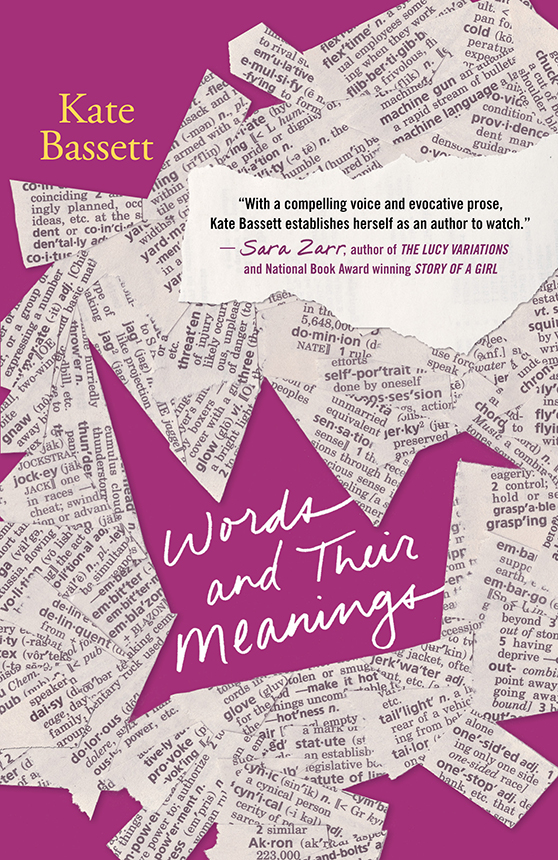

Words and Their Meanings

Read Words and Their Meanings Online

Authors: Kate Bassett

Tags: #teen, #teen lit, #teen reads, #teen novel, #teen book, #teen fiction, #ya, #ya fiction, #ya novel, #ya book, #young adult, #young adult novel, #young adult book, #young adult fiction, #words & their meanings, #words and there meanings, #words & there meanings

Woodbury, Minnesota

Copyright Information

Words and Their Meanings

© 2014 by Kate Bassett.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any matter whatsoever, including Internet usage, without written permission from Flux, except in the form of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

As the purchaser of this ebook, you are granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this ebook on screen. The text may not be otherwise reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, or recorded on any other storage device in any form or by any means.

Any unauthorized usage of the text without express written permission of the publisher is a violation of the author's copyright and is illegal and punishable by law.

This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents are either the product of the author's imagination or are used fictitiously, and any resemblance to actual persons living or dead, business establishments, events, or locales is entirely coincidental.

Cover models used for illustrative purposes only and may not endorse or represent the book's subject.

First e-book edition © 2014

E-book ISBN: 9780738741048

Cover design by Ellen Lawson

Back cover image © iStockphoto.com/15492447/@akiyoko

Flux is an imprint of Llewellyn Worldwide Ltd.

Flux does not participate in, endorse, or have any authority or responsibility concerning private business arrangements between our authors and the public.

Any Internet references contained in this work are current at publication time, but the publisher cannot guarantee that a specific reference will continue or be maintained. Please refer to the publisher's website for links to current author websites.

Flux

Llewellyn Worldwide Ltd.

2143 Wooddale Drive

Woodbury, MN 55125

www.fluxnow.com

Manufactured in the United States of America

To Justin,

for redefining all the most important

words in our story.

1

I

can't hold my breath for the full nineteen minutes. I made it to three minutes once, but then I passed out. Instead, I have to settle for statue stillness and bulging my eyes wide enough to hurt. Coffin yoga has a lot of rules, but I think the no-blinking part is most important. Pupils should show during the open casket experience.

Case in point: my Uncle Joeâwho was more like my brother, right down to sleeping in the room across the hall until he went to collegeâdied last year. He was nineteen. He got laid out in a pine box about the size of my twin bed. His eyes were closed and his smile was fake. My last image of him is dominated by powdered eyelids and a bad smirk.

And that sucks.

“Anna?” My grandfather's voice echoes up the stairs. It's a mix of sandpaper and gravel. I listen until he reaches my bedroom door, knocks once, and repeats, “Anna?”

I can't answer. Corpses don't talk and I've only been at this for 2.5 minutes. That means I've got 16.5 to go, so Gramps will just have to keep standing there, thinking whatever it is he thinks about the immature, irrational shell of his once-brilliant granddaughter.

Damn it. I've lost concentration.

Now my nose itches.

“Anna? Are you doing that thing again? That thing your mother asked you to please stop doing?”

He could just walk in and see for himself. The first time Mom caught my mid-morning ritual, she thought I was dead for real. Took the door right off the hinges for a few weeks. When I finally got my door back, it was sans lock.

Crap. I blinked.

“Your mom had to go out and she didn't want you guys alone, so I came over early. I'm going to make breakfast for Bea. When I come back, you need to be up. And ready for the day.”

Gramps doesn't elaborate, but I know Mom went to Joe's grave. And she went early because she's afraid of running into my dad. Right before he moved out, he said the one thing he can never take back: “The loss is less yours. Joe didn't share your blood.” As if he could cut the strings of attachment from raising a child as her own for seventeen years.

I've still got one minute to go when Gramps returns. This time, he doesn't bother knocking.

His skin is Silly Putty and his walk is a little lopsided. But he's still a strong force and I feel him here, without looking. I wonder if his expression is sad. I wonder if he recognizes the blankness in my face.

Gramps has a dog named Morte, who happens to be a very dead stuffed German shepherd my grandmother bought at one of the garage sales she was famous for raiding. The dog has glass-black eyes and stares into the abyss and at people with the exact same intensity. It's the look I'm aiming to recreate. It's real. Morticians could take a lesson from taxidermists.

Thirty seconds to go.

The shrinks all want to talk about coffin yoga. They can't fathom the way some people have no rhyme or reason to their mourning. How maybe there are more ways to grieve than the stupid five steps outlined in their colorful pamphlets. Next time I see my new doc, I'll probably tell her I'm adding a no-thinking rule into coffin yoga. She'll ask what it might symbolize. And I'll glare at her ridiculous red-rimmed glasses and flowing tunic. I'll speak slow and clear, so she might understand there's nothing representative about this. My mind just needs the break.

Because:

That crack in the ceiling looks like a vein.

Maybe I should freak Mom out and paint the crack red.

It would almost look like a giant river of blood.

She'd have to call my dad and they'd fight when he showed up.

Maybe I'd let a real river of blood flow down the stairs while waiting.

What would Joe think of my imagination moonlighting as a total psychopath?

He'd laugh and remind me about my six-year obsession with Care Bears.

Love-a-Lot Bear. Good Luck Bear. Funshine Bear.

Wonder if those stuffed fluff-balls are buried in a box in the basement.

Bet they're all mildewed and moldy.

Gramps is starting to smell like mold.

I don't like it. Makes me think of why people get put in coffins in the first place.

Dead people.

Joe is a dead person.

Joe is a dead person because of me.

365 days later, those words still don't seem real.

Time's up.

I curl into myself for a second before swinging my legs over the side of the bed. Gramps sighs and sits down beside me.

“Good morning, sunshine. Seems like a good day to ⦠”

He lets his voice trail off, willing me to finish the sentence.

I don't. Instead I wipe my eyes with the back of my hand and walk over to my white wicker desk. I got it at age eleven, back when things like pastel flowers and T-shirts with rainbows were all the rage. It's where I do part two of my morni

ng ritual: write my daily verse.

“Lookâthe yoga⦔ I pause, motioning back to my bed/coffin. “I get how Mom thinks it's crazy. I know the therapists think I'm trying to âbury my emotions.' But this is me. This is the way I deal with it.”

Gramps looks at me. The weight of the day, of what I'm supposed to do now, it makes me itchy and reckless. I know what I'm risking. Right now, I don't care. I keep talking.

“Why is it such a big deal anyway? I've done some form of yoga since ninth grade. I've only changed how I practice. I mean, maybe this will catch on as a whole new style. Maybe I'll actually achieve Medusa-like stone stillness and I'll make DVDs and get super rich. Wonder what the therapists would say then.”

He looks at the ceiling, shakes his head.

I open my laptop. I slam it shut. I stare at my mother's father, daring him.

“I love you,” he says.

There's no judgment. No disappointment. No accusation. I wait for more, but Gramps stands up and pats my hand. His fingers shake a little. I hold them tight, but I'm also the first to let go.

“Come downstairs in a minute.”

I nod.

Stepping toward the hall, his back already to me, Gramps pauses.

“Did you know I've started working on a project?” he asks. “It's a surprise. I hope you'll see it as a gift. I've been working on it downstairs all morning. And if that doesn't spark any interest, how about bribing you out of your room with a new origami design? Maybe I can teach you to fold a Yoda? You could tape him to the top of your laptop and get the lowdown on secrets of the universe. âBetter it will get, when trust the force, you do.'”

There's no way I can oblige him with a giggle or a smile, so I just nod again while reopening my laptop. I don't want his hope. I don't want to see myself the way he may still picture me. And I don't need his gentle reminders.

Joe's one-year deadaversary is supposed to mark the end of my period of mourning, as promised to shrink number nine, my parents, and my best friend, Nat.

But what are promises, really? Nothing but words.

Daily Verse:

We're all made up of opposites, and they often crucify us.

2

I

used to have a matching oval wicker mirror above my desk. It's been replaced by a grid of photos, ripped out of magazines or printed off websites. The images are all the same girl. In the pictures, she'll be frozen forever at age twenty. Three years older than me. One year older than Joe. She's got stringy, wild black hair. Mostly, she's wearing white tank tops or dirty T-shirts and ripped-up jeans. Her chest is draped with handmade talismans or skinny suspenders. A girl who never smiles but stares at the camera with eyes like dark pools, like a nighttime lake waiting to pull you in, under.

Patti Smith in 1973. Go ahead. Google it. I'm a carbon copy.

Like practically everyone else in my generation who's grown up on shitty boy bands and reality shows, I'd never even heard of Patti Smith until 364 days ago. It took me exactly two weeks, one day, and six or so hours to slip into her skin. Not sleeping made it easy to match her sunken sockets and dark circles. My muddy brown hair, hacked chunky to my shoulders (or forehead or neck, depending on where you're looking), is now the color of spilled ink. It's fried from constant use of a straightening iron. My wardrobe imitates those feral images of a girl on the edge.

Beyond looks, here's a crash course in Patti Smith: she's an indisputable rock-and-roll legend. A captor of light and dark. People call her the Godmother of Punk, but she's so much more. She's the embodiment of a creative soul.

I can't sing. I pull in tons of dark but zilcho light, and I'm not exactly a legend or a godmother of any variety. Also, whatever soul I might have possessed flew out the window a year ago.

But Patti Smith was a poet before anything else. That's all I needed. A poet whose words could replace my own.

I discovered her in an old

Esquire

clip tucked in a hospital room drawer. Her attitude and stories and philosophies were magnets, drawing my fragmented pieces together again. I begged until a nurse gave in and snuck me my phone for supervised downloading of a bunch of Patti's music. Which led to dancing on a table as soon as the prefix “un” attached itself to “supervised.” Which, of course, led to a four-point lockdown.

But that's another story.

My daily verse comes from Patti, always. Every morning, after exactly nineteen minutes of coffin yoga, I come over to my desk and wipe away the shadow of yesterday's verse with a baby oil-soaked cotton ball (today that was

“

I have my dead and I live with them”

).

I find a lot of daily verses on Twitter, which seems to be the Internet's most formidable source of Patti's braindumps. Her thoughts are puncture wounds when jabbed into 140 characters or less.

Sometimes I scroll through a thousand duds before finding the right phrase, the right tone to set for my day. Those mornings are the worst. I lose focus on her words, instead remembering a time when my own thoughts got scribbled across my arms, legs, hands.

Joe used to tease my mother, his sister-in-law turned mom after his own parents died. He claimed I'd end up with a thousand real tattoos someday, because I like to write on myself so much. Mom responded with Oscar-worthy grimaces, even though everybody knew my scribbles only stayed on skin until I could transfer them to paper. I always kept a marker in my pocket in case I saw a sunset yolk break just so across the river, or overheard a conversation I knew had to be reinvented inside one of my stories.

“

You could carry a little notebook, like normal people,” Joe would say w

ith his lopsided grin.

“But then I'd be normal,” I'd reply, jaw dropping in mock horror.

Every so often, just when my ink started to run dry, a new Sharpie would appear on my desk.

Markers last a lot longer now. And the words on my skin are stolen from someone stronger. Today's only took six seconds to find. The first sentence I read reached into my gut. A renegade sob clawed up my throat. I swallowed again and again before pushing the black tip into my skin.

“We're all made up of opposites, and they often crucify us.”

Joe loved human psychology. His favorite course freshman year, he'd come home from Ann Arbor and sit in my room explaining all hierarchies of need and personal myths and contradictions between ego and self. But he never told me how I could love and hate writing. Or how dependency can lead to so much loss.

And then he died.

And I lost my words.

And everything, everything fell apart.

Today's verse is war paint. I etch each letter inside my arm, between wrist and elbow, with bold marker strokes.

I trace the word CRUCIFY so many times, the letters don't move, even when I clench my fist.