Wreckage (17 page)

Authors: Niall Griffiths

Some small augmentation now to this city’s sense of rage and shame and although it cannot be witnessed swimming in the oily harbour pools or prowling the roof like one of the feral felids that are a further secret populace of this conurbation it is nonetheless here. Not in any acceleration or deceleration of the general pace of living nor in any inflective altering of the collective voice if such a hubbub polyglot and motley, pidgin and patois could ever be encapsulated in such a term but nonetheless here it is. Devoid of tangibility or immediacy maybe it can be located in some incipience that hangs like a stormcloud or smog in a coming perturbance, in the individual lives that are yet to be startled in some specific way and which move at the moment unknowing and thus in a bliss of some sort, universal if acknowledged but since it never is then scarce-seen, lurking rarefied in these individual lives. Maybe something of it in the chance splat of the raindrop on the pecking pigeon’s head and in the sudden flight of that dirty bird from the gutter and the startling of the Japanese tourist and in his flinching and his accidental striking of the mother with the pram and in the toppling of that pram and the spillage of shopping but not child and the overlooked tangerine and, later, the old lady’s foot which will squash that fruit

on

the slippery sidewalk and which will buckle and maybe in the weakened decalcified ankle bone that will snap. And maybe then in the citizen who will stop and administer and the ambulance driver and the concerned family members who will gather at hospital bedside and so on and so on and so on and maybe in such a causal chain unheeded and unstated, maybe only in its waiting-to-happen, maybe only in the falling raindrop and the as-yet-undisturbed city bird pecking in the gutter at a discarded kebab are such tiny additions detectable; these new sparks of rage and shame located as yet only in the what-is-to-come, the what-will-be.

And, too, there is something else. Something that can be seen in propulsion, in matters of striding, in a notion of happiness even bound as that term is to ideas of determination and purpose and goal and aim. In a sense of something to do. In the eternal perversity that drives the heart through and between the diurnal traffic and that which appears desultory and often is on some level beneath the need for bread or attire because how can the way be possibly lit by a purpose that remains unknown? How can the route through a plan be followed if its architecture was drawn up in a language arcane? Or if the training of a light upon it casts only a deeper, blacker shadow?

Darren moves from pub to pub, and does not drink in any. In each, there are surreptitious glances at the discolorations and scabs on his face and the stitches in his scalp but his eyes are seldom met and in every bar he stands among the seated drinkers with his big bruised head pivoting on his big neck like a predator

seeking

prey. Twice he is asked by bar staff who he is looking for but on each occasion he merely shakes his head and leaves the pub and moves on to the next one to be ticked off on his mental itinerary, a list of the places where Alastair might be. One of these is Ye Cracke.

The barman recognises his face, even under the blueness and blackened blood. He’s seen it many times before. Heeds the mental alarm bells that clatter in his head but does not ask anything of Darren, only keeps one eye on him as one of the old men who daily gather in the corner by the beer-garden door, the old feller with the limp and the cane, shouts him over:

—Hi, Darren! C’meer, son!

Darren goes to him.

—Alright, Grandad.

—Jeez, lad, what happened to the face? Battlin again, av yeh?

This old man pushes a stool away from the table with his cane and Darren sits down on it and shrugs.

—Ah, y’know, Grandad. Just some gobshites in town, like, that’s all. Too many of em.

—Oh aye?

—Aye, yeh. Two against one, like. Did me best like but … adder friggin pool cue, one of em.

Darren shrugs again. The old man’s faded blue eyes drift over the beaten face of his grandson and the pupils are as black as the Guinness that rises to touch the thin bloodless lips that slowly sip. He replaces the pint on the table top and shakes his head sadly and in disgust.

—Two against one, ye say? Tooled up n all? Ach,

friggin

cowards. Nowt down for them types. If there’s one thing I can’t stand it’s –

—Shite-arse spineless bastards, Grandad, yeh, I know. Yer’ve said before.

—Aye, well, you watch out for them toerags, son. Only look after themselves, like, an don’t give two fucks who else might suffer as a consequence. Cowards. Human race’s fuller them, lad. See, in the war, we –

—Ah, Grandad, I’m rushed off me friggin feet. Don’t av the time right now.

—Oh aye, well? What is it yer’ve got to do that’s so important that yeh haven’t got the time for yer ahl grandad? Not gunner be around much longer an yer’ll regret it then, won’t yeh?

—I’m lookin for someone. And indeed Darren’s eyes do now scan the bar. —Got somethin to sort out, likes.

Who?

—Alastair.

—That dopey sod, always wearing the cap?

—That’s him, yeh. Seen im?

—Not for a few weeks, no. Last time I saw

him

he was with you in the Caledonian.

A plangent chord rings out. A band is setting up on the long bench beneath the big mirror; fiddle, bodhrán, squeeze box, acoustic guitar, penny whistle and gobiron. Warm-up notes ring and wheeze and tootle in the smoke-strata’d air.

—Yeh, well, knob’ed’s gone AWOL. Need to find him soon as.

—Ach, you’ve got time for a pint, sure. Yer mother’s been askin about yeh, worried sick she is. Cheer her

up

a wee bit if I can tell her I shared a glass with yeh, won’t it? Surely yeh not so busy that ye can’t share a pint with yer grandad, by fuck.

Darren sighs and rubs a hand across his face then winces and sucks air as he irritates a tender spot beneath his eye. The old man opposite him, he is of his blood. The old man opposite him still limps from a wound suffered when fighting overwhelming odds, a fight which he seems to recall sharply and clearly because he has recounted it to Darren in tremendous detail and often enough so that Darren could tell the tale too. The old man opposite him and who is of his blood, he fought his way hand-to-hand out of an irrigation ditch in France into which a shellburst had blown him and armed only with a pistol and a knife and an entrenching tool and trying to protect his old schoolmate Ernie Riley who sadly died of his wounds. The old man opposite, he has seen and done things at the furthest extremes of human experience. He is of the rarest breed of men and also of his blood. The closest thing to a hero Darren has ever encountered and something of what drives him and has driven him through the shocks and horrors of the world successfully for nearly eighty years in some wise must drive Darren too.

—Aye, go on then, Grandad. I could merda a Guinness.

—Good boy.

The old man shouts to the barman and holds up two fingers, lumped and warty and arthritically crooked of knuckle and with deep orange nicotine discolorations at the tips. The barman nods and pours the pints.

—Have ye eaten, son?

—Nah.

—Could yiz go a ham roll?

—Nah, yer alright, Grandad. Guinness’ll do.

—Pint of the black soup, eh?

—Yeh.

Without counting in and thus seemingly of telepathic timing precise and coordinated completely the band launch into a reel, a frantic swirling tune which instantly into this quiet mid-afternoon fuggy pub injects a note of hysteria or rather concretises the hysteria that constantly hovers in such places, in the grey layers of smoke that hang and drift and the sets of boots and trainers on the dusty floor or bar rail and certainly the contours of the faces that confront alcohol with aggression, isolated as they are and must always be from the sun and traffic both human and mechanical that blares beyond the windows of frosted glass. The lifting loops and movements of this music expanding then contracting and repeating themselves more frenzied with each fevered recalled phrase jabbers of the ditch and drink and desperation it was born in like a secret tongue concocted subterranean or in some other place where the sanctioned thief could never reach between sweating stone or sap-bubbling branch, any place where steam might gather both surrounding and enervated by the heart heated by all defiance and insistent in its relentless hypnosis of the reaching blood. Behind sockets and sterna such common force could stamp itself on the indifferent world only in this one unique expression and its high-tensile resistance, each instrument fluent and conversant with the next in this

language

alien to the human tongue yet familiar to and in fact borne over in many breasts, able to reflect the landscape it leaps from even if that be smoke-yellow ceilings and booze-stained wood and torn cushion, providing these brush against the tingling skin and the gulping eye. Only that these bellies have sifted a hundred hungers and found one they can accommodate, that the hearts are aware that the staying of their pain will be brief and fleeting, only until each instrument and the fleshy hands and throats that draw such huge sounds from them will dwindle and fall mute.

—D’yeh like the reel, Darren?

—Aye, Grandad, yeh. It’s sound.

—In ’45 I was demobbed with a bunch of Irish fellers over in Galway. Stayed there months, I did,

months

. Loved it, me. Learnt to play the banjo. Bet yeh didn’t know I could play thee ahl banjo, did yeh?

—News to me.

—Aye, well, there’s a packet of things yeh don’t know about me, lad.

—Bet there is, Grandad.

Darren drinks his Guinness quickly and orders two more and hears the old man’s voice like glass against glass in his ear, behind the music. And further behind it there is Alastair and those two fucking neds and vengeance like a hooded shade with spread vulture wings and behind that further still is a thing burning hot and blood red but as long as the music leaps and frantics and the old warrior who is of his blood continues to growl words Darren can drown it, let it momentarily fade like the throb of pain in his bruised

face

and scalp split and stuck. Can, while his head is otherwise engaged, convince himself that there is no shame here, in this mid-city pub on a weekday early afternoon, among these people of courage and defiance, no shame whatsoever. Little fucking scallies just caught him unawares, that’s all. Bushwhacked him from behind, like. Little fucking cowards. They’ll get it. Like all cowards the world over, as the old man says, they’ll get fucking

theirs

.

The music must stop, eventually. It always does. But Darren’ll be up and moving long before then.

Alastair needs a piss. There’s a growing pressure in his bladder as if in there a fist is slowly clenching. He’s not bursting yet but he’s getting there and as he walks down Rice Lane and past Ye Cracke he hears an Irish jig start up suddenly inside and considers availing himself of the toilets in there but reasons that it will probably be dead busy and the two fucking neds, that Robbo and Freddy they call themselves, won’t be in there because Ye Cracke doesn’t have a pool table and they seemed big big fans of the game when he first met them in Lime Street Station bar. That and betrayal, oh fuck yeh, big frigging fans of

that

as well. Little pair of shites. Probably down Bold Street now spunking the entire wedge on trainees and fucking anoraks but not for bleeding long, oh fuck

no

.

He exits Rice Lane, traverses the cobbles on to Hardman Street where outside the ten-til-ten offy he gets begged on four times and God he thinks these

must

be frigging desperate if they’re asking

me

for odds. Do I

look

like I’ve got any spare change, lar? He passes

St

Luke’s, destroyed sixty years ago by

Luftwaffe

bombs and left as a charred shell to commemorate that war and in the grounds of its blackened wreckage just beyond the padlocked gates some stela has been erected, a tall upright monolith attached to which is an empty bowl, monument to those who died in the Great Hunger and too to those who fled from that wasting many of whom washed up on these shores here and built the railways and the waterfront and also places of worship like this one now devastated, a scorched hulk central to this city of many edifices flame-gutted alike although not all at Nazi hands. ‘An babhla folamh’ are the words carved into this standing stone above the empty bowl which to Alastair has always looked horribly, howlingly empty, a terrible void that never fails to make his stomach groan whenever he passes it. Sometimes the sky will fill it with slimy rain and it then becomes a birdbath for sparrows and starlings and pigeons and other city birds but for the most part it remains empty adjacent to the charred church hollowed by flame and sprouted around by large flowering shrubs through which once drifted the attenuated shapes of junkies jacking up until for a reason recondite and known only to their peculiar migratory instincts they moved to the gardens of the Anglican cathedral, the spire of which can be seen skyscraping over the burnt twin of St Luke’s like an overlord, a terrible perpetual reminder of this world’s wrecking whims.

Alastair remembers the unveiling of the empty-bowl monument. Remembers Mary Robinson getting out of the limo, and all the cheering crowds. And

remembers

too her phalanx of bodyguards, big fridge-like men in overcoats with cropped hair and reflector shades and gun bulges. They were dead cool, he thought. Dead friggin don’t-mess-with-me-cunt. He’d like to be one of them.

He crosses the road on to Renshaw Street and sticks his head around the door of the Dispensary but sees only old men and a pool table unattended and slanting beams of diluted light and he intends to cut across on to Bold Street to check the greater number of pubs and caffs there but the need to urinate is now urgent so he veers into the Egg, climbs the narrow stairwell plastered with flyers for bands and plays and readings and squeezes through the thin doors into the caff proper where ah good fuckin Jesus there’s a

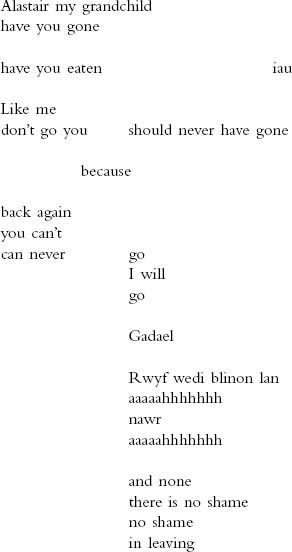

poet

. He’s between Alastair and the toilets, standing there before a small audience single figures and going on in a poncey non-local voice about ‘savers’ or something, some such shite. About ‘wanting whisky’ or something. Ally shifts from foot to foot, not wanting to disturb this reader embarrassing as he is or indeed expose himself to the audience small as it is but it’s no good, he’s gunner pee his kex, so he darts across between the poet and his audience and hears a sudden silence broken only by a tut and a snigger and can feel eyes on him but fucks to that he’s in the bogs and his knob is out of his trackies he’s letting it all out steaming, relief.