Women and Children First (44 page)

Reg and Florence got married a week before Christmas 1912 and their first child, a daughter, was born a year later. By that time Reg’s ‘New York Café’, in central Southampton, was a roaring success. He was thinking of opening another branch when war broke out in August 1914, and the following month he enlisted. In 1916, he was awarded a Distinguished Conduct Medal for his outstanding bravery at the Battle of the Somme, but shortly afterwards he received a serious leg injury that meant he could no longer fight and he spent six months in hospital receiving painful treatments before he could walk again. Florence helped him to reopen the New York Café in 1918 and, riding on the wave of enthusiasm for all things American that prevailed after the war, he was able to open two further branches in the South of England. A son was born in 1920 and Reg called him John, after the friend he’d lost on the

Titanic

, the friend he would never forget.

Juliette and Robert tried hard to make their marriage work but she struggled with homesickness and spent ever longer periods with her own family. They never divorced but he took a mistress in New York, while Juliette raised her son back in Gloucestershire and devoted herself to her horses.

Annie and Seamus had two more children, a boy and a girl. Patrick thrived at school in America and became an office worker, the destiny his mother had always dreamed of for Finbarr. Despite many requests during the Great War, Annie no longer attempted to contact the spirits. Her embroidery was renowned in fashionable New York society and she was kept busy with that, and the demands of her expanding family.

Venetia Hamilton married an Italian count in June 1913 and set up home in his castle in northern Italy, where she held frequent house parties for titled expats. She and her husband argued fiercely over her extravagance, and both took lovers. They never had a child together, but he had a string of illegitimate children.

George Grayling had a stroke in 1915, while sitting in his library with a glass of cognac. He was paralysed down one side and lived for six months in a rest home before succumbing to a fatal bout of pneumonia.

The

Titanic

set sail from Southampton on the 10

th

of April, 1912, made brief stops in Cherbourg, France, and Queenstown, Ireland, then headed across the North Atlantic towards New York on a voyage that should have taken six days. She carried 1,322 passengers and 885 crew, who marvelled at the state-of-the-art amenities. All the descriptions of the ship in this novel are factual: there was a swimming pool, libraries, a squash court, a café with real palm trees, chandeliers and mosaic-lined Turkish baths. The décor and food were sumptuous, with no expense spared. But they only had space in the lifeboats for less than half of those on board.

The passengers included several American millionaires, including John Jacob Astor, Benjamin Guggenheim, Isidor Straus (who founded Macy’s department store in New York) and George Widener (a banker and owner of a street-car company in Philadelphia). There were British aristocrats, including Lord and Lady Duff Gordon (she owned the fashion house Maison Lucille) and the Countess of Rothes (who later helped to row her own lifeboat). And there were travellers of many different nationalities, from Eastern and Western Europe, North and South America, Japan, Russia, Australia and South Africa.

They took a northern route across the Atlantic, which was prone to icebergs in spring when glaciers in Greenland were melting. During Sunday, 14

th

April, Captain Smith received several warnings of ice ahead but he ordered his officers to keep to a speed of around 22 knots, trusting the lookouts to spot any icebergs and his officers to steer around them. However, it was a moonless night and the sea was dead calm, so there were no tell-tale ripples in the water around the huge iceberg that loomed seemingly out of nowhere at 11.40 p.m. The lookouts rang the warning bell and Officer Murdoch ordered that the ship be turned “hard a-starboard” but it was too late. There were only 37 seconds between the lookouts’ warning and the

Titanic

’s glancing collision with the iceberg.

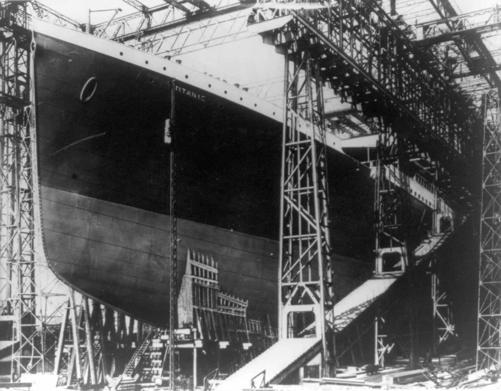

[The

Titanic

under construction in Belfast’s Harland & Wolff shipyard.]

LC-USZ 62-26743

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

The mass of ice damaged a 300-foot section of the ship’s hull, just 10 feet above the keel, and the immense water pressure caused lower compartments to flood rapidly. Officer Murdoch immediately pulled a lever that closed the watertight doors separating the ship’s bulkheads, but as the water continued to rise in the front five flooded compartments, the

Titanic

began to settle by the bow. Within twenty minutes of the collision Captain Smith realised she was going to sink, and he ordered the first “CQD” (“come quickly disaster”) message to be radioed at 12.15 a.m. then asked his officers to prepare the lifeboats.

Many passengers felt the jolt of the collision but few were alarmed. No announcement was made that the ship had only two hours to live because it was felt this would create panic. The orchestra played ragtime classics on the boat deck and drinks were still being served in the bars. Officers urged the upper classes to step into wooden rowing boats that dangled 75 feet above the ocean surface but, understandably, many were reluctant to leave the comfort of the ship. Stewards knocked on the door of first-class suites and guided their occupants to the boat deck, second-class passengers were told where to go and what to do, but most third-class passengers had to fend for themselves. Given that the layout of the ship was confusing even for crew, it’s hardly surprising that many never made it to the boat deck, and that many others arrived only after the last lifeboat had departed.

The loading of lifeboats was controversial. In keeping with the ethos of the time, the message was “women and children first”, but it wasn’t consistently applied. On the port side, Second Officer Lightoller upheld the rule strictly, only allowing sufficient men on each boat to row it. On the starboard side, Officer Lowe was more lenient, and he let men board if there were spaces remaining after all the nearby women and children had been seated. However, on both sides the boats set off with dozens of places empty. This was partly because the officers weren’t sure whether it was safe to lower a fully loaded boat from the boat deck, and partly because of the general air of confusion. By 1.55 a.m. all the lifeboats had departed, except for two “collapsibles” on the roof of the officers’ mess – but more than two-thirds of the passengers and crew were still on board.

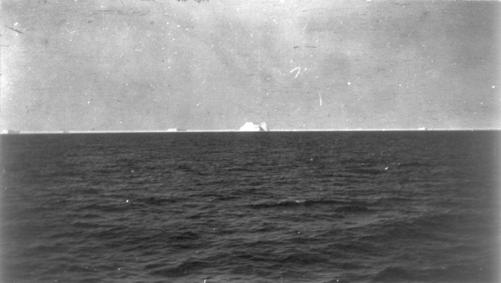

[It is thought this may have been the iceberg she struck.]

LC-USZ 62-64154

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

In the radio room, Jack Phillips and Harold McBride kept sending increasingly urgent distress messages, some of them using the new SOS call signal, but the nearest ship to respond was the

Carpathia

, and she was four hours’ sail away when she first got the message. Some people reported seeing a ship on the horizon, just around 20 miles off, and this was later identified as the

Californian

. Her radio operator had gone to bed so didn’t pick up the distress signals, and her crew couldn’t understand why rockets were being fired into the sky. Had she come to pick up

Titanic

passengers, most could have been saved.

Passengers and crew who clustered on the

Titanic

’s boat deck at 2 a.m. must have known their chances were slim, but they lined the railings trying to estimate where their best hope of survival lay. Jump too soon, while they were still too high above the ocean surface, and they would die from the impact. But it was thought that when the ship disappeared she would suck all who surrounded her underwater, so they were keen to get as far away as they could before that happened. And yet, it was imperative that they didn’t spend too long in the water, whose temperature was below freezing point. It was a tricky decision.

At 2.20 a.m. the

Titanic

’s hull split in two and her stern rose perpendicular in the air before slipping down into the ocean. Those who hadn’t already jumped were now hurled into the water and a communal howl of anguish filled the air. Doctors estimate that a fit man would only survive around 20 minutes in such water temperatures, so the clock was ticking. Their sole chance was to get into a lifeboat – and fast. But the seamen in charge of the lifeboats had rowed some distance away and were reluctant to turn back in case they were swamped by survivors trying to clamber on board, which could cause them to sink. Officer Lowe was one of the few who did go back for survivors, but only after the cries of the dying had begun to subside and he was sure they wouldn’t be overwhelmed. He picked up five survivors, of whom one subsequently died.

Meanwhile, Officer Lightoller had taken charge of a collapsible which had been washed overboard upside down in the final moments before the ship sank. He got around 30 people to stand up on it and, by directing their movements, managed to keep them afloat for the next two hours.

If all the spaces on lifeboats had been filled, it would have been possible to rescue 1,178 people, but only 711 were to survive. The experience of sitting in a lifeboat listening to 1,496 people dying in the water around you must have been devastating. Most of them perished from hypothermia, as their life preservers kept them from drowning. Passengers on the lifeboats heard them crying for help, calling out loved ones’ names, muttering prayers, and then sighing and groaning as they passed away. For the rest of their lives, no survivor could forget that awful, heart-rending sound.

It was around 4 a.m. when Captain Rostron of the

Carpathia

, one of the great heroes of the night, arrived at the

Titanic

’s last known position. He had raced there at top speed, dodging icebergs on the way, but he arrived to find just 20 lifeboats, one of them half submerged and another upside down. The

Titanic

had disappeared. His crew helped to bring survivors on board and

Carpathia

passengers donated dry clothing and even their cabins to help. For the first hours,

Titanic

survivors clung to the hope that their loved ones might yet be found, but gradually that hope faded. Captain Rostron circled the area once then turned and headed back to New York.

There was confusion about the early news that reached the rest of the world, with some papers reporting the

Titanic

was being towed to Halifax and that all were saved. Such was John Jacob Astor’s wealth that when word came through that he had perished, there were initial fears that the American stock exchange might collapse. Survivor lists were sent to shore by Marconi-gram but were filled with inaccuracies. What was known was that the

Carpathia

would dock on the evening of Thursday 18

th

April, and the pier was crowded with relatives, while photographers and journalists tried everything they could think of to gain an exclusive. The Women’s Relief Committee was on hand to look after those left destitute by the sinking, while the rich were met by their chauffeurs.

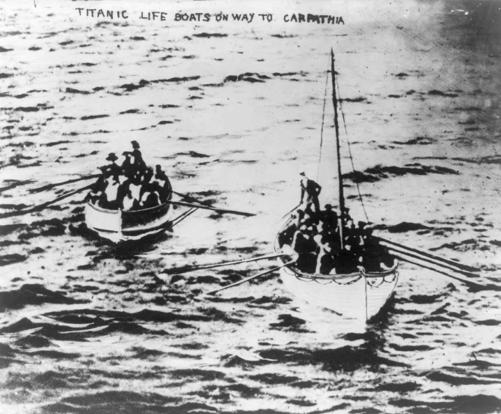

[Lifeboats making their way towards the

Carpathia

.]

LC-USZ 62-33430

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

[Survivors sit huddled on the decks of the

Carpathia

.]

LC-USZ 62-99341

Courtesy of the Library of Congress

An American Senate Inquiry into the sinking began straight away, while a British one followed in May and June. Many survivors, both crew and passengers, testified at these Inquiries, and public anger grew at the realisation that the huge loss of life could have been avoided. From then on, it was ordered that ocean-going liners must carry sufficient lifeboats for all passengers. Radio operators were to man their stations throughout the night and SOS became the recognised international distress call, while an international iceberg patrol was established.