in chats with the monarch, since the subject is never certain whether he or she is expected to reply or when. The onset of the King’s mania delivered him from self-consciousness and so the ‘what-whatting’ went; the King was in any case talking too fast and too continuously for there to be need or room for it. When he began to calm down and come to himself again he came to the ‘what-whatting’ too, the flag of social distress now a signal of recovery. As Greville wrote, ‘though not a grace in language, yet the restoring habits of former days prescribed a forerunner of returning wisdom.’

I have no experience of royal persons, some of whom I think may still ‘what-what’ a little. Today, though, it’s easier. What royalty wants nowadays is deference without awe, though what they get more often than not is a fatuous smile, any social awkwardness veiled in nervous laughter so that the Queen moves among her people buoyed up on waves of obliging hilarity. How happy we must all seem! Such tittering would have been unthinkable at the court of George III, reputedly the dullest in Europe, where no one laughed or coughed, and where it was unthinkable ever to sneeze.

Had the King insisted on such formality outside the court he would not have been as popular as he was. A stickler for etiquette at home, he and the Queen remained seated while his courtiers stood for hours at a time, drooping with boredom: but outside the court, often riding unattended, the King would stop and chat with farm labourers, road-menders and anybody he came across. When they went to Cheltenham he promised the Queen, with a lack of formality that not so long ago was thought to be a modern breakthrough, that they would ‘walk about and meet his subjects’.

One difficulty when writing the play was how to furnish the audience with sufficient information about the political set-up at the end of the eighteenth century for them to understand why

the illness of the King threatened the survival of the government. Nowadays, of course, it wouldn’t, and the fact that there were seemingly two parties, Tories and Whigs, could mislead an audience into thinking that nowadays and those days are much the same.

What has to be understood is that in 1788 the monarch was still the engine of the nation. The King would choose as his chief minister a politician who could muster enough support in the House of Commons to give him a majority. Today it is the other way round: the majority in the Commons determines the choice of Prime Minister. Though this sometimes seemed to be the case even in the eighteenth century, a minister imposed on the King by Parliament could not last long: this was why George III so much resented Fox, who was briefly his Prime Minister following a disreputable coalition with North in 1783. All governments were to some degree coalitions, and a majority in the Commons did not reflect some overall victory by Whigs or Tories in a general election. Leading figures in Parliament had their groups of supporters; there were Pittites, Foxites, Rock-ingham Whigs and Grenvilles, who voted as their patron voted. A ministry was put together, a majority accumulated out of an alliance of various groups, and what maintained that alliance was the uninterrupted flow of political patronage, the network of offices and appointments available to those running the administration. In the play Sir Boothby Skrymshir and his nephew Ramsden are a ridiculous pair, but, as Sheridan says (though the phrase was actually used by Fox), they are the ‘marketable flotsam’ out of which a majority was constructed. At the head of the pyramid was the King. All appointments flowed from him. If he was incapacitated and his powers transferred to his son, support for the ministry would dwindle because the flow of patronage had stopped. If the King was mad, it would not be long before the Ins were Out.

As I struggled to mince these chunks of information into credible morsels of dialogue (the danger always being that characters are telling each other what they know in their bones), I often felt it would have been simpler to call the audience in a quarter of an hour early and give them a short curtain lecture on the nature of eighteenth-century politics before getting on with the play proper.

The characters are largely historical. Margaret Nicholson’s attempt on the King’s life was in 1786, not just before his illness as in the play; but it is certainly true, as the King remarks, that in France she would not have got off so lightly. As it was, she lived on in Bedlam long after the witnesses to her deed were dead, surviving until the eve of the accession of George III’s granddaughter, Queen Victoria.

I thought I had invented Fitzroy but discover that in 1801 George III had an aide-de-camp of this name, who was later the heart-throb of the King’s youngest daughter, Amelia. He was ‘generally admitted to be good-looking in a rather wooden sort of way, he had neither dash nor charm and seems to have been on the frigid side into the bargain,’ which describes our Fitzroy exactly. That he was playing a double game and was an intimate of the Prince of Wales is my invention.

Greville is a historical character, his diary one of the most important sources for the history of the royal malady. However, Greville was not in attendance throughout as he is in the play. A fair-minded though conventional man, and clear-sighted where the King’s illness was concerned (and often appalled at its treatment), Greville along with the King’s other attendants was excluded when Dr Willis, ‘the mad doctor’, took on the case. Willis brought with him some of his own staff, presumably from his asylum at Greatham in Lincolnshire, and took on other heavies in London. In the play they appear only once, when the restraining-chair is brought in at the end of the first act, but in

fact they remained at Windsor and Kew in constant attendance on the King until Willis eventually went back north. This was not, as in the play, immediately before the thanksgiving service in June 1789, but some months later.

The number of physicians attending the King varied. They were known as the ‘London doctors’, to distinguish them from Dr Willis and his son. I have restricted them to three, but there may have been as many as ten. Nor have I included Willis’s son, who was also a doctor and in charge of the King during his next attack in 1802.

The pages who in the play bear so much of the burden of the King’s illness were probably older than I have made them, the youngest and kindest, Papandiek, being the King’s barber, with his wife another of those who kept a diary of this much journalized episode. Some pages were sacked when the King recovered, because ‘from the manner in which they had been obliged to attend on Him during the illness, they had obtained a sort of familiarity which now would not be pleasing to Him.’ However, these were not Papandiek and Braun. In the play depicted as a heartless creature, Braun was in fact one of the King’s favourites, and still in his service ten years later. The other page, Fortnum, left to found the grocer’s, and in the seventies, I remember, one used to be accosted in the store in far-from-eighteenth-century language by two bewigged figures, Mr Fortnum and Mr Mason – actually two unemployed actors.

I found the Opposition (an anachronistic phrase for which there is no convenient substitute) much harder to write than the government. ‘What can they

do

?’ Nicholas Hytner would ask, which is the same question of course that Opposition politicians are always having to ask themselves, even today. Pitt, Dundas and Thurlow carry on the government; Fox, Sheridan and Burke can only talk about the day when they might have the government to carry on. And drink, of course. But, as the King

says, ‘they all drink.’ Pitt was frequently drunk before a big speech, and on one occasion was sick behind the Speaker’s chair.

With Pitt I had first to rid myself of the picture I retained of him from childhood, when I saw Korda’s wartime propaganda film

The Young Mr Pitt

. Robert Donat was Pitt, kitted out with a kindly housekeeper, adoring chums and maybe even a girlfriend. At one point in the play he talks of when he was a boy, though boy he never really was, brought up by his father to be Prime Minister, destined always for ‘the first employments’. The son, the nephew and the first cousin of Prime Ministers, the only commoner in a Cabinet of peers, perhaps he was arrogant – but no wonder. Long, lank and awkward, he made a wonderful caricature, and if he was the first Prime Minister in the sense we understand it today it was because, as Pares says, the cartoonists made him so.

Pitt’s career ran in tandem with that of Fox, though Fox was the older man. Meeting the boy Pitt, he seems to have had a premonition that here was his destiny. They are such inveterate and complementary opposites – Pitt cold, distant and calculating; Fox warm, convivial and impulsive – that they are almost archetypes: save or squander, hoard or spend, Gladstone and Disraeli, Robespierre and Danton, Eliot and Pound. Pitt had his disciples, but Fox, for all his inconsistencies and political folly, was genuinely loved, even by his opponents (though never by the King). His oratory was spellbinding, as Pitt ruefully acknowledged (‘Ah,’ he said to one of Fox’s critics, ‘but you have never been under the wand of the magician’). Burke, whom posterity remembers as a great orator, was in his day considered a bore, his speeches often ludicrously over the top, and known as ‘the dinner bell’ because when he rose to speak he regularly emptied the House.

Fox had charm, even at his lowest ebb. ‘I have led a sad life,’ he wrote to his mistress:

sitting up late, always either at the House of Commons or gaming, and losing my money every night that I have played. Getting up late, of course, and finding people in my room so that I have never had the morning time to myself, and have gone out as soon as I could, though generally very late, to get rid of them, so that I have scarce ever had a moment to write. You have heard how poor a figure we made in numbers on the slave trade, but I spoke I believe very well … and it is a cause in which one cannot help being pleased with oneself for having done right.

Baffled as to how to convey Fox’s charm, I included much of this letter in the first draft of the play, the speech originally part of the much altered final scene. ‘A danger this is becoming Fox’s story,’ noted Nicholas Hytner, so I took it out again.

I made Sheridan a man of business, a manager of the House, and he was certainly more canny than Fox, whom he regularly scolded and who, he always said, treated him as if he were a swindler. I began by peppering his speeches with self-quotation, which is never a wise move. I had done the same with Orton in an early draft of the screenplay of

Prick Up Your Ears

, and that hadn’t worked either; one thinks, too, of all the movies about Wilde in which he talks in epigrams throughout. There was originally a parody of the screen scene in

School for Scandal

, in which the Prince of Wales and his doctor are discovered hiding from the King. It had some basis in fact, but it was an early casualty. I give him two shots at explaining it, but what I find hard to understand is why, having made a name for himself in the theatre, Sheridan should have wanted to go into politics at all. On the rare occasions I have talked to politicians I have found myself condescended to because I’m not ‘in the know’. (Political journalists and civil servants do it too.) So perhaps that was part of it. Poor Sheridan never quite managed to be one of the boys, even in death. In Westminster Abbey, Pitt, Fox and Burke are buried clubbily together, whereas Sheridan has landed up next to Garrick. His distaste for this location wa another casualty of the final scene of the play. Of course what really wanted to include, but didn’t dare, was the playwright’ bane: a conversation (with Thurlow, it would be), beginning ‘Anything in the pipeline, Sheridan?’

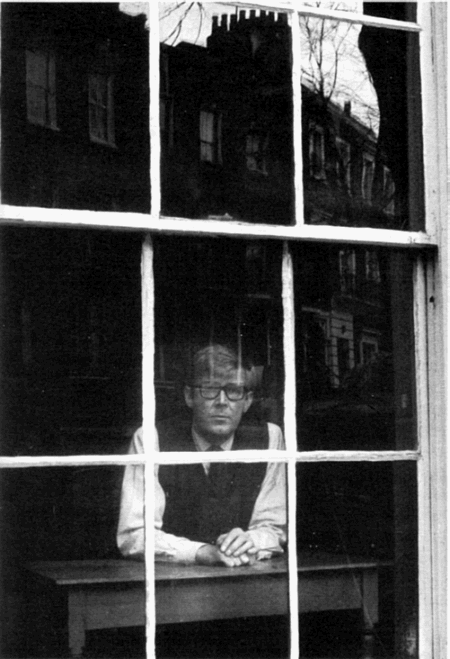

26 Camden Town, 1982

27

An Englishman Abroad

, Dundee, 1983, Coral Browne and Alan Bates

28

An Englishman Abroad

(left to right: Alan Bates, Bates, Innes Lloyd, Ken Pearce, A. B. and John Schlesinger)