World War II Behind Closed Doors (23 page)

Read World War II Behind Closed Doors Online

Authors: Laurence Rees

‘The convoy just started disintegrating’, says Frank Hewitt,

86

who sailed on PQ17. ‘And everyone was completely demoralized’. In such circumstances an order for the convoy to ‘scatter’ was tantamount to an order for it to self-destruct. ‘[We] couldn't believe it’, says Hewitt. ‘Unbelievable…to think that the navy would desert a convoy. It just didn't make sense…[the speed of] the slowest ship was about four knots and they were just sitting ducks’.

Frank Hewitt was a sailor on board HMS

La Malouine

, one of the naval escort vessels that was ordered to proceed to the Barents Sea and thence to Archangel on its own: ‘We felt that we were deserting them [the merchant ships of the convoy], and in fact we were’. On their way to the Soviet Union they picked up lifeboats full of survivors from the ships that had been sunk by the German bombers and U-boats, and Hewitt recalls one story told to him by the crew of an American merchantman they rescued from the sea: ‘They were telling us that a submarine surfaced and the skipper said: “I'm sorry, gentlemen, I shall have to sink your ship. War is war. I will give you ten minutes to take to the boats. Have you got sufficient provisions for the journey? Good luck”. And then

another lot of survivors that we picked up, they said much the same sort of thing. A U-boat surfaced: “I'm very sorry, gentlemen. War is war. I shall have to sink your ship. You've got ten minutes to take to the boats. Why fight for the Bolsheviks? You're not Bolshevik, are you?”’

Hewitt had his own almost chivalrous dealings with a German U-boat when he was on anti-submarine patrol out of Archangel in the north of the Soviet Union: ‘We were sailing along the edge of the ice-cap and a submarine surfaced, perhaps half a mile ahead, to charge his batteries. So, of course, we gave chase…. We took a shot at them. We had a four-inch gun, which was our biggest armament, but it fell short of the submarine. And on his Aldis lamp he flashed back: “Missed me! Try again”. And I suppose our skipper replied: “We'll keep trying”. And this went on for four or five hours, and then he decided he'd charged his batteries sufficiently well, so he said: “Thanks for the chase. We'll be leaving you now. Good luck”. And then dived under the ice’.

Frank Hewitt's encounter with the German U-boat off the coast of Archangel demonstrated the ineffectiveness of the British navy during this crucial period of the war in the Arctic. For the reality was that the Admiralty advice about the dangers of running convoys in the long northern summer had been correct. And that, coupled with the false intelligence about the movement of the

Tirpitz

, had brought disaster. Of the 39 ships in PQ17, 24 were destroyed – more than 60 per cent of the convoy. A total of 153 merchant seamen lost their lives, and just under 100,000 tons of war material went to the bottom of the sea – including 210 bombers, 430 tanks and over 3000 other vehicles.

Not surprisingly, as a result of the PQ17 disaster, convoys to the Soviet Union were temporarily suspended.

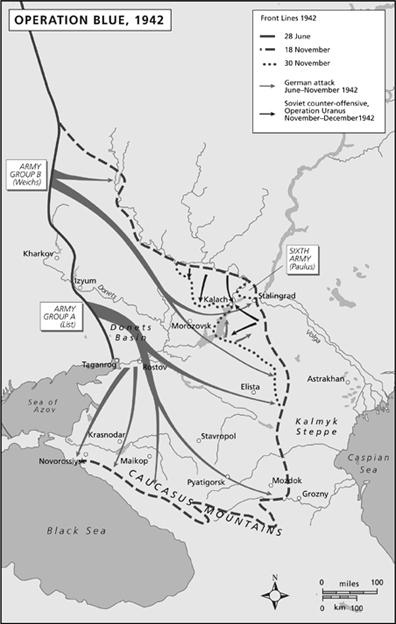

Now, in the summer of 1942, Churchill contemplated the Allied surrender at Tobruk in North Africa, the destruction of PQ17 in the Arctic, and the swift advance across the steppes of the German army in the wildly successful Operation Blue. From the Allied perspective it was a bleak picture. Indeed, it looked as if it was perfectly possible that the Allies might lose the war.

Churchill knew that one of the keys to eventual victory was the Soviet Union. The Soviet people were bearing the brunt of the German attack. It was essential that Stalin keep the morale of the Red Army high and – most important of all – not contemplate any attempt to extricate himself and his people from the war. But Churchill was also aware of the effect that recent events would have on Stalin. The Western Allies would not open a second front in 1942 – the defeat at Tobruk, as well as other more minor military setbacks, ruled the operation out completely – and after PQ17 convoys to the north had, for the time being, ceased. The Soviet leader would not take this news well. So Churchill did what he most often did when faced with a crisis: he confronted it head on. He would, he announced, make the journey to Moscow in a converted British bomber, and explain to Stalin personally why the Allies couldn't do what the Soviet leadership had demanded. He would fly nearly 2000 miles, in great discomfort, in an attempt to preserve the vital relationship with Stalin.

3

CRISIS OF FAITH

MEETING STALIN

While the Germans were advancing through the steppes of southern Russia in the summer of 1942, Nikolai Baibakov, Deputy Minister for Soviet Oil Production, hurried to see Stalin at his office in the senate building of the Kremlin.

‘I'd had about five meetings with Stalin before that one’, says Baibakov,

1

then one of the Soviet Union's top oil engineers, ‘and he made a very big impression on me…. They were very business-like meetings. Joseph Stalin always showed interest in the state of affairs in the oil industry and he attached a lot of significance to its developments’. But this particular meeting was to be of more significance than the others. Baibakov was shown into Stalin's office, and in this ‘calm’ atmosphere waited expectantly for his leader to speak.

‘Comrade Baibakov’, said Stalin, ‘Hitler is rushing to the Kavkaz [Caucasus]. He has announced that if he doesn't seize the Kavkaz oil, then he'll lose the war. Everything must be done so that not a single drop of oil should fall to the Germans’. Baibakov was told that his job was to travel to the Caucasus and ensure that the Germans didn't get hold of any oil. But then Stalin added – and at this point, Baibakov recalls, his voice became ‘a touch crueller’: ‘Bear in mind that if you leave the Germans even one ton of oil, we will shoot you. But if you destroy the supplies prematurely, and the Germans wouldn't have managed to capture them anyway and we're left without fuel, then we will also shoot you’.

2

Perhaps surprisingly, Baibakov considers that Stalin's method of motivating him was ‘justified’. ‘Of course if I had made a mistake it would have been a crime’, he says. ‘It would have been

a crime if I had left the oilfields for the Germans. I would have gone against my country’. Yet Baibakov also admits that he would have ‘done his best’ to try to protect the oilfields without this blatant threat from Stalin. Intriguingly, he seems to feel that the fact that the Soviet leader had taken time in his packed schedule to threaten him personally was almost a badge of honour, a sign that he was being entrusted with an especially important task. ‘Perhaps I would have said the same thing if I had been in his place’, he says. ‘The end justifies the means’.

Ultimately, of course, Nikolai Baibakov survived, since the Germans never came close enough to the oilfields he was ordered to protect for him to have to make the decision whether to destroy them or not. But Stalin's method of inspiring Baibakov to do his job, together with Baibakov's total acceptance of it, is nonetheless instructive. It demonstrates the extent to which straightforward brutality was at the core of Stalin's leadership technique. He believed that if you really want someone to do something, if their task is monumentally important, you must make sure they know that if they mess it up they will die.

Around this same time, Churchill was en route to Moscow for his own series of meetings with the Soviet leader. The relationship between Britain and the Soviet Union was clearly deteriorating. On 18 July 1942 Churchill had written to Stalin and delivered the bad news about supplies and the second front. Stalin had, not surprisingly, been less than happy with this communication and had replied on the 23rd with a cold and accusatory telegram: ‘I received your message of 18 July’,

3

wrote the Soviet leader. ‘Two conclusions could be drawn from it. First, the British government refuses to continue the sending of war materials to the Soviet Union via the northern route. Second, in spite of the agreed communiqué concerning the urgent task of creating a second front in 1942, the British government postpones this matter until 1943’. After this devastating opening, in which he effectively accused Britain of breaking direct promises to the Soviet Union, Stalin asserted that his own military and naval experts found the reasons for the stopping of the convoys ‘wholly unconvincing’. ‘Of

course’, he wrote, ‘I do not think that regular convoys to the Soviet northern ports could be made without risk or losses. But in wartime no important undertaking could be made without risk or losses. In any case, I never expected that the British government would stop despatch of war materials to us just at the very moment when the Soviet Union, in view of the serious situation on the Soviet-German front, requires these materials more than ever…. I must state in the most emphatic manner that the Soviet government cannot acquiesce in the postponement of a second front in Europe until 1943’. Stalin ended with the clearly disingenuous hope that Churchill ‘will not feel offended that I expressed frankly and honestly my own opinion’.

Sir Archibald Clark Kerr, the extrovert and somewhat eccentric British ambassador in Moscow who had replaced the solemn Sir Stafford Cripps in February 1942, was clear about what lay behind Stalin's harsh and non-diplomatic language. In a cable to London on 25 July he wrote that in his view the Soviet leadership didn't believe ‘that we are yet taking the war seriously. They set up their own enormous losses against our (by comparison) trifling losses in men and material since the close of 1939’.

4

And three days later, on 28 July, Clark Kerr suggested that the Prime Minister should visit Moscow in an attempt to placate Stalin personally.

Churchill realized that he had to make the arduous journey, even though he did not relish the prospect of a conference with Stalin at this difficult time. Before he left he told his doctor, Charles Wilson, later Lord Moran, that he was not looking forward to the meeting because Stalin ‘won't like what I have to say to him’,

5

and he later wrote that he felt his journey to Moscow ‘was like carrying a large lump of ice to the North Pole’.

6

But it was General Sir Alan Brooke, Chief of the Imperial General Staff, who most succinctly expressed the problem the British faced: ‘We were going into the lion's den and we weren't going to feed him’.

7

Churchill flew out in an unheated and unpressurized American bomber, wearing an oxygen mask that had a special attachment that allowed him to smoke cigars, and eventually, after a stop-over in Cairo, where he berated his commanders for their poor showing

against Rommel, arrived in Moscow on 12 August 1942. At seven o'clock that evening he had his first encounter with the Soviet leader at the Kremlin. The setting was Stalin's office on the second floor of the senate building. In appearance it was in stark contrast to the aristocratic opulence of Blenheim Palace, where Churchill had been born, and even to Chequers, the country house retreat outside London that the Prime Minister had at his disposal. Stalin didn't just dress simply, he lived and worked simply too. His office was gloomy, with uncomfortable wooden chairs set around a rectangular conference table. In the far corner stood his writing desk, beneath a photograph of Lenin reading

Pravda

. On the other walls there were pictures of Marx and Engels. In one corner was a tiled Russian stove. Oppressive wooden panelling encased the room to shoulder height, and throughout the room there was a faint smell of polish and tobacco.

As soon as Churchill had sat down at the conference table, Stalin began by announcing that the news from the front line was ‘not good’ and that the Germans were forcing their way to Stalingrad and Baku. He was certain that ‘they had drained the whole of Europe of troops’. Then, against this depressing background, with even the official British minutes describing Stalin as looking ‘very grave’,

8

Churchill launched straight into his bad news. He reiterated that Molotov had previously been told that the British could make ‘no promises’ about a second front in 1942 and that ‘the British and American Governments did not feel able to undertake a major operation in September…. But, as Mr Stalin knew, the British and American Governments were preparing for a very great operation in 1943’.

The official minutes describe Stalin as looking ‘very glum’ after Churchill had finished his lengthy explanation of just why the British and the Americans were not going to help the Soviet Union with a second front in 1942. Clearly exasperated by Churchill's words, Stalin announced that ‘there is not a single German division in France of any value’. Churchill replied that there were ‘25 divisions in France’. Stalin retorted that ‘A man who was not prepared to take risks could not win a war’.

The Prime Minister tried to lighten the mood by talking about one practical way in which the British and Americans were already providing help to the war effort – the bombing campaign. Stalin immediately remarked that ‘It was not only German industry that should be bombed, but the population too’. Then Churchill, in a statement at odds with his later attempt to distance himself from the ‘terror’ bombing campaign towards the end of the war, stated unequivocally that ‘As regards the civilian population [of Germany], we looked upon its morale as a military target. We sought no mercy and would show no mercy’.