Words Can Change Your Brain (4 page)

Read Words Can Change Your Brain Online

Authors: Andrew Newberg

We suggest that you spend five or ten minutes each day practicing the different components of Compassionate Communication, first with the people you trust the most, and then with other people in your social and business circles. After a few weeks of practice, you should notice a significant difference in how you relate to others and how they respond to you, even though they may be unfamiliar with the principles you are applying. Ask them if they notice any difference in your communication style. They’ll probably pause for a few moments and agree, and in that instant you

will have successfully introduced Compassionate Communication to them. You’ll generate greater empathy and mutual trust simply by using your words more wisely.

C

HAPTER 2

The Power of Words

W

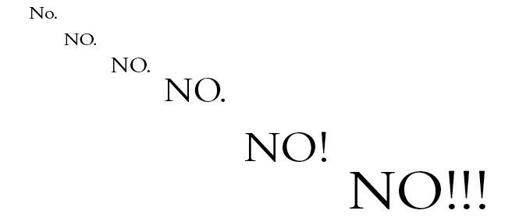

ords can heal or hurt, and it only takes a few seconds to prove this neurological fact. First ask yourself this question: how relaxed or tense do you feel right now?

Next become as relaxed as you possibly can. Take three deep breaths and yawn a few times; this is one of the most effective ways to reduce physical, emotional, and neurological stress.

Now stretch your arms above your head, drop them to your side, and shake out your hands. Gently roll your head around to loosen up the muscles in your neck and shoulders, then take three more deep breaths. Check your body: do you feel more relaxed or tense? Now check your mind: do you feel more alert or tired or calm?

You’ve just engaged in the first strategy of Compassionate Communication. Later we’ll explain how these small actions change your brain and promote more effective dialogue with others. But for this experiment, we want you to stay as relaxed as possible so you can notice the subtle emotional shifts that take place when you see the first series of words on the following page. Take another deep breath and bring your awareness into the present moment. When you are ready, turn the page.

How did you react when saw those words? Did your eyebrows rise? Did your muscles tighten? Did you smile or tense your face?

If you were in an fMRI scanner—a huge doughnut-shaped magnet that can take a video of the neural changes happening in your brain—we would record, in less than a second, a substantial increase of activity in your amygdala and the release of dozens of stress-producing hormones and neurotransmitters. These chemicals immediately interrupt the normal functioning of your brain, especially those that are involved with logic, reason, language processing, and communication.

And the more you stay focused on negative words and thoughts, the more you can actually damage key structures that regulate your memory, feelings, and emotions.

1

You may disrupt your sleep, your appetite, and the way your brain regulates happiness, longevity, and health.

That’s how powerful a single negative word or phrase can be. And if you vocalize your negativity, even more stress chemicals will be released, not only in your brain, but in the listener’s brain as well. You’ll both experience increased anxiety and irritability, and it will generate mutual distrust, thereby undermining the ability to build empathy and cooperation. The same thing happens in your brain when you listen to arguments on the radio or see a violent scene in a movie. The brain, it turns out, doesn’t distinguish between fantasies and facts when it perceives a negative event. Instead it assumes that a real danger exists in the world.

Any form of negative rumination—for example, worrying about your financial future or health—will stimulate the release of destructive neurochemicals. And if you are prone to constantly thinking about negative possibilities and persistently ruminating about problems that have occurred in the past, you may ultimately test positive for clinical depression.

2

The same holds true for children: the more negative thoughts they have, the more likely they are to experience emotional turmoil.

3

But if you teach them to think positively, you can turn their lives around.

4

Negative thinking is also self-perpetuating: the more you are exposed to it—your own or other people’s—the more your brain will generate additional negative feelings and thoughts. In fact, the human brain seems to have a capacity to spend more time worrying than that of any other creature on the planet. And if you bring that negativity into your speech, you can pull everyone around you into a downward spiral that may eventually lead to violence. And the more you engage in negative dialogue, at home or at work, the more difficult it becomes to stop.

5

Fearful Words

Angry words send alarm messages through the brain, and they partially shut down the logic-and-reasoning centers located in the frontal lobes. But what about fearful words—words like “poverty,” “sickness,” “loneliness,” and “death”? These too stimulate many centers of the brain, but they have a different effect from negative words. The fight-or-flight reaction triggered by the amygdala causes us to begin to fantasize about negative outcomes, and the brain then begins to rehearse possible counterstrategies for events that may or may not

occur in the future.

6

In other words, we overtax our brains by ruminating on fearful fantasies.

Curiously, we seem to be hardwired to worry—perhaps an artifact of ancient memories carried over from ancestral times when there were countless threats to our survival.

7

However, most of the worries we have today are not about really serious threats. We can learn how to retrain our brain by interrupting these negative thoughts and fears. By redirecting our awareness to setting positive goals and building a strong, optimistic sense of accomplishment, we strengthen the areas in our frontal lobe that suppress our tendency to react to imaginary fears. Not only do we build neural circuits relating to happiness, contentment, and life-satisfaction, we also strengthen specific circuits that enhance our social awareness and our ability to empathize with others. This is the ideal state in which effective communication can prosper.

Interrupting Negative Thoughts and Feelings

Several steps can be taken to interrupt the natural propensity to worry. First ask yourself this question: is the situation

really

a threat to my personal survival? The answer is almost always no. Our imaginative but unrealistic frontal lobes are simply fantasizing about a catastrophic event.

The next step is to reframe a negative thought into a positive one. Instead of worrying about your financial situation—which won’t have any effect on your income—think about the ways that you can

generate more money and keep your mind focused on the steps you need to take to achieve your financial goals.

The same holds true for personal relationships. For example, if you are the type of person who worries about being rejected or perceived in the wrong way by others, shift your focus to those qualities that you truly admire about yourself. Then, when you talk to others, talk about the things you really love and deeply value. And don’t talk about your personal problems or the catastrophes happening in the world; they’ll enmesh you in feelings of self-doubt and insecurity.

The faster we can interrupt the amygdala’s reaction to real or imaginary threats, the quicker we can generate a feeling of safety and well-being and extinguish the possibility of forming a permanent negative memory in our brain.

8

By shifting our language from worry to optimism, we maximize our potential to succeed at any realistic goal we truly desire.

Words Shape the Reality We Perceive

Human brains like to ruminate on negative fantasies, and they’re also odd in another way: they respond to positive and negative fantasies as if they were real. Moviemakers make use of this phenomenon all the time. When the green three-eyed monster jumps out of the closet, we jump out of our seat. This is what makes nightmares so frightening for children, whose brains have yet to develop clear distinctions between language-based fantasies and reality.

To make matters worse, the more emotional we get, the more real the imaginary thought becomes. But imagination is a two-way street. If you intensely focus on a word like “peace” or “love,” the emotional centers in the brain calm down. The outside world hasn’t changed at all, but you will still feel more safe and secure. This is the neurological power of positive thinking, and to date it has been supported by hundreds of well-designed studies. In fact, if you simply practice staying relaxed, as we asked you to do at the beginning of this chapter, and repetitively focus on positive words and images, anxiety and depression will decrease and the number of your unconscious

negative thoughts will decline.

9

When doctors and therapists teach patients to reframe negative thoughts and worries into positive affirmations, the communication process improves and the patient regains self-control and confidence.

10

Indeed just seeing a list of positive words for a few seconds will make a highly anxious or depressed person feel better, and people who use more positive words tend to have greater control over emotional regulation.

11

Growing Positivity

Certain positive words—like “peace” or “love”—may actually have the power to alter the expression of genes throughout the brain and body, turning them on and off in ways that lower the amount of physical and emotional stress we normally experience throughout the day.

12

But these types of words cannot be grasped by a child’s immature brain. Young children do not have the neural capacity to think in abstract terms, so the first words they learn are associated with simple, concrete images and actions. Verbs like “run” or “eat” can be easily associated with visual images, but abstract verbs like “love” or “share” demand far more neural activity than a young child’s brain can muster.

13

Even more neural processing is required when it comes to highly abstract concepts like “peace” or “compassion.” This is easy to test. See how long it takes you to visualize the word “table.” In less than a second, you can grasp its shape and function, and you can see it in your mind’s eye. Now think about the word “justice.” You’ll realize that it takes much longer to identify an image, and most people will envision the well-known picture of a woman holding a scale. Obviously justice is far more complex than that image can impart, which explains why so few people can agree on what this important concept means. Abstract words make greater demands on many areas of the brain,

14

whereas concrete words require less neural activity.

Abstract thoughts may be essential for solving complex problems, but they also distance us from deeper feelings, especially those that are needed to bind us to other people. In fact, some people can become so involved with abstract concepts that they partially lose touch with reality.

15

Love is a perfect example because we can easily project our ideal notions onto a potential partner, thereby blinding ourselves to the other person’s faults. Why does it take so many years to discover what love actually is? Neuroscience has an answer: love turns out to be expressed through one of the most complicated and complex circuitries identified in the human brain.

16

Thus the

language

of love may be the most sophisticated communication process of all.

Abstract concepts can also be sources of miscommunication and conflict because we rarely explain to others what these complex terms mean to us. Instead we make the mistake of assuming that other people share the same meanings that we have imposed on our words. They don’t. Let’s take, for example, the word “God.” In our research we queried thousands of people, using a variety of surveys and questionnaires, and discovered that 90 percent of the respondents had definitions that differed significantly from everyone else. Even people who came from the same religious or spiritual background had fundamentally unique perceptions of what this word means. And for the most part, they never realized that the person they were talking to about God had something entirely different in mind.

Our advice: when an important abstract concept comes up in conversation, take a few minutes to explore what it means to each of you. Don’t take your words, or the other person’s, for granted. When you take the time to converse about important values and beliefs, clarifying terms will help both of you avoid later conflicts and confusion.

The Power of Yes

What about the power of the word “yes”? Using brain-scan technology, we now have a very good idea of what happens when we hear positive words and phrases. What do we see? Not much! Positive words do not connote a threat to our survival, so our brain doesn’t need

to respond as rapidly as it does to the word “no.”

17

This presents a problem because evidence showing that positive thinking is essential for developing healthy relationships and work productivity continues to grow.