Wish You Were Here (22 page)

Some of the

Unplugged

audience enjoying themselves. Mark Wing-Davey and Richard Harris are visible in the foreground. Richard Creasey, Salman Rushdie and the author can be spotted towards the back.

Jill Furmanovsky

The directors of The Digital Village in Ed Victor’s office in the spring of 1996.

Standing (left to right):

Richard Harris, Mary Glanville, Ian Stewart, Richard Creasey, and Ed Victor.

Sitting:

Douglas and Robbie Stamp.

Jane Belson

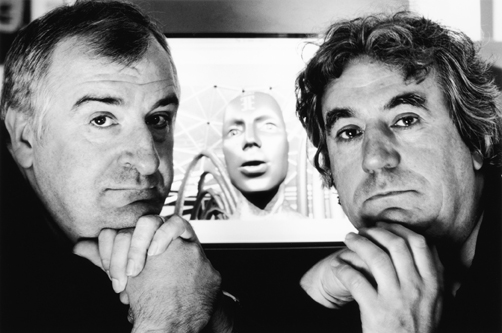

Terry Jones and Douglas in a promo picture for

Starship Titanic

in 1998.

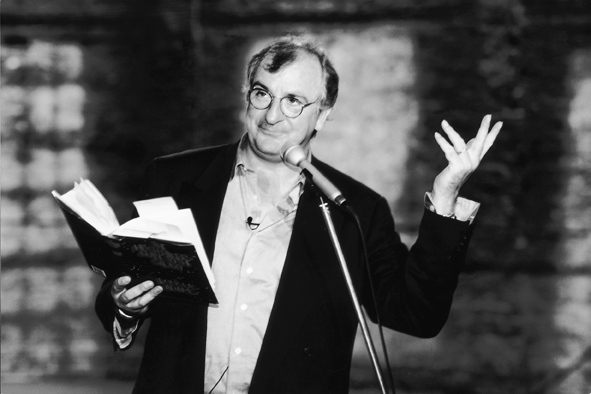

Douglas’s lectures and readings were theatrical performances. In typical thespian mode at the Almeida Theatre, Islington, in 1996.

Jane, Polly and Douglas lived here, their second and favorite house in Santa Barbara.

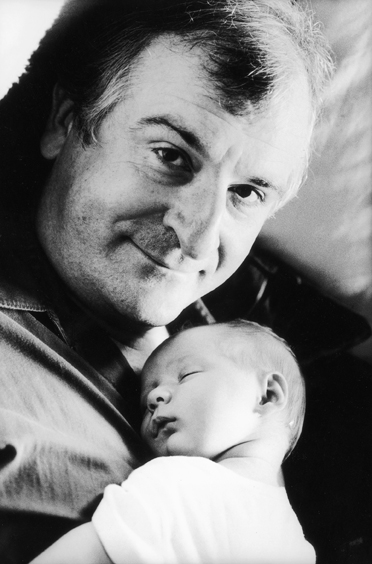

Polly and her proud father in July 1994.

SEVEN

Hearing the Music

“When I hear Mozart, I understand what it is to be a human being; when I hear Beethoven, I understand what it is to be Beethoven; but when I listen to Bach, I understand what it is to be the universe.”

D

OUGLAS

A

DAMS

, on

BBC’

s R

ADIO

F

OUR

,

Private Passions

H

amish Hamilton, the publisher, used to count Raymond Chandler among his friends and authors, two categories of humankind then more likely to overlap than in the current era of corporate media cartels. He once wrote to Chandler asking for a pre-publication quote for a book that Hamish Hamilton was about to publish. Publishers were pretty shameless, even in the era of urbane gentlemen who thought it bad form to poach each other’s authors.

Chandler wrote back a wonderful letter about life in California, the perils of alcohol and the state of his marriage. He didn’t ignore the plea for a quote. Instead he wrote something that has such profound relevance to publishing then as now that it should be carved on every editor’s desk in 72-point Arial Bold. This chap, he observed, can construct a perfectly grammatical and efficient sentence, but

he just doesn’t hear the music.

Douglas heard the music. Writers often worry that they are losing control of their prose, and are just letting it ramble on and on, with lots of proliferating subordinate clauses, like that one, which take on a momentum of their own, so by the time the readers have laboured to the end of a sentence, the main verb—a locomotive pulling a great train of carriages along the rails of grammar—has been quite forgotten. It’s the kind of prose that is all too easy to write, but painful to read. One of the traditional correctives for this nasty literary complaint is to read aloud what you’ve written. When a sentence can only be read in a single breath if you happen to be a skin-diver or an orchestral flautist, it’s too long.

Douglas Adams understood this deeply. He felt the rhythm of words, the lilt of a well-tuned phrase. His ear was acute, and this is something particularly important in comic writing when a clumsy word can drain the humour from a sentence. P.G. Wodehouse (to whom Douglas’s work often pays homage) had the same gift; he would polish and polish his prose, pinning his pages of text to the wall of his study and editing them vertically so that gradually the pages moved higher as they improved. Plum, as Wodehouse was known to his friends, only promoted his text to his eye-line when it was perfect. Unlike Douglas, however, he loved composition and regarded life as a regrettable series of interruptions to writing. With Douglas it was the other way around.*

116

Douglas’s style—funny, fluid, conversational and full of amusing tropes and inventive images—is clearly influenced by Plum. Is this Adams or Wodehouse, for instance?

He slid gracelessly off his seat and peered upwards to see if he could spot the owner of this discourteous hand. The owner was not hard to spot, on account of his being something of the order of seven feet tall and not slightly built with it. In fact he was built the way one builds leather sofas, shiny, lumpy and with lots of stuffing. The suit into which the man’s body had been stuffed looked as if its only purpose in life was to demonstrate how difficult it was to get this sort of body into a suit. The face had the texture of an orange and the colour of an apple, but there the resemblance to anything sweet ended.

This monster is Hotblack Desiato’s bodyguard in

The Restaurant at the End of the Universe

(Hotblack, you’ll recall, is taking a year off, dead, for tax reasons) but there’s an affectionate nod in the direction of Wodehouse’s description of the Reverend “Beefy” Bingham, the massive Oxford rower who so nearly lost the heart of Gertrude, Lord Emsworth’s niece, to the weedy but dangerous crooner, Orlo Watkins. Compare the rhythm of Douglas’s piece, for instance, with this account of Lord Emsworth being saved from drowning by “Beefy.”

If there was one thing the Rev. Rupert Bingham, who in his day had swum for Oxford, knew, it was what to do when drowning men struggled. Something that might have been a very hard and knobbly leg of mutton smote Lord Emsworth violently behind the ear: the sun was turned off at the main: the stars came out, many of them of a singular brightness: there was a sound of rushing waters: and he knew no more.*

117

Douglas described his rediscovery of Wodehouse in an article in the

Guardian.

*

118

I suddenly realized, with goose-pimples rising all over me, that I was in the presence of a great master.

Since then I have devoured his work repeatedly and voraciously, not merely because he is a great comic writer, but because he is arguably the greatest musician of the English language I have ever encountered. He may not have anything to say about Real Life (he would hoot at the very idea) but art practised at that level doesn’t have to be

about

anything.

Norman Mailer once said that Hemingway was a son of a bitch, but that as a writer he was one of those rare people who “can write sentences that are impossible to change.” It’s a good test. Take your favourite piece from one of Douglas’s novels and try to substitute your own words for the ones he used. Nothing else works so well. Mailer was spot on about Hemingway, but of the other “mainstream” writers, perhaps only Nabokov, at his most excruciatingly lapidary, placed words on the page with the same precision as Douglas or Plum at the height of their powers.

In many ways comedy is more difficult to write than “serious” literature. The word “serious” above is in inverted commas not because of any doubt about the quality of authors like A.S. Byatt and Iris Murdoch, with their fine observations of the velleities of human relations, but because it is possible to be serious

and

funny. Douglas’s books are witty about big questions (the existence of God, what it is that can be said to be real, man’s place in the universe . . .) but not so hot on the existential burdens of being an unhappy civil servant with a constipated love life. The reader can choose of course . . .

Douglas’s sensitivity to the rhythms of a sentence was intimately connected with his love of music. His ears were opened back at school where he sang in the choir and had piano lessons. He did not have many opportunities for escaping from Brentwood and going to concerts, but in 1969 he did hear Jacques Loussier and his Play Bach band doing their subtle jazzy versions of Bach, and he was completely won over.

Douglas was admirably strong-willed about mastering technique. He had a finger-picking guitar style and would practise relentlessly until he had something off accurately. Usually he chose tunes that appealed to his romantic and complex nature, lyrical tunes you could lose yourself in. Douglas was no three-chord wonder; he would study all the trickiest guitar parts—Paul Simon and McCartney were favourites—until he could play them fluently, twiddly bits and all. When he heard Procol Harum’s

A Whiter Shade of Pale

in 1967 he pestered all his relatives to buy him the album for Christmas, and set about learning many of the tracks.

Sue Adams remembers that, as an adult, he took his binoculars to a Dire Straits gig at the Birmingham NEC and spent much of the concert, indifferent to the odd looks from those nearby, peering closely at Mark Knopfler’s fingers. Then he had to mentally adjust what he saw to make it work for a left-handed guitar, which is strung so that the pitch of the strings is in the reverse order from a guitar tuned for a right-hander.

Interestingly, as a musician Douglas suffered from the same complaint that made all those clever Cambridge thespians reluctant to act with him on stage: for him ensemble playing was difficult. Ken Follett, the author, whose wife, Barbara, is the highly effective Labour MP for Stevenage, is famous for bestsellers like

The Eye of the Needle

and

The Pillars of the Earth.

He is less well known as a funky bass guitarist in the band Damn Right I Got the Blues. He jammed with Douglas a lot. Douglas’s agent, Ed Victor (a man whose address book must encompass most of the known media world), had suggested that they might enjoy playing together—and they did.

Ken is one of the most articulate human beings on Earth.*

119

He says:

I’m not a virtuoso—quite the reverse. The pleasure of music is sharing it with other people, usually guys. The buzz is making something collectively. So I like that, and I have—astonishing though it will be to my friends and family—not much of an ego when it comes to music. I’m happy to be the background guy playing the bass guitar. So when Douglas and I played together, I was really his accompanist. He was the virtuoso.

He could certainly play very complicated things on the guitar, and on his own he was fine, and with an accompanist who was willing to follow his tempo and his pace, he was fine. It was partly a matter of skill, and partly determination. He would spend time learning things. Wonderful, wonderful musicians like Paul McCartney and Paul Simon make them up, and if you want to copy them you have first to figure out what they are, and practise a lot. Douglas was willing to do that. He could play very nicely. And he could play with one other person, so he and I were quite good together. We enjoyed ourselves. We performed in Miami at an American Booksellers’ Association convention*

120

to some applause, and we performed in a club in London called L’Équipe Française, once again to considerable applause.

But he had one serious flaw which prevented him from being a really good musician, and that is no sense of time . . . When you perform with a real band with a drummer, you have to listen to the drummer. The drummer in a rock band is like the conductor of an orchestra who sets the pace and keeps it. You must listen to him and play on his beat. Douglas, bless his heart, was not able to do this. So when he did appear with us he would play a brilliant guitar solo, but would finish it half a beat before the rest of the band.

Before reading too much into the observation that Douglas was just a smidgen out of time with the rest of the world, this is a good moment for a brief anecdote about Paul Simon.

Douglas nearly had a close encounter with Paul Simon, a musician he admired without equivocation. When Douglas became famous and loaded, he spent a lot of time in New York. During one sojourn in Godless Gotham he decided that he would like to meet Paul Simon. Douglas could be quite no-nonsense about approaching celebrities, and, such was his own fame and his infectious enthusiasm, he usually ended up meeting them. In case you imagine this was a severe attack of status chasing, he was just as assiduous about tracking down the less famous as long as they fulfilled the one vital criterion—doing something interesting. His joy at other people’s achievements was engaging, and his generous admiration acted like a magnet.

Initially through Paul Simon’s record label, and then onwards via his management company, tentative contact was established. The rich and famous have “people,” as in “have your people call my people.” These people have hard eyes, careful haircuts, and easy smiles; they are paid to protect the privacy of their masters. Phone numbers are guarded by those whose jobs would not be worth a moment’s purchase if they divulged them to the wrong sort of reptile. Soundings are taken, bona fides are checked and the supplicant’s status and/or desirability are calculated, yea unto several decimal places. In short, getting access to the rich and famous is a gavotte with many tricky steps.

The vetting process was nearly complete. Douglas was adequately famous and clearly an abject fan of Paul Simon. A meeting was on the very point of being fixed when one of the aides asked, in a tone that did not appear to place that much freight on the question, “By the way, how tall are you?”

In all innocence Douglas replied—probably with an amusing riff on the subject (Mount Rushmore may have featured)—that he was very, very tall, quite ridiculously tall in fact. There followed what Hollywood calls a beat. Time stretched like chewing gum. “Umm,” said the aide finally, “I’m sorry, but your meeting with Paul will have to be postponed . . .” The encounter was never rearranged. It is possible, of course, that they had just missed the moment, or that Paul’s assistants were overly alert to the dangers of a photo opportunity. Paul Simon is five foot three.

Ed Victor, who is well over six feet tall and always elegantly turned out, commented on hearing this story that it was naïve of me to be surprised. “Nick,” he said, “surely you must have noticed along the way how much small men hate us. What’s going through their minds, which you can almost see like a subtitle on a French movie, is: why him, why not me?

Why him, why not me?

Why does he have the height? Why was he given this gift?”

Douglas’s mum says his interest in music started early. From the time he was a chorister at school, his love of choral music was life-long. Mercifully he never sang in public after his voice broke.

Paul Wickens, aka Wix, also went to Brentwood, though a couple of years behind Douglas. Although they were not particularly close as schoolboys, James Thrift reckons that the relationship gave Douglas access to a lot of contemporary music. There was a family connection too; Wix’s father, John Wickens, was the vet who looked after Grandma Donovan’s many animals so the links between the two families go back to the 1950s.

Wix and Douglas were reunited in a way that is characteristically Douglas. Wix’s partner, Margo Buchanan, the singer, describes it like this:

I met the Big One [an affectionate nickname for Douglas used by family and close friends] after a Paul McCartney gig. He actually went to the same school as Wix and they shared a music teacher. Douglas used to sometimes come round to Wix’s house and play with Wix’s older brother, David, when he was a boy. They do go back a long way, but I think there was a four-year age difference—something like that—between them. Anyway, Douglas went to a Paul McCartney gig one night—you know what he was like [about the Beatles]. He’d got hold of a ticket—he was someone’s guest, Robbie McIntosh’s I think. And he was reading the programme and had got to the part about Wix. And Wix actually mentioned his music teacher in the little blurb about him. So Douglas went, hang on a minute, that was my music teacher. That can’t be the same Wickens I used to go and play with as a child . . . I must find out . . .