World War II Behind Closed Doors (33 page)

Read World War II Behind Closed Doors Online

Authors: Laurence Rees

‘I'm sure that the leaders of both the Allies understood they might have been bugged’, says Zoya Zarubina,

8

who was a Soviet intelligence officer, liasing with the press in Tehran at the time. ‘But there was nothing to be done, you can't avoid that…. You bugged our hotel rooms when we came to Britain – don't tell me that it's not proper’.

At a quarter past three on 28 November 1943, Roosevelt and Stalin met for the first time when the Soviet leader came to call on the American President as he settled into his rooms in the Soviet legation. Superficially, two more different leaders it is hard to imagine. Zoya Zarubina, who saw both in Tehran, describes Stalin as having ‘a tired face…and if you are closer you can see [his] smallpox spots. And the one thing that surprised you is the eyes. His eyes were, I don't know… well, golden yellowish, let's call it that way. But once, all of a sudden, you get eyeball to eyeball it is scary – scary in the sense that he just pierces through you’.

Roosevelt, on the other hand, ‘his eyes were always smiling at you. I don't know what he thought, but you know, [his eyes were] sort of inviting you to come on, speak up’.

Roosevelt greeted Stalin with the words: ‘I am glad to see you. I have tried for a long time to bring this about’.

9

Stalin pointedly replied that he was to blame for the delay since he had been ‘very occupied because of military matters’. That first encounter lasted about an hour, and is notable chiefly for the way Roosevelt was prepared to criticize the absent Churchill. The President mentioned that Churchill's attitude to India (the Prime Minister was opposed to Indian independence) meant that ‘it would be better not to discuss the question of India with Mr Churchill, since the latter had no solution of that question, and merely proposed to defer the entire solution to the end of the war’. Stalin agreed that India was Churchill's ‘sore spot’. Then, in an overt attempt at ingratiating himself with Stalin, Roosevelt suggested that India should be reshaped ‘somewhat on the Soviet line’. Stalin remarked that this would mean ‘revolution’.

It is not surprising that Roosevelt used the question of India, and thus implicitly the British Empire, in an attempt to create an immediate bond with Stalin. The American President had always disapproved of the British Empire – as far as he was concerned, the sooner it was dismantled the better. Indeed, it is important to remember, says George Elsey, that whilst the Americans recognized that Stalin's regime was ‘pretty despicable’ it was also the case ‘that in the United States there were a significant number of people who were not very comfortable with the British Empire either. There was a sizeable vocal minority who questioned whether we should be spending so much to preserve the British Empire. So there was scepticism about Britain, there was scepticism about the Soviet Union’. At the Yalta Conference, just over a year later, Roosevelt was to demonstrate further his anti-colonial stance by suggesting to Stalin that Britain should give up Hong Kong to China.

Churchill, wholly committed to the British Empire, did little to hide his views on the subject – views that he knew were anathema

to the American administration. He memorably remarked to Charles Taussig, one of Roosevelt's foreign policy advisers, that: ‘We will not let the Hottentots by popular vote throw the white people into the sea’.

10

This, naturally, was an attitude which fuelled Roosevelt's suspicion that the British were fighting the war – in part at least – to preserve the empire. In the autumn of 1944 Roosevelt said to Henry Morgenthau, the Secretary for the Treasury, that ‘he knew why the British wanted to join the war in the Pacific. All they want is Singapore back’.

11

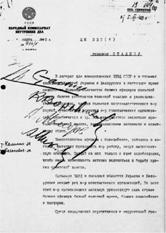

The document that led to the Katyn massacre. Stalin's agreement – scrawled in blue crayon – on Beria's proposal of 5 March 1940 to ‘try before special tribunals’ selected Polish citizens who were ‘sworn enemies of Soviet authority’.

Molotov (seated), Ribbentrop (standing left) and Stalin at the moment the Nazi-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact was signed in the Kremlin in August 1939. Stalin, as this picture shows, was happy and at ease with the Nazi Foreign Minister.

Finnish troops on exercise. They were shortly to fight during the war against the Soviet Union in the winter of 1939–40. The Finns initially had success against a Red Army that vastly outnumbered them.

Molotov (left) and Hitler during the Soviet Foreign Minister's visit to Berlin in November 1940. The trip was not a success.

Soviet troops cross into eastern Poland in the autumn of 1939. The secret part of the Nazi-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact had decreed that this area of Poland was in the Soviet ‘sphere of influence’.

Red Army soldiers surrender to a German tank unit in the summer of 1941. The Germans took 3 million Soviet prisoners in the first seven months of the war.

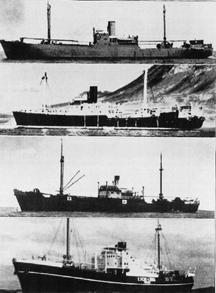

The German auxiliary cruiser

Komet

(Comet) in a variety of different guises. The ship, which sailed across the top of the Soviet Union in 1940, was regularly repainted, renamed and disguised in order to prevent detection.

German officers discuss with a Soviet officer (far left) the demarcation line between their various pieces of conquered territory after the signing of the Nazi-Soviet pact.