Words Like Coins (3 page)

Authors: Robin Hobb

Tags: #fantasy, #pecksies, #hedge-witch, #magic, #charms, #pregnancy, #high fantasy, #Robin Hobb

Mirrifen had begun to lower the bucket into the well. When she heard the splash, she speculated aloud, “If I give water only to you, only you are bound. The others receive the water from you, not me.”

“As you say,” the pecksie grudgingly replied.

“So shall it be. I have no desire to bind pecksies.” But even as she spoke, she wondered if she were foolish. If she withheld the water and forced them to beg for it, could she not bind all of them? And command all of them? They could do more than kill rats.

Or would they swarm her and take the water she taunted them with? Jami said they were vicious. She believed that pecksies had killed her mother.

She set the dripping bucket down before the pecksie. “I give this to you, pecksie.”

“Thank you. I am bound,” she replied formally. Then she turned to the rat butchers and twittered like a bat squeaking. They left off their butchering to mob the water. Some steadied the bucket while others hung head-down, drinking. And drinking. They emerged panting as if sating their thirsts had almost exhausted them. Mirrifen knew better than to offer to help. Instead she studied them. She imagined the long-fingered hands clutching at her, the sharp little teeth biting, dozens of them dragging her down. Yes. They could do that. Would they have? The pregnant pecksie presiding over the water didn’t seem spiteful and vicious. But then, she was bound, and at Mirrifen’s mercy. Perhaps she chose to present a fair face.

When the bucket was empty, it was smeared all over with silvery pecksie dust. The pecksie bowed and gravely asked, “May I have another bucket of water, mistress?”

“You may.”

Mirrifen was still lowering the bucket when the pecksie spoke. “You thought about saying ‘no’ to me. To make all beg water and bind all to you. But you didn’t. Why?”

Mirrifen presented the dripping bucket to the pecksie. She decided not to share all her thoughts. Counting her words like coins, she replied, “I’ve been bound that way. I promised to serve a hedge-witch in exchange for being taught the trade. I kept her house and tended her garden and even rubbed her smelly old feet. I kept my word but she didn’t keep hers. I ended up half-taught, my years wasted. Such a binding breeds hate.”

The pecksie nodded slowly. “A good answer.” She cocked her head. “Then, you never command me?”

“I might,” Mirrifen said slowly.

The pecksie narrowed her green eyes. “To what? To kill rats? To guard well?”

“You already kill rats. You will guard the well, because you want clean water. I don’t need to command you to do that.”

The pecksie nodded approvingly. “That is well said. No need to spend words to bind pecksie. So. You not bind pecksie?”

Mirrifen cleared her throat. Time to make Jami safe. “You must never harm Jami’s baby.” She recalled Jami’s words, that pecksies counted words as precisely as a miser counted coins. This pecksie could still command other pecksies to do what she could not. She revised her dictum. “You must never allow harm to come to her baby.”

The pecksie stared up at her. In the lamplight, her silvery face turned stony. “So. You bind me.” She turned away from Mirrifen. She spoke to the night. “Almost I like you. Almost I think you are careful, deserve to be taught. But you believe stupid, cruel story. You throw words like stones. You insult pecksie. But I am bound. I obey. Not to harm the child, nor allow harm to come to it.” The pecksie shook her head. “Careless words are dangerous. To all.” She walked off. Mirrifen held up her lantern and watched her go. The hunters had all vanished, carrying their prey with them. Night was fading. The edge of an early summer dawn touched the horizon. Mirrifen went back to the farmhouse.

A few hours later, Mirrifen rose to do the morning chores. Jami slept on. There were fewer signs of rats in the house. Outside by the well, smudges of pecksie dust and smears of rat blood on the dry ground were the only signs of last night’s visits.

She began to see signs of pecksies. The tracks of small bare feet on the dusty path. A smudge of silver near the cow’s water bucket. A fall of dust made her glance up. A pecksie slept, careless as a cat, on the rafter of the cow’s stall. Inside the chicken coop, she found all the hens alive and gathered half a dozen eggs. A silvery smear on one nesting box made her wonder if there had been seven eggs. When she spotted another pecksie sleeping soundly under the front steps, she hurried up them without stopping. The rats were gone, but now they were infested with pecksies. It unnerved her but it would do worse to Jami if she saw one.

Mirrifen scrambled eggs with milk and cut up the last of the week’s bread. She had a steaming breakfast on the table when Jami emerged rubbing her eyes. She looked awful. Before Mirrifen could speak, she said, “I had nightmares all night. I dreamed pecksies stole my baby. I dreamed they’d attacked you by the well and killed you. I awoke near dawn, but I was too great a coward to get out of bed and see if you were all right. I just lay there, trembling and wondering if the pecksies would kill me next.”

“I’m sorry you had such bad dreams. But as you see, I’m fine. Sit down and eat.”

“I wish the men would come back. Drake would drive the pecksies away. I wish you’d had more hedge-witch training. Then you could make a charm to keep rats from the well and pecksies from the house.”

Mirrifen bowed her head to that comment, trying not to feel rebuked. “I wish I knew how to make such charms. We’ll just have to think of another way to deal with rats and pecksies.”

Jami suggested fearfully, “Perhaps we could try my mother’s trick. Leave food and water out for them, then bind them and send them away. They’d probably come for water.”

“I don’t think we need to do that, dear. I’ll sleep beside you tonight, not out by the well.”

“Why?”

Mirrifen gathered her courage. Yesterday, it had been hard to tell Jami that she must guard the well at night. It was even harder to tell her why she didn’t need to do it anymore. She divulged the whole truth, of the injured pecksie and the binding with milk and finally of her command to the pecksie. Jamie flushed and then grew pale with fury.

“How could you?” she demanded when Mirrifen paused. “How could you bring a pecksie into this house after what I told you?”

“It was before you told me. I’ve made things right. I bound her not to do your baby any harm.”

“You should send her away!” Jami’s voice shook. “Withhold the water until they beg, then give it, bind them, and send them away! It’s the only safe thing to do.”

“I don’t think that’s right.” Mirrifen tried to speak calmly. She and Jami seldom quarreled. “The pecksie doesn’t seem dangerous to me. She seems, well, not that different from you and me, Jami. She’s pregnant. I think she may be a pecksie hedge-witch. She said—“

“You promised Drake you’d take care of me. You promised! And now you’re letting pecksies into the house. How could you be so false?” She leaped to her feet and rushed from the room, leaving her food half-eaten on the table. The bedroom door slammed. As she sighed in resignation, she heard a piercing shriek. The door was flung open so hard it bounded off the wall. Jami burst into the kitchen. “Pecksies! Pecksies were in my room last night! I didn’t dream it, I didn’t! Look, go and look!”

Mirrifen hurried to the bedroom and peered in. The room was empty. But on the floor in the corner, there was a bloody smudge by the silvery outlines of small feet. “It just killed a rat there,” she said.

“And that? There?” Jami pointed accusingly at a smear of silvery tracks that ascended and crossed the bedclothes. Her finger swung again. “And there?” Silver smeared the windowsill. “What was it doing here? What did it want?” Jami’s voice rose to the edge of hysteria. Mirrifen suspected that a pecksie had pursued a rat across the bed. She tried to sound comforting.

“I don’t know. But I’ll find out how they got in and block it off. And I won’t sleep tonight. I’ll keep watch over you.”

The younger woman was torn between accepting her protection and displaying her anger at Mirrifen for bringing a pecksie into the house. Jami spent the rest of the day penduluming between the two reactions. Mirrifen devoted her hours to tightening the room against rats. In a corner, behind Jami’s hope chest, the floor had sagged away from the wall, leaving a gap wide enough for a rat to slither through. The pecksie had obviously come through the open window. She found an old plank in the barn to mend the gap. As she came back to the house, she saw a pecksie clinging to the windowsill, peering into the bedroom. When she walked toward it, the pecksie sidled away quickly into the tall dry grass. The grasses didn’t even sway after it.

That night, Mirrifen shut the door and the window tightly, and sat by the bed on a straight-backed chair. Long before midnight, her back and her head ached. She yawned and promised herself that tomorrow, after her chores, she’d take a long nap. A long nap, all by herself, stretched out in her own bed.

A tap on her knee woke her. She looked around at the darkness, momentarily bewildered. Pale moonlight cut between the thin curtains to slice the bed. Jami breathed evenly and deeply. Another tap on her knee brought her gaze down. The pecksie stood at her feet, looking up at her. Two more pecksies sat on the window sill. Three perched like birds on the footboard of the bed. All the pecksies stared at Jami intently. Mirrifen’s pecksie spoke. “Mistress, may I have a bucket of water?”

The door to the room was still shut. “How did you get in here?” Mirrifen’s voice shook slightly.

“By a way no rat could come. You bound me. ‘Let no harm come to her child.’ I must keep watch, to be sure it is so. These others serve me in that geas. Yours was the binding. How I fulfill it cannot concern you.

“Mistress, may I have a bucket of water?”

“I can keep watch over her myself,” Mirrifen asserted shakily.

The pecksie shook her head sadly. “You spend your words in lies. You didn’t guard. You slept. I am bound. Guard her I must.”

Mirrifen rose stiffly from the chair. She crept from the room, the pecksie following. She motioned frantically for the others to follow but they did not take their gazes from Jami. She glanced at her pecksie beseechingly. The little woman shook her head stubbornly. “You spent the words, and this is what they bought you.” Mirrifen felt like a traitor as she left Jami sleeping under the pecksies’ watchful eyes. Her pecksie waited impatiently while she lit a lantern to give her courage.

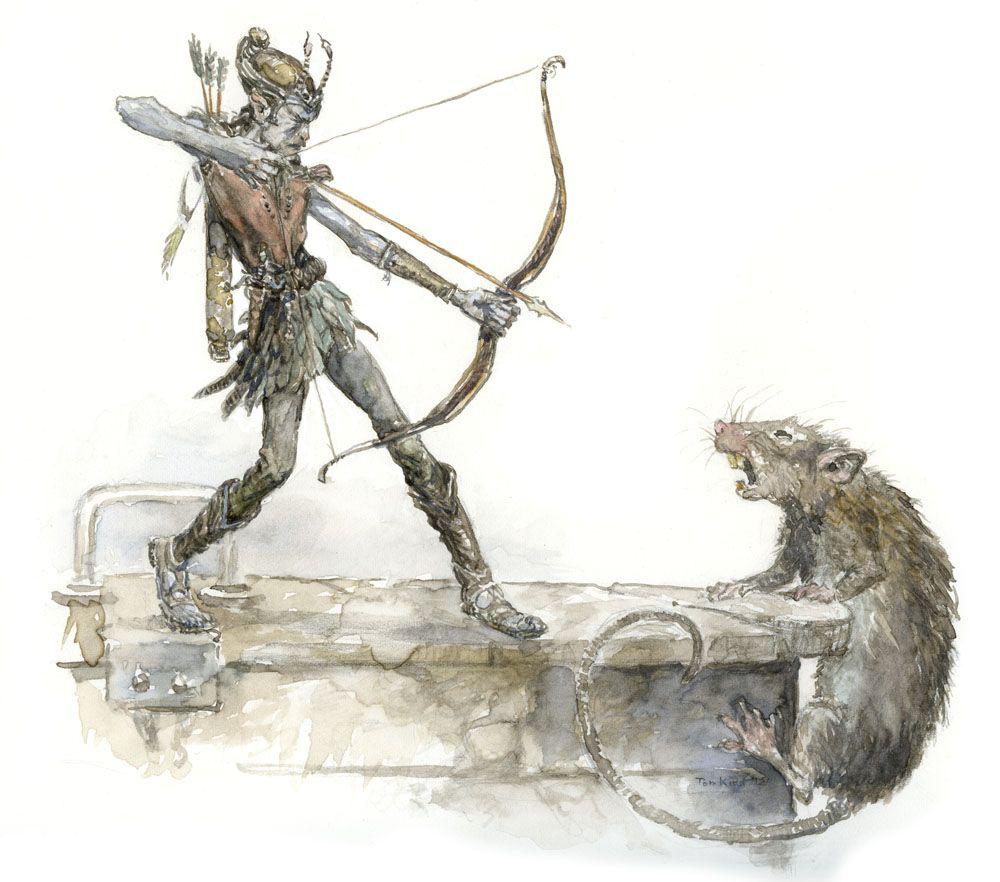

Around the well, the silent slaughter of the night before had been repeated. The archers on the well cap were unstringing their bows as the butchers moved out to the skewered rats. It seemed to her that there were far more pecksies tonight. “Don’t you fear that you’ll run out of rats?” she asked.

“Drought will bring rats here. The well and your stored grain draw them.” The pecksie gave her a sideways look. “But for us, rats would have eaten all grain. You should not be stingy if we take an egg sometimes.”

Mirrifen bit back a retort and lifted the well hatch. The bucket’s rope played out longer than it ever had. She said quietly, “If the drought lasts much longer, the well will go dry.”

The pecksie didn’t look at her. “You waste words on what you can’t change.”

Mirrifen drew the bucket up slowly. Every bucket of water she gave to the pecksie was one less bucket for Jamie and her. Mirrifen braced her courage and asked the question. “If I told you to leave our farm and take the other pecksies with you, you would have to do it.”

The pecksie didn’t answer the question. Instead she said, “You bound me to see that no harm comes to the child. To fulfill that, I must be where the child is.” She stared off into the darkness. “Or the child must be where I am.”

A chill went up Mirrifen’s back. As she brought the brimming bucket to the surface, the pecksie said in a flat voice, “Thank you for the water, mistress. I am bound.”

In less than a heartbeat, pecksies surrounded the bucket. The pecksie’s fluting voice was stern, and they formed an orderly line. The water was rationed, each creature drinking for only a few seconds before another took his place. Nonetheless, Mirrifen drew four buckets of water before the horde was satisfied. The hatch thudded shut. The pecksie hunters dispersed. Her pecksie was the last to leave, walking not into the fields, but toward the house.

Slowly Mirrifen followed her. The house was silent. Inside the darkened bedroom, she sat down on the hard chair. She saw no pecksies, but knew they were there. The pecksie had said rats couldn’t get into the room but there seemed no way to keep pecksies out.

She awakened late the next morning to Jami shaking her shoulder. “You slept! You promised to guard me, and then you slept!”

Sunlight flooded the room. The morning chores awaited and her head pounded from weariness. “I did my best. Please, Jami. Don’t be angry. Nothing bad happened.”

“Is this ‘nothing bad’? What is this thing?”

Jami’s thrust a hedge-witch charm at her. The amulet was smeared with silver but with a lurch of her heart, Mirrifen recognized beads and spindles from her own supplies. “I found it on top of me, right on my belly. The baby woke me, squirming inside me. He’s never moved like that before!” She stared at Mirrifen and demanded, “Did you make this? What is it?”