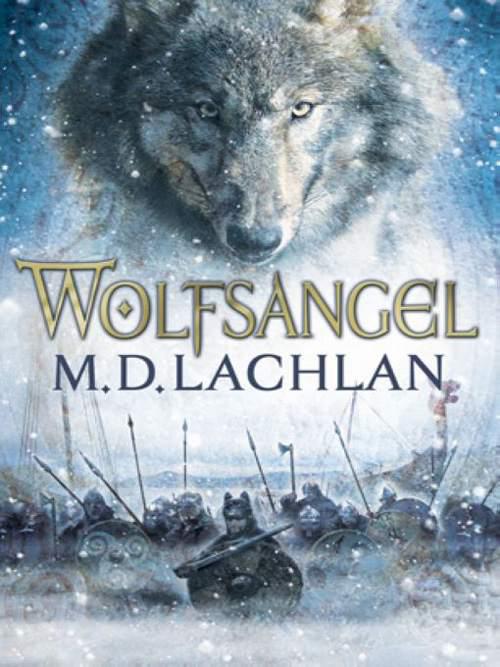

Wolfsangel

Authors: M. D. Lachlan

Table of Contents

Wolfsangel

M. D. LACHLAN

Orion

A Gollancz eBook

Copyright © M.D. Lachlan 2010

All rights reserved.

The right of M.D. Lachlan to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the

Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

First published in Great Britain in 2010 by Gollancz

The Orion Publishing Group Ltd

Orion House

5 Upper Saint Martin’s Lane

London, WC2H 9EA

An Hachette UK Company

This eBook first published in 2010 by Gollancz.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

eISBN : 978 0 5750 8962 4

This eBook produced by Jouve, France

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor to be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published without a similar condition, including this condition, being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

To my son James

Prince you cannot

talk about me

like that,

scolding a

noble man.

For you ate

a wolf’s treat,

shedding your brother’s

blood, often

you sucked on wounds

with a cold snout,

creeping to

dead bodies,

being hated by all.FIRST POEM OF HELGI HUNDINGSBANITHE POETIC EDDA

If only there were evil people somewhere insidiously committing evil deeds, and it were necessary only to separate them from the rest of us and destroy them. But the line dividing good and evil cuts through the heart of every human being - and who is willing to destroy a piece of his own heart?

ALEKSANDR SOLZHENITSYN

1 White Wolf

Varrin gripped the shaft of his spear and scanned the dark horizon, fighting for balance as the waves rocked the little longship. There, he was sure, was the river his lord had described, a broad mouth between two headlands, one like a dragon’s back, the other like a stretching dog. It fitted well enough, he thought, if you looked at it with half an eye.

‘Lord Authun, king, I think this is it.’

The man sitting in his cloak with his back to the prow awoke. His long white hair seemed almost to shine under the bright lantern of the half moon. He stood slowly, his limbs stiff with inaction and the cold. He turned his attention to the shore.

‘Yes,’ he said, ‘this is as was revealed.’

Varrin, a giant of a man a head and a half taller than the king, touched an amulet he wore at his neck at the mention of prophecy. ‘We wait until dawn and then try the river, lord?’

Authun shook his head.

‘Now,’ he said. ‘Odin is with us.’

Varrin nodded. Normally he would have regarded it as very unwise to negotiate an unknown river in the dark. With his king at his side, anything felt possible. Authun was a Volsung, a direct descendant of the gods and was a vessel for their powers.

The tide was slow but with the boat, and the crew were well rested from the favourable wind that had carried them for a couple of days and eager to get to the oars. Everything was going well, and no wonder with the king on board. His magic, Varrin felt sure, had blessed their journey.

The men bent their backs pulling through the waves, propelling themselves at speed towards the river. The ship was more stable under oar than under sail and its sudden steadiness seemed to reflect the purpose Varrin felt as he heaved the boat through the surf. They were going into a fight, no question, and Varrin was ready.

Ten warriors crewed the ship, only ten including the king, but Varrin felt no uncertainty, nor scarcely any nervousness. He was with his lord, King Authun, victor of innumerable battles, slayer of the giant Geat, Gyrd the Mighty. If Authun thought ten men were enough for their task then ten men were enough. It was a trick of the gods that such a man had not produced an heir. The rumour was that Authun was descended from Odin, the chief of the gods. That battle-fond poet felt threatened by his fierce descendant and had cursed Authun to sire only female children. He could not risk him producing an even mightier son.

Varrin shivered when he thought of the consequences if Authun did not father a boy. He would have to name an heir, with all the trouble and bloodshed that would cause. Only Authun’s name held the factions of his kingdom together. Without it, there would be slaughter and then their enemies would pounce. He glanced at the king and smiled to himself. He wouldn’t put it past him to live for ever.

Varrin looked into the black hills and wondered why they had come to that land. It was more than just plunder, it seemed, because their ship had slipped away from a quiet beach a day up the coast from their hall, no kinsmen to bid them farewell, no feasting before they left. Only the war gear, the bright heads of the axes, a shield decorated with a painted wolf’s head, another with a raven, spoke of their mission. The images bore a clear message to their enemies: ‘We will make a feast for these creatures.’

They rushed upon the river’s mouth but slowed as the water became more shallow. They did not stop for soundings; Authun just made his way to the prow of the ship and leaned out over the water, directing the rudderman. Varrin smirked to the man at the oar opposite as the ship slid into the river like a knife into a sheath. The other oarsman, a young man of seventeen or so who had never travelled with Authun before, grinned back. ‘You were right - he is incredible,’ his expression said. They were proud of their king.

The flood tide took them up the river. The channel became perilous and narrow, split into the land between sharp cliffs and hard boulders, but the king found the course. An hour inland with the dark tight about them, their only light a pale slice of moon high in the sky, the push of the current began to fade and the rowing got harder. In front of them a sandbank loomed midstream and Authun signalled for the boat to beach upon it. The small ship was designed for just such a landing and grounded with a slight judder.

Authun turned to his men and spoke their names in turn.

‘Vigi, Eyvind, Egil, Hella, Kol, Vott, Grani, Arngeir. We are kinsmen and sworn brothers. There can be no lies between us. None of you shall return from this journey. Only Varrin will come back with me to the coast to steer the ship. By the time the sun rises you will all be feasting with your forefathers in the halls of Odin or Freya.’

The men largely received the news of their impending deaths without expression. They were warriors, raised with the certainty of death in battle. A couple smiled, pleased that they would die at their king’s side.

‘I would die with my kinsmen,’ said Varrin.

‘Your time will come soon enough,’ said Authun.

He looked at Varrin, the nearest he had to a friend. The giant would be needed to get the boat back into the river and to help him with whatever perils they faced back down the whale road to their home. After that he would let him die.

‘I have no responsibility to tell you why you must die, other than it is my will that you should. But know that they will sing tales of your deeds until the world ends. We are here to take a magic child, one who will secure the future of our people for ever and one who will be my heir.’

‘What of the child your wife carries?’ said Varrin.

‘There is no child,’ said Authun. ‘It is a deception of the mountain witches.’

The men drew in breath. Authun was a good king, fair and generous, a giver of rings. He had never even killed a slave in drunkenness, as kings were wont to do. This was shocking news, though. The men despised liars and this was very near to a lie. Also, it bore the mark of magic, and women’s magic at that.

The warriors shifted in their seats. Death did not scare them; they found it as companionable as a dog. But the mountain witches terrified them. Only the king, half a god himself, could speak to the witches and even he had to be wary. Their advice had proved true in the past but the sacrifices they demanded were terrible and always the same - children: boys for servants, girls to continue their strange traditions.

‘The child is a captive in the village here, taken from the sorcerers of the far west,’ said Authun. ‘He is a son of the gods and will lead us to greatness. These farmers do not yet realise what they have. We will part them from it before they do. The village is defended only by farmers but there are warriors not two hours’ ride away.’

Other books

The Husband by John Simpson

The Graves of Saints by Christopher Golden

Beyond Band of Brothers by Major Dick Winters, Colonel Cole C. Kingseed

Sugar Dust by Raven ShadowHawk

My Fight / Your Fight by Ronda Rousey

The Shadow Realm (The Age of Dawn Book 4) by Everet Martins

Setting Him Free by Alexandra Marell

Master of Seduction by Kinley MacGregor

Living With Regret by Riann C. Miller