Wonder Woman Unbound (38 page)

Read Wonder Woman Unbound Online

Authors: Tim Hanley

A lot of Potter’s proposal was used, and he stayed on the new series as scripter and co-plotter for a few issues, but

Wonder Woman

soon became Pérez’s book. While he’d only planned to help launch the series and stick around for six months or so, Pérez ended up staying on the book for five years.

Pérez’s new origin story for Wonder Woman had a framework that was similar to her Golden Age origin and retained a feminist message, but it was also more involved. The story began in 1200

BCE,

when the Olympian goddesses finally had enough of the constant war and violence of mankind. They proposed a new female race of humans who would be “strong … brave … compassionate” and set an example for the rest of mankind. Ares, the god of war, was fiercely opposed to this because all of his power came from mankind worshipping war. Ultimately, Zeus refused to pick a side and the female goddesses, with the help of Hermes, set about creating the Amazons.

They journeyed deep into Hades to the womb of Gaea, the mother of the Earth itself. In this most secret part of Hades, Gaea had hidden the souls of women who had been killed by men, their lives cut short by violence and hatred. Artemis released the souls and they became the Amazons, bursting forth as fully formed women in a new land. Hippolyte was the first to emerge, and she became their queen. The newly born Amazons were visited by the goddesses, who told them that they were a “sacred

sisterhood

,” a “

chosen race

—born to lead humanity in the ways of

virtue

.”

Then came Hercules, goaded on by an irate Ares. Hercules tricked the Amazons, they were captured, Athena freed them, and they left for a new home far away from the world of men. The Amazons hadn’t succeeded in their mission to change the world, but the goddesses were playing a long game. Something great would come from the Amazons.

The bearer of Hippolyte’s original soul was pregnant when she died, and so the queen felt a yearning for a daughter. The oracle of the Amazons told her to form a baby out of clay and then “open yourself to fair

Artemis

—that the

mid-wife of all Olympus

may enter you.” There was one soul remaining in the womb of Gaea, specially saved for this moment, and it gave life to the clay baby. The goddesses also granted the baby gifts: power and strength from Demeter, great beauty and a loving heart from Aphrodite, wisdom from Athena, the eye of the hunter and unity with beasts from Artemis, “sisterhood with fire—that it may open men’s hearts to her” from Hestia, and Hermes gave her speed and flight. The baby was named Diana, and she soon became the champion of the Amazons.

Borrowing the Hercules story and the clay from Marston and the gods bequeathing powers from Kanigher, Pérez continued the post-Marston trend of Diana being unique among the Amazons but he also made the goddesses the source of the majority of her powers. The Pérez origin was a hybrid, referencing the past with an eye to the future.

Soon grown, Diana won a tournament in disguise and became Wonder Woman, saved Steve Trevor and returned him to America, and then she saved the world from a great evil, but these familiar elements had new twists. Steve was older, a pilot near retirement age forced to fly a secret mission by a cult of Ares that had gained power in the American military. Ares, still upset about the Amazons, was about to start World War III and wanted to eliminate the champions of the goddesses who would oppose him. Steve unknowingly flew the secret passage to Themyscira, the home of the Amazons, and his possessed copilot tried to blow up the island. Not surprisingly, Wonder Woman lassoed the missile, saved Steve, and, once she arrived in America, foiled Ares’s master plan.

She did so with a new supporting cast. Etta Candy was a lieutenant in the air force, a nod to her military role in the TV show, and Etta and Steve soon became a couple. Wonder Woman’s main companion was Julia Kapatelis, a professor of Greek history at Harvard, and her teenage daughter, Vanessa. They became her surrogate family in America. Wonder Woman also had a publicist, Myndi Mayer, who helped her establish herself and her message of peace and compassion in the world of men.

The Amazons were more fleshed out as well, with characters like Epione the healer, Hellene the historian, Menalippe the oracle, Philippus the captain of the guard, and many more. Themyscira was no longer a generic all-female utopia; it housed women with varied personalities and different ideas of the Amazons’ role in the world. This came to a head when Wonder Woman wanted to open up Themyscira to the rest of the world. There was much debate, and it came to a vote. The majority decided to rejoin the world, and the isolationism of past incarnations of the Amazons ended. Instead of barricading themselves to maintain some sort of superiority and purity, they became part of the world again. Themyscira welcomed visitors, male and female, and Hippolyte even traveled to the United Nations to speak.

Wonder Woman faced challenges from patriarchal forces, both mortal and divine. She spent most of her time battling rogue gods and mythological beasts, but Pérez kept the series planted firmly in the real world and he tackled some heavy topics. Myndi Mayer died of a drug overdose, and an issue explored alcohol and drug abuse. In another issue, Vanessa’s cheery friend Lucy Spears committed suicide, and the book dealt with depression and the loss of a loved one. Wonder Woman’s human friends kept the series grounded and relevant to a modern audience.

Wonder Woman

was also notable for its many female creators. Janice Race developed the book before handing the editorial duties to Karen Berger, who remained editor for Pérez’s entire run.

*

Women were involved in

Wonder Woman

at every level while Berger was in charge. Mindy Newell cowrote twelve issues with Pérez, while Jill Thompson penciled most of the last third of Pérez’s tenure and did occasional covers. When Thompson needed a breather, Colleen Doran and Cynthia Martin took over illustration duties. Tatjana Wood did the coloring for the early issues of the book, and Nansi Hoolahan was the regular colorist by the end of the Pérez era.

While the Pérez relaunch is well regarded, the book wasn’t without its problems. The series continued the depiction of Wonder Woman as an unattainable ideal, and other female characters weren’t empowered by knowing Wonder Woman so much as they felt bad about themselves in comparison. For example, Vanessa was concerned her boyfriend wouldn’t like her anymore once he got a look at Wonder Woman, and Wonder Woman’s lithe figure made Etta Candy feel sensitive about her weight.

Nonetheless, the Pérez era revitalized Wonder Woman, however briefly. He combined elements of her Golden and Silver Age past into a new, modern take on the character that retained her feminist leanings and also established Wonder Woman as a champion of global peace and cooperation. For the first time in decades, Wonder Woman was relevant and the book was selling well. This didn’t last for long.

Background Player

After George Pérez left

Wonder Woman

in the early 1990s, the series remained stagnant for the next two decades. William Messner-Loebs replaced Pérez as writer and took Wonder Woman in a new direction. She became a space pirate for a while, then got a job at the Mexican fast food restaurant Taco Whiz when the Amazons disappeared and left her homeless.

Messner-Loebs was soon joined by artist Mike Deodato Jr., whose style sexualized the book. Wonder Woman had impossibly long legs, a minuscule waist, breasts that jutted out like torpedoes, and a perpetual sexy glare. She and her fellow Amazons were always positioned so as to best emphasize their features, and Wonder Woman’s briefs turned into a painful-looking thong that pulled up past her waist, while Hippolyta wore what can only be described as dual breast hammocks. Deodato’s artwork was a far cry from Pérez’s more classic, tasteful style.

John Byrne took over as writer and artist after Messner-Loebs left and largely ignored everything that had happened before. He moved Wonder Woman to the fictional Gateway City, gave her a new supporting cast, and even killed her for a few issues. The book wasn’t terrible, but nor was it particularly good. By the mid-1990s, the series had settled into a middling quality with middling sales, and it never came back in any lasting way.

There were some good moments: Phil Jimenez’s run on the book as writer and artist is very well respected; writer Greg Rucka was twice nominated for an Eisner, the comics industry’s biggest award, while writing

Wonder Woman;

and Gail Simone became the series’ first regular female writer.

*

There were occasional sales jumps, but they quickly petered out. Another relaunch in 2006 lit up the sales charts briefly, but delays and a tie-in to

Amazons Attack,

a poorly executed miniseries in which the Amazons invaded America, soon dragged the book down. When

Wonder Woman

was renumbered to mark its 600th issue overall, J. Michael Straczynski came onboard as writer and sales rose initially until Straczynski abruptly left the book. Then sales plummeted again.

DC Comics often refers to Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman as its “Big Three” or the “Trinity,” its three heroes who have been around the longest and are most well known. However, while Wonder Woman spent most of the Modern Age trucking along in the middle of the pack with her one series, the men were much busier. Batman and Superman didn’t just have their own starring books; they were a brand. Along with their own titles, their sidekicks and associates had titles of their own, all tagged with the bat symbol or the S-shield to show they were part of a larger family of books. Wonder Woman just had

Wonder Woman

.

†

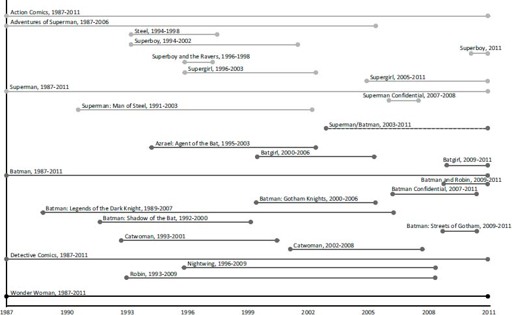

The chart on the next page shows a timeline of select ongoing series that starred or were closely related to the Big Three.

‡

Wonder Woman costarred in Justice League books and is involved in big, line-wide events with everyone else, but she and her supporting cast have only had one book of their own for the entire Modern Age while Superman, Batman, and their many associates have had scads of titles. Wonder Woman hasn’t been a priority at DC, and so she’s faded into the background.

Part of this is due to a lack of iconic stories. Batman has books like Frank Miller’s

Batman: Year One

and

The Dark Knight Returns

that invigorated Batman in the late 1980s, and later books like

The Long Halloween

and

Hush

that continue to sell well. Superman has classic shorter stories from the 1980s, like Alan Moore’s “Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow?” and “For the Man Who Has Everything,” along with later successes like

Superman for All Seasons

and

All Star Superman.

All of these books have been reprinted in various editions over the years, and the Batman and Superman sections in bookstores are always jam-packed.

Wonder Woman doesn’t really have any iconic stories. The Pérez issues were collected once, and her new issues come out as graphic novels twice a year, but those don’t stay in print for long. One of her only standalone graphic novels, Greg Rucka and J. G. Jones’s

Wonder Woman: The Hiketia,

was a critical success in 2003, but it’s out of print now too. Wonder Woman’s back catalog is very thin. In May 2013, DC Comics put out the

DC Entertainment Essential Graphic Novels and Chronology 2013

guide, a comprehensive handbook of its extensive backlist catalog. Batman had eighty-four titles listed and Superman had fifty-three, while lesser-known heroes like Green Lantern and the Flash had forty-six and fifteen titles, respectively. The Wonder Woman section listed only six titles.

Batman and Superman have also had huge event stories that were key moments in the DC Comics universe. The villain Bane broke Batman’s back in

Knightfall,

and that story along with Batman’s return has been a touchstone for Batman comics since. Furthermore, Bane became a regular villain in the DC universe, and he and the breaking of Batman were a key part of the blockbuster movie

The Dark Knight Rises.