Would You Kill the Fat Man (22 page)

Read Would You Kill the Fat Man Online

Authors: David Edmonds

• • •

Despite the furious denunciation by Foot’s friend, Elizabeth Anscombe, Harry Truman was awarded his Oxford honorary doctorate. He rather dismissively called it his “floppy hat” degree, referring to the black velvet headgear that honorands are required to wear. Before the ceremony, he gave a press conference denying any knowledge of the furor that Anscombe had created. “The English are very polite. They kept it from me.”

2

And he reiterated that he had no regrets about dropping the

atomic bomb. “If I had to do it again, I would do it all over again.”

3

He entered the Sheldonian at midday on June 20, 1956 to “God Save the Queen,” and wearing his vivid scarlet robe, took his place on an eighteenth-century mahogany hall chair, decorated with elaborate coats of arms, and reserved for just this occasion. All around the theater applause broke out, redoubling as Truman stood and bowed.

• • •

Anscombe herself stayed away from the ceremony—to no one’s surprise. She was quoted by a newspaper as saying she would spend the day working as usual. But the arguments she deployed in her tirade against Truman were influential in not only shifting Catholic policy on war (the Catholic Church in Rome had remained almost entirely silent about the aerial bombardments of German cities in World War II), but, more generally, in having “Just War” theory accepted within the military and beyond.

Her academic career blossomed. She became Professor of Philosophy at Cambridge University in 1970. This had been her mentor Ludwig Wittgenstein’s post. She remained a staunch Roman Catholic and was twice arrested protesting outside an abortion clinic. She retired in 1986, died in 2001, and was buried in a grave next to Wittgenstein. She and Pip Foot had drifted apart: Anscombe admitted to always feeling terrible that she couldn’t convince Foot that there was a God.

• • •

Iris Murdoch died in 1999, having spent the last few years of her life suffering from Alzheimer’s disease, a period that was

documented in a book by her husband John Bailey, and later turned into a successful movie,

Iris

. It is said that when Murdoch became ill, Philippa Foot was one of the very few people with whom she could be left alone without becoming agitated.

4

Murdoch will be remembered more for her novels than for her philosophy. She once said that she had loved Foot, “more than I ever thought I could love any woman,”

5

and Foot appears in various guises in Murdoch’s novels. But when Murdoch died, Foot admitted that there was something about Murdoch she’d always found unfathomable. “We lived together for two years in the war, and she and I were the closest of friends to the end. Yet I never felt I altogether knew her….”

6

• • •

The cannibal case of

Regina v. Dudley and Stephens

, which had caused such a sensation in the late Victorian era, was soon forgotten in Britain. Dudley and Stephens, prisoners 5331 and 5332, returned to jail to serve their shortened sentence. On his release, Dudley emigrated to Australia: he died in 1900 at just forty-six years old after contracting bubonic plague. Stephens returned to a seafaring life: it’s thought he became depressed and took to drink. He died in poverty. Brooks salvaged the story from complete obscurity by appearing on several occasions in “amusement shows,” the nineteenth-century version of the celebrity circuit.

• • •

After the operation on their conjoined twins, in which Mary died but Jodie survived, Rina Attard and her husband moved back to the island of Goma, off Malta, and live with Jodie quietly

there still. They are reported to be pleased in retrospect that the legal judgment went against them.

• • •

As for the quasi ticking-bomb–like scenario in Germany, Magnus Gäfgen was convicted and sentenced to life imprisonment for murder and kidnapping with extortion. But the legal ramifications rumbled on for years. The case eventually went to the European Court of Human Rights, where Germany was convicted of violating the prohibition against torture and inhuman and degrading treatment. Gäfgen also sued the state of Hesse, demanding compensation for the trauma he experienced from the torture threat. In 2011, a German court awarded him 3,000 Euros in damages. The police officer behind the torture threat, Wolfgang Daschner, had already been fined and transferred to other duties. Meanwhile, Gäfgen had completed his law degree, though his plan to establish “a Gäfgen Foundation” to help child victims of crime was withdrawn—the authorities said they would never permit it to be registered.

• • •

For the past half century, trolleyology has provided a vehicle to contest fundamental issues in ethics—vital questions about how we should treat others and live our lives. When Philippa Foot introduced the trolley problem it was to intervene in the debate over abortion. Nowadays, a trolley-like challenge is more likely to arise in deliberations about the legitimacy of types of conduct in warfare. Churchill’s dilemma—about whether to attempt to redirect rockets to less populous areas—continues

to be reincarnated in a variety of other forms too. The Fat Man quandary highlights the stark clash between deontological and utilitarian ethics. Most people do not have utilitarian instincts (as utilitarians themselves acknowledge). They believe that Winston Churchill would have been wrong to use citizens as a human shield, even if his objective was to save the lives of others. He would have been equally wrong to force or inveigle people into the path of a Nazi threat, even if in order to save lives. But, on balance, he was surely right to support the deception plot to redirect the doodlebugs toward south London.

Why the difference? Philosophers still can’t agree. But whatever the answer, the strange situation of the fat man on the footbridge must hold the key. I wouldn’t kill the fat man. Would you?

Appendix

Ten Trolleys: A Rerun

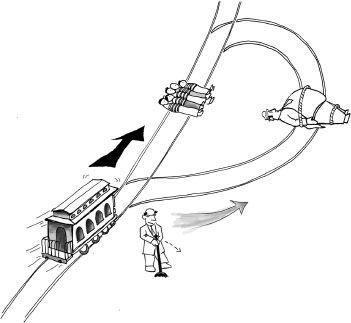

Figure 1.

Spur.

You’re standing by the side of a track when you see a runaway train hurtling toward you: clearly the brakes have failed. Ahead are five people, tied to the track. If you do nothing, the five will be run over and killed. Luckily you are next to a signal switch: turning this switch will send the out-of-control train down a side track, a spur, just ahead of you. Alas, there’s a snag: on the spur you spot one person tied to the track: changing direction will inevitably result in this person being killed. What should you do?

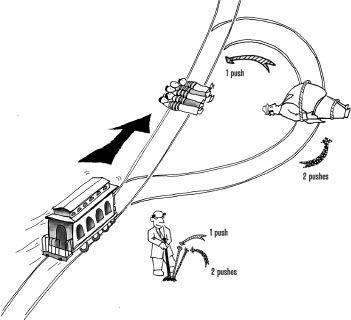

Figure 2.

Fat Man.

You’re on a footbridge overlooking the railway track. You see the trolley hurtling along the track and, ahead of it, five people tied to the rails. Can these five be saved? Again, the moral philosopher has cunningly arranged matters so that they can be. There’s a very fat man leaning over the railing watching the trolley. If you were to push him over the footbridge, he would tumble down and smash on to the track below. He’s so obese that his bulk would bring the trolley to a shuddering halt. Sadly, the process would kill the fat man. But it would save the other five. Should you push the fat man?

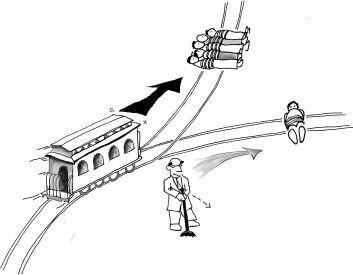

Figure 3.

Lazy Susan.

In Lazy Susan you can save the five by twisting the revolving plate 180 degrees—this will have the unfortunate consequence of placing one man directly in the path of the train. Should you rotate the Lazy Susan?

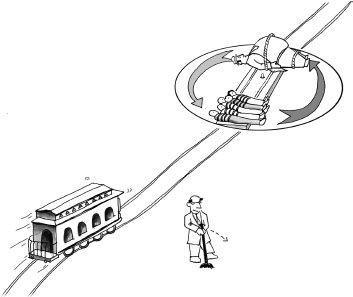

Figure 4.

Loop.

The trolley is heading toward five men who, as it happens, are all skinny. If the trolley were to collide into them they would die, but their combined bulk would stop the train. You could instead turn the trolley onto a loop. One fat man is tied onto the loop. His weight alone will stop the trolley, preventing it from continuing around the loop and killing the five. Should you turn the trolley down the loop?

Figure 5.

Six Behind One.

You are standing on the side of the track. A runaway trolley is hurtling toward you. Ahead are five people, tied to the track. If you do nothing, the five will be run over and killed. Luckily you are next to a signal switch: turning this switch will send the out-of-control trolley down a side track, a spur, just ahead of you. On the spur you see one person tied to the track: changing direction will inevitably result in this person being killed. Behind the one person are six people, also tied to the track. The one person, if hit, will stop the trolley. What should you do?

This example is from Otsuka 2008.