Woman Hating (9 page)

Gynocide: Chinese Footbinding

The origins of Chinese footbinding, as of Chinese thought in general, belong to that amorphous entity called antiquity. The 10th century marks the beginning of the physical, intellectual, and spiritual dehumanization of women in China through the institution of footbinding. That institution itself, the implicit belief in its necessity and beauty, and the rigor with which it was practiced lasted another 10 centuries. There were sporadic attempts at emancipating the foot —some artists, intellectuals, and women in positions of power were the proverbial drop in the bucket. Those attempts, modest though they were, were doomed to failure footbinding was a political institution which reflected and perpetuated the sociological and psychological inferiority of women; footbinding cemented women to a certain sphere, with a certain function —women were sexual objects and breeders. Footbinding was mass attitude, mass culture —it was the key reality in a way of life lived by real women—10 centuries times that many millions of them.

It is generally thought that footbinding originated as an innovation among the dancers of the Imperial harem. Sometime between the 9th and 11th centuries, Emperor Li Yu ordered a favorite ballerina to achieve the “pointed look. ” The fairy tale reads like this:

Li Yu had a favored palace concubine named Lovely Maiden who was a slender-waisted beauty and a gifted dancer. He had a six-foot high lotus constructed for her out of gold; it was decorated lavishly with pearls and had a carmine lotus carpet in the center. Lovely Maiden was ordered to bind her feet with white silk cloth to make the tips look like the points of a moon sickle. She then danced in the center of the lotus, whirling about like a rising cloud.

1

From this original event, the bound foot received the euphemism “Golden Lotus, ” though it is clear that Lovely Maiden’s feet were bound loosely— she could still dance.

A later essayist, a true foot gourmand, described 58 varieties of the human lotus, each one graded on a 9-point scale. For example:

Type:

Lotus petal, New moon, Harmonious bow, Bamboo shoot, Water chestnut

Specifications:

plumpness, softness, fineness

Rank:

Divine Quality (A-1), perfectly plump, soft and fine

Wondrous Quality (A-2), weak and slender

Immortal Quality (A-3), straight-boned, independent

Precious Article (B-1), peacocklike, too wide, dis-proportioned

Pure Article (B-2), gooselike, too long and thin

Seductive Article (B-3), fleshy, short, wide, round (the disadvantage of this foot was that its owner could withstand a blowing wind)

Excessive Article (C-1), narrow but insufficiently pointed

Ordinary Article (C-2), plump and common

False Article (C-3), monkeylike large heel (could climb)

The distinctions only emphasize that footbinding was a rather hazardous operation. To break the bones involved or to modify the pressure of the bindings irregularly had embarrassing consequences — no girl could bear the ridicule involved in being called a “largefooted Demon” and the shame of being unable to marry.

Even the possessor of an A-1 Golden Lotus could not rest on her laurels —she had to observe scrupulously the taboo-ridden etiquette of bound femininity: (1) do not walk with toes pointed upwards; (2) do not stand with heels seemingly suspended in midair; (3) do not move skirt when sitting; (4) do not move feet when lying down. The same essayist concludes his treatise with this most sensible advice (directed to the gentlemen of course):

Do not remove the bindings to look at her bare feet, but be satisfied with its external appearance. Enjoy the outward impression, for if you remove the shoes and bindings the aesthetic feeling will be destroyed forever.

2

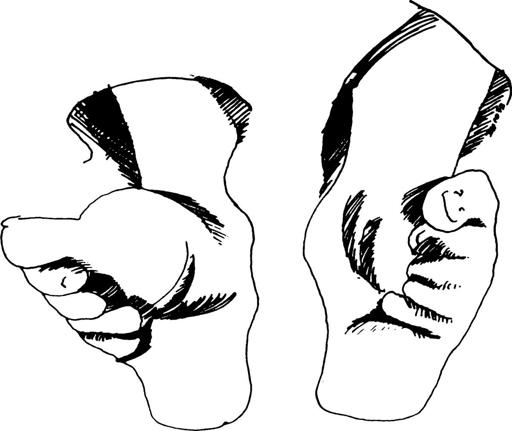

Indeed. The real feet looked like this:

(feet: 3 to 4 inches in length)

The physical process which created this foot is described by Howard S. Levy in

Chinese Footbinding: The History of a Curious Erotic Custom:

The success or failure of footbinding depended on skillful application of a bandage around each foot. The bandage, about two inches wide and ten feet long, was wrapped in the following way. One end was placed on the inside of the instep, and from there it was carried over the small toes so as to force the toes in and towards the sole. The large toe was left unbound. The bandage was then wrapped around the heel so forcefully that heel and toes were drawn closer together. The process was then repeated from the beginning until the entire bandage had been applied. The foot of the young child was subjected to a coercive and unremitting pressure, for the object was not merely to confine the foot but to make the toes bend under and into the sole and bring the heel and sole as close together as physically possible.

3

A Christian missionary observed:

The flesh often became putrescent during the binding and portions sloughed off from the sole; sometimes one or more toes dropped off.

4

An elderly Chinese woman, as late as 1934, remembered vividly her childhood experience:

Born into an old-fashioned family at P’ing-hsi, I was inflicted with the pain of footbinding when I was seven years old. I was an active child who liked to jump about, but from then on my free and optimistic nature vanished. Elder Sister endured the process from six to eight years of age [this means that it took Elder Sister two years to attain the 3-inch foot]. It was in the first lunar month of my seventh year that my ears were pierced and fitted with gold earrings. I was told that a girl had to suffer twice, through ear piercing and footbinding. Binding started in the second lunar month; mother consulted references in order to select an auspicious day for it. I wept and hid in a neighbor’s home, but Mother found me, scolded me, and dragged me home. She shut the bedroom door, boiled water, and from a box withdrew binding, shoes, knife, needle, and thread. I begged for a one-day postponement, but Mother refused: “Today is a lucky day, ” she said. “If bound today, your feet will never hurt; if bound tomorrow they will. ” She washed and placed alum on my feet and cut the toenails. She then bent my toes toward the plantar with a binding cloth ten feet long and two inches wide, doing the right foot first and then the left. She finished binding and ordered me to walk, but when I did the pain proved unbearable.

That night, Mother wouldn’t let me remove the shoes. My feet felt on fire and I couldn’t sleep; Mother struck me for crying. On the following days, I tried to hide but was forced to walk on my feet. Mother hit me on my hands and feet for resisting. Beatings and curses were my lot for covertly loosening the wrappings. The feet were washed and rebound after three or four days, with alum added. After several months, all toes but the big one were pressed against the inner surface. Whenever I ate fish or freshly killed meat, my feet would swell, and the pus would drip. Mother criticized me for placing pressure on the heel in walking, saying that my feet would never assume a pretty shape. Mother would remove the bindings and wipe the blood and pus which dripped from my feet. She told me that only with the removal of the flesh could my feet become slender. If I mistakenly punctured a sore, the blood gushed like a stream. My somewhat fleshy big toes were bound with small pieces of cloth and forced upwards, to assume a new moon shape.

Every two weeks, I changed to new shoes. Each new pair was one- to two-tenths of an inch smaller than the previous one. The shoes were unyielding, and it took pressure to get into them. Though I wanted to sit passively by the K’ang, Mother forced me to move around. After changing more than ten pairs of shoes, my feet were reduced to a little over four inches. I had been in binding for a month when my younger sister started; when no one was around, we would weep together. In summer, my feet smelled offensively because of pus and blood; in winter, my feet felt cold because of lack of circulation and hurt if they got too near the K'ang and were struck by warm air currents. Four of the toes were curled in like so many dead caterpillars; no outsider would ever have believed that they belonged to a human being. It took two years to achieve the three-inch model. My toenails pressed against the flesh like thin paper. The heavily-creased plantar couldn't be scratched when it itched or soothed when it ached. My shanks were thin, my feet became humped, ugly, and odiferous; how I envied the natural-footed!

5

Bound feet were crippled and excruciatingly painful. The woman was actually “walking” on the outside of toes which had been bent under into the sole of the foot. The heel and instep of the foot resembled the sole and heel of a high-heeled boot. Hard callouses formed; toenails grew into the skin; the feet were pus-filled and bloody; circulation was virtually stopped. The foot-bound woman hobbled along, leaning on a cane, against a wall, against a servant. To keep her balance she took very short steps. She was actually falling with every step and catching herself with the next. Walking required tremendous exertion.

Footbinding also distorted the natural lines of the female body. It caused the thighs and buttocks, which were always in a state of tension, to become somewhat swollen (which men called “voluptuous”). A curious belief developed among Chinese men that footbinding produced a most useful alteration of the vagina. A Chinese diplomat explained:

The smaller the woman’s foot, the more wondrous become the folds of the vagina. (There was the saying: the smaller the feet, the more intense the sex urge. ) Therefore marriages in Ta-t’ung (where binding is most effective) often take place earlier than elsewhere. Women in other districts can produce these folds artificially, but the only way is by footbinding, which concentrates development in this one place. There consequently develop layer after layer (of folds within the vagina); those who have personally experienced this (in sexual intercourse) feel a supernatural exaltation. So the system of footbinding was not really oppressive.

6

Medical authorities confirm that physiologically footbinding had no effect whatsoever on the vagina, although it did distort the direction of the pelvis. The belief in the wondrous folds of the vagina of footbound woman was pure mass delusion, a projection of lust onto the feet, buttocks, and vagina of the crippled female. Needless to say, the diplomat’s rationale for finding footbinding “not really oppressive” confused his “supernatural exaltation” with her misery and mutilation.

Bound feet, the same myth continues, “made the buttocks more sensual, [and] concentrated life-giving vapors on the upper part of the body, making the face more attractive. ”

7

If, due to a breakdown in the flow of these “life-giving vapors, ” an ugly woman was foot-bound and still ugly, she need not despair, for an A-1 Golden Lotus could compensate for a C-3 face and figure.

But to return to herstory, how did our Chinese ballerina become the millions of women stretched over 10 centuries? The transition from palace dancer to population at large can be seen as part of a class dynamic. The emperor sets the style, the nobility copies it, and the lower classes climbing ever upward do their best to emulate it. The upper class bound the feet of their ladies with the utmost severity. The Lady, unable to walk, remained properly invisible in her boudoir, an ornament, weak and small, a testimony to the wealth and privilege of the man who could afford to keep her— to keep her idle. Doing no manual labor, she did not need her feet either. Only on the rarest of occasions was she allowed outside of the incarcerating walls of her home, and then only in a sedan chair behind heavy curtains. The lower a woman’s class, the less could such idleness be supported: the larger the feet. The women who had to work for the economic survival of the family still had bound feet, but the bindings were looser, the feet bigger—after all, she had to be able to walk, even if slowly and with little balance.

Footbinding was a visible brand.

Footbinding did not emphasize the differences between men and women —it created them, and they were then perpetuated in the name of morality. Footbinding functioned as the Cerberus of morality and ensured female chastity in a nation of women who literally could not “run around. ” Fidelity, and the legitimacy of children, could be reckoned on.