World of Water (11 page)

Another organic submarine, the bulbous eyes mounted at its front housing another pair of pilots.

One of the pilots was busy communicating with the two Tritonians in the other vessel. Dev watched incredibly complex light patterns flicker over their faces, a back-and-forth three-way dialogue. The exchange moved too swiftly and was too convoluted for him to follow properly, but he got the gist of it.

The manta sub pilot appeared to be saying that the human – Dev – was to be left alone. The cuttlefish sub pilots were unhappy about this and felt that no human, not even one who was part-Tritonian, should be immune from harm. Their wrath was great, as proved by the punishment they and their fellows had meted out on the giant surface ship that would soon be afloat no more. No one should escape it.

The manta sub pilot insisted that Dev should be spared. He was...

Dev could not really grasp the next bit.

Different? Unusual? Rare?

He had the impression that the manta sub pilot was talking from experience, as though Dev was a known quantity.

Peering, he realised that they

had

met before. At least, he thought so. It was the female Tritonian who had helped save him from the thalassoraptor. Her co-pilot was the male who had killed the predator deftly with his spear.

Dev wasn’t one hundred per cent sure it was the same two Tritonians. He wasn’t familiar enough with the indigenes to distinguish them one from another easily. Their features were all somewhat similar, and he hadn’t yet worked out which physical characteristics were the crucial ones, the ones to look for in order to tell them apart.

But the female had that scarified nautilus design at her breastbone. How many other Tritonians bore that?

He didn’t know the answer, but it was too much of a coincidence to disregard, especially when she was defending him to other members of her race as though he and she weren’t strangers.

The question of why the Tritonian couple happened to be here, hundreds of kilometres south of Tangaroa, in the exact same spot at the exact same moment as Dev, was something he would have to address later. For now, he was simply glad that the female was interceding on his behalf, making the case for him being allowed to live.

It looked as though she was winning the argument, too. The Tritonians in the cuttlefish sub were exhibiting less hostility, more consent. The lights on their faces suggested that they considered themselves satisfied with the havoc they had wrought on the

Egersund

and its crew. One more human death, one fewer – what did they care?

If sighing had been possible underwater, Dev would have breathed a sigh of relief.

Three things happened next, in quick succession.

First, the

Egersund

seemed to have had enough. It had taken on too much water. It could no longer stay upright. It gave in.

The whaler slowly capsized, with a roar of tortured metal and roiling water. It was like watching a mountainside collapsing, a steady, unremitting black avalanche. The sea erupted into a nightmare of turbulence as the ship’s quarter-million tonnage bore down into it, and down, and further down.

Dev felt himself being pushed bodily backwards by the wake of the ship’s collapse. Both the cuttlefish sub and the manta sub were shaken about, too.

The second thing that happened was that hands seized Dev under the armpits and he was hauled away from the capsizing

Egersund

and the Tritonian submarines. He glimpsed diving gear – wetsuits, full-foot swim fins, compact oxygenated-crystal rebreathers – and could only assume he had been grabbed by Marines from the

Admiral Winterbrook

. The divers had turbine-driven jetpacks on their backs and were forging through the water at close to twenty knots.

The third thing was a subaquatic explosion, a fireball blossoming somewhere by the Tritonian vessels, a sphere of brilliance encased in a glassy shell of bubbles. The detonation was sharp-sounding, a brief noise-spike amid the ongoing cacophony of the

Egersund

’s demise.

The afterimage of the explosion lingered in Dev’s retinas like a gibbous moon as the Marines spirited him further and further away from the scene of chaos. They were travelling so fast that he found it hard to breathe. All he could do was keep his head tucked in, open his mouth as wide as it would go, and suck in as much as he could of the water surging past.

He hoped he could last. He hoped he wouldn’t black out. He hoped the Marines would slow down before he did lose consciousness and couldn’t force water through his gills anymore. He hoped he wasn’t going to become the first amphibious human being ever to drown.

17

B

Y THE TIME

Dev was safely aboard the

Admiral Winterbrook

, the excitement was over.

The

Egersund

was gone, plummeting through thousands of fathoms into the icy gulfs of Triton’s ocean, dragging the redback carcass with it. An oil slick, a smattering of flotsam and a patch of troubled sea were all that was left to show for it.

The manta sub and the cuttlefish sub were gone too. Gunnery Sergeant Jiang had deployed three torpedoes against the Tritonian vessels. After the first of them detonated, the submarines had dived; the next two torpedoes had been fired more to deter a return visit than in hopes of scoring a hit.

Dev’s subaquatic saviours were Private Reyes and Private Cully, the team’s diving experts. Their brief had been to drag him clear of the danger zone, then rendezvous with the catamaran once Jiang had determined that the Tritonians had skedaddled. The fact that they had almost killed him during the rescue was not something Dev would hold against them. Alive was alive, however you got there.

Sigursdottir tore into him, demanding to know what he’d thought he was doing. “Why didn’t you head for the surface like the rest of us? Why’d you hang back? What was going through your tiny little mind?”

“It’s complicated. There was that cuttlefish sub...”

“So you thought you’d stop and sightsee, is that it? Just float there like an idiot, making a target of yourself.”

“I was communicating. The Tritonians were curious about me, and I had an idea I might be able to negotiate with them.”

“And then another bunch of them came along, and you were basically pincered. They could have taken you out any time they liked. Lucky for you, Reyes and Cully were suited up and ready to go. I had them on standby just in case. If they hadn’t swooped in and grabbed you when they did...”

“Don’t get me wrong, I’m not ungrateful. But even if the Tritonians in the cuttlefish sub weren’t going to listen to reason, the ones in the manta sub would have. They weren’t like the other lot. They were a different kettle of fish – wait, is that racist?”

“Different? In what way?”

Dev shrugged noncommittally. “Less radical, I suppose. Moderate. I don’t know for sure, but I’m wondering if not all Tritonians are the same. There are factions. Different degrees of resentment. They’re not all fanatical human-haters.”

“You’re saying there are good Tritonians as well as bad ones?”

“Seems so.”

“Well, duh,” said Sigursdottir, rolling her eyes. “Of course. We’d be nuts if we thought every last one of them was a ruthless revolutionary.

That

would be racist. Trouble is, in the midst of a conflict situation you can’t necessarily tell the sheep from the goats and you don’t have time to make distinctions. You have to assume every indigene is an enemy combatant and act accordingly. Otherwise you might make a mistake – the sort of mistake you don’t get the chance to learn from.”

“I don’t disagree with that,” Dev said. “But if you want to create more of those ruthless revolutionaries, lobbing torpedoes indiscriminately at friendlies and hostiles alike is a good way of doing it. Friendlies can turn into unfriendlies fairly quickly.”

“Yes, well, thanks for the advice, Harmer, and fuck you. I could have left you down there. I could have told Reyes and Cully to stay put on the

Winterbrook

and not risk their necks to save yours. If I didn’t have my orders, I probably would have. For you to stand here and lecture me on how to deal with insurgents – that’s the icing on the turd. I’ve been stationed on Triton for three long years. I know how shit goes down on this planet. You don’t come waltzing in out of nowhere and tell me how to do my job. You don’t have that right.”

There were witnesses to this exchange, which took place on the

Admiral Winterbrook

’s bridge. Corporal Milgrom was there, and so was Gunnery Sergeant Jiang, a woman so petite that next to the hulking Milgrom she looked like a schoolgirl. Even the diminutive Sigursdottir stood a head taller than her. Jiang’s size spoke of an upbringing on one of the ergonomically compact Sino-Nipponese asteroid collectives. No one was that short except by design.

Milgrom, for her part, stood menacingly at Sigursdottir’s shoulder to let Dev know that everything her commanding officer said, she backed to the hilt – the hilt of the shimmerknife she was lovingly fondling. Jiang outranked Milgrom and was the second most senior Marine on board, but it was clear which of them regarded herself as Sigursdottir’s XO and adjutant.

Dev was annoyed that the

Admiral Winterbrook

had attacked the manta sub, but he knew that antagonising Sigursdottir any further would be counterproductive. The Marines were tolerating him at best. It would be pointless to give them a reason to actively hate him.

“Look, all right,” he said. “What’s done is done. I don’t want to get into politics or counterinsurgency tactics or any of that. Handling the Tritonians, that’s your concern. Mine is trying to establish how far Polis Plus is involved in their activities, if at all. So you do your thing, I’ll do my thing, and let’s somehow meet in the middle. Okay?”

Sigursdottir was somewhat mollified, but evidently couldn’t let him off in front of her subordinates. She said, “Yeah, well, stop behaving like a prize chump and that should be possible. By the way, your nose is bleeding.”

“Shit.” Dev put a hand to his face and came away with a glistening palmful of blood. Sigursdottir sent Milgrom to fetch a first aid kit, and shortly Dev had a coagulant-impregnated absorption pad pressed to his nose.

“Got a sanitary napkin if you’d prefer,” Milgrom said with a grin.

“This’ll do fine, thanks.”

“Must’ve been the torpedo,” said Sigursdottir. “Shockwave burst your sinuses.”

“Must have been. Hold on a second. Call coming in.”

Harmer? Handler. What’s up? I got your message, and when I came out on deck, there was a massive ship sinking and the

Admiral Winterbrook

firing torpedoes left, right and centre. I leave you alone for a few hours...

Yeah, you missed some big fun, Manhandler. I’ll fill you in when I come back over. I’m probably going to need more of your magic medicine, too. I’ve started getting nosebleeds.

That’s a bad sign.

No, really?

“I should be getting back to the jetboat,” Dev said to Sigursdottir. “Handler’s giving me grief.”

“Off you go, then,” said Sigursdottir. “Missing you already.”

“Yeah,” said Milgrom, wiping away an imaginary tear. “Don’t be a stranger, you hear?”

18

T

HE TWO BOATS

resumed their journey south. Next on their itinerary was a refuelling stop at the township of Llyr, some 300 kilometres away on the fringes of the Tropics of Lei Gong.

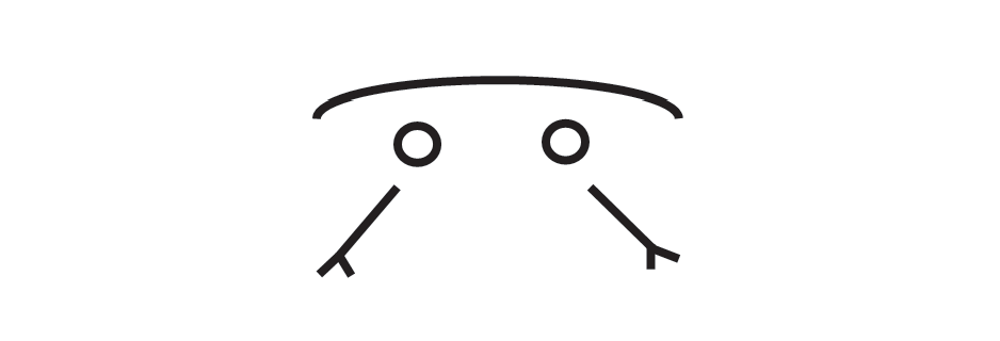

After Dev had brought Handler up to speed on recent events, he asked him about the symbol the Tritonians had made out of the wreckage of the harpoon cannon.

Rather than describe it verbally, he drew a simple picture using his commplant’s sketch function and beamed it to Handler: