Winter in Thrush Green (18 page)

Read Winter in Thrush Green Online

Authors: Miss Read

Dotty did not appear completely persuaded by this philosophy, but allowed Doctor Bailey to take her glass to be refilled, and then fluttered after him to change her mind. Ella remained alone on the sofa and all her old unhappiness suddenly flooded over her.

To all appearances this annual sherry party was like all the others. There was the blue and white bowl filled with Roman hyacinths and sprigs of red-berried holly. There was Winnie, as pink and white and gay as ever, wearing the deep blue suit that she had worn last year. And, she supposed, she herself presented the same tough leathery aspect that she always did.

But what a change had occurred in the last year! What a cataclysm had gone on in her heart! Nothing was the same, nothing was stable. Life had been turned topsy-turvy, and turmoil and conjecture tossed her to and fro. She looked again at the serene room, her old friends, and the placid indifferent countenance of Thrush Green through the window, and Ella

could have howled like a dog with abject misery at the hopelessness of ever trying to explain how different all her loved and little world was to her this Christmas Day.

At half-past one, in Albert Piggott's cottage, Molly was washing up the debris of the Christmas feast. Her father and Ben were accustomed to taking their main meal of the dav at twelve o'clock for they were early risers, and Molly too had risen soon after six after feeding her baby.

Ben wiped up vigorously, and his father-in-law leant in the doorway considerably impeding the progress. Occasionally Ben thrust a piece of crockery into his unwilling hands for him to put away in the cupboard. Conversation was carried on above the clatter at the sink and the cries of young George above who was impatiently awaiting his two o'clock feed. The child had been named after Ben's father, the favourite child of old Mrs Curdle, who had lost his life in the war. Doctor Bailey, to whom Molly had proudly shown her son that morning, maintained that he was the image of that baby he had delivered almost fifty years before.

'We'll leave you in peace this afternoon,' said Molly. 'Ted and Bessie Allen want to see the baby and we'll be there till they open the pub at six.'

'No need to hurry back on my account,' answered Albert sourly, squinting at a glass mug, in an unlovely way, to see if Ben had polished it sufficiently.

'Must be back by then,' said Molly firmly, 'to put George to bed. But if you want to go outâto see Nelly Tilling, sayâdon't wait about for us.'

It was pure mischief that had prompted Molly to speak of the widow, and Albert rose swiftly to the bait.

'Don't go getting ideas in your head about Nelly Tilling,' he growled. 'She be a rare one for chasing the men, as I've no

doubt you knows well enough. She ain't "ad no encouragement from me, that I can say.'

'More fool you,' said Ben cheerfully. 'You'd be lucky to get her. Look after you well, she would.'

'Too dam' well,' grunted Albert. 'Never let a chap forget c signed the pledge before his mother's milk 'ad dried on 'is lips.' He sniffed noisily. 'I "opes I've got more sense than to put me 'ead in that noose!'

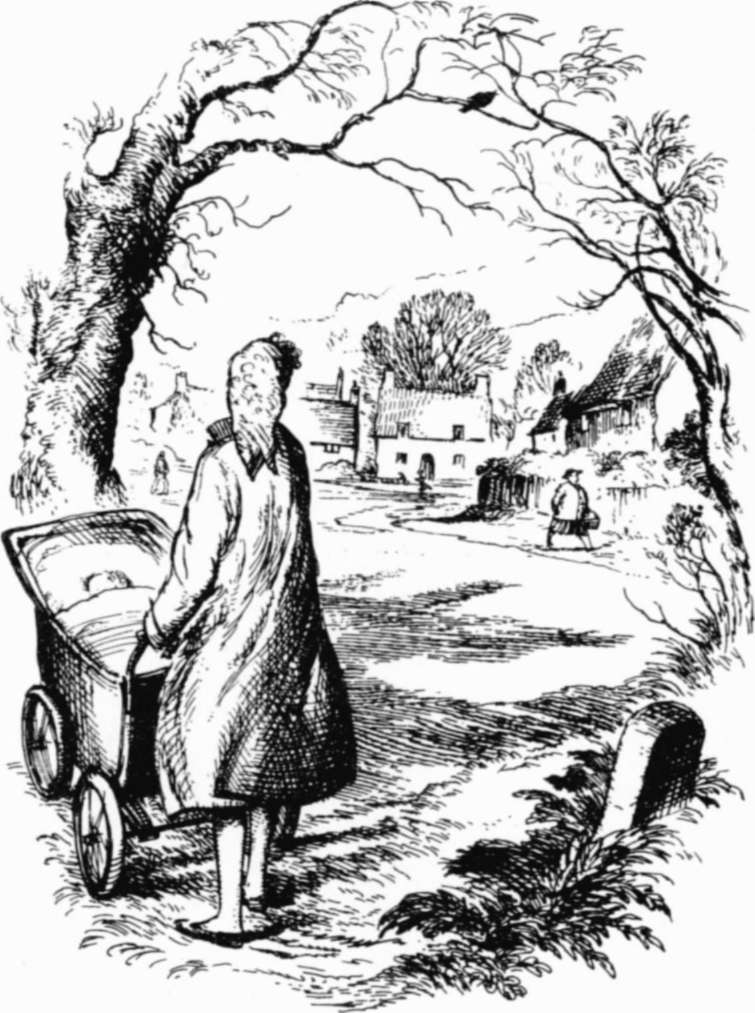

'Well, it seems to be expected,' said Molly lightly. 'Miss Watson asked me about her when I took the baby past her house this morning.'

'Miss Watson? That old faggot?' shouted Albert, shaken to his marrow. 'What call 'as she got to go linking Nelly Tilling and me?' He breathed heavily for a minute.

'She ain't never been right since she got hit on the head a month or two back,' he continued. 'Must've left her a bit dotty.'

'First I've heard of it,' said Ben. 'What happened?'

Albert gave a garbled account of the robbery at the school-house in the autumn.

'And the police,' he said, banging his hand on the dresser for emphasis, 'is fair scuppered. As a matter o' fact, I'm on the look-out for the chap meself.'

'Well, I hope you find him,' said Molly, undoing her apron. 'Poor old soul! Fancy hurting an old lady like Miss Watson! Why, she must be over fifty!'

Albert looked at himself in the kitchen mirror, and smirked.

'That ain't so old,' he said, with unusual jauntiness, brushing his damp mouth with the back of his hand. He caught the eye of his son-in-law and gave a watery wink.

Miss Watson, happily ignorant of the furore she had caused, was sitting snugly in the schoolhouse parlour,

spending her Christmas afternoon in writing letters of thanks.

She was engaged in giving a long account of the morning's service at St Andrew's to Miss Fogerty whose Christmas holiday was being spent with an octogenarian aunt at Tunbridge Wells.

'The church,' wrote Miss Watson in her precise copperplate, 'looked lovely, decorated with holly, red and white carnations and Christmas roses on the altar. You would have enjoyed the singing, and the rector's sermon was very fine, on the theme of generosity. Very much to the point, I thought, in a community like Thrush Green, where back-biting does occur, as we know only too well. It made me feel that I really must try and

forgive,

even if I cannot

forget,

that wretched man who attacked me.'

Miss Watson put down her pen for a moment and gazed thoughtfully out upon Thrush Green. The room was tranquil, and she was enjoying her holiday solitude. Now that she had time to collect her thoughts Miss Watson had gone carefully over and over the incidents of that terrifying night, but further clues escaped her. From the first she had felt that her attacker was someone that she knew. In the weeks that followed she scrutinised the men of Lulling and Thrush Green to no avail. But she had not, and would not, give up hope. One day, she felt certain, she would recognise the brute and he would be brought to justice.

The winter sun was beginning to turn to a red ball, low on the horizon. Above it, long grey clouds, like feathered arrows, strained across the clear ice-blue sky. Somewhere a blackbird sang, as though it were a spring day, and Miss Watson, suddenly finding the room stuffy, opened her window the better to hear it.

A family passed near by, crossing the green, no doubt bent upon taking tea with relatives. That indefinable Christmas afternoon atmosphere, compounded of cigar smoke, best clothes and new possessions crept upon Miss Watson's senses,

as she watched the father bending down to guide the erratic course of his young son's new red tricycle. Screaming with annoyance, the child beat backwards at his father's restraining hand. The mother's protests, shrill and tired, floated across the grass to the open window.

'There are times,' said Miss Watson smugly to the cat, 'when an old maid has the best of it.' And she turned, with a happy sigh, to her interrupted letterwriting.

While Miss Watson finished her letter and her neighbours slept or walked off the effects of their Christmas feasting, Ruth Lovell looked, for the first time, upon her daughter.

She weighed seven pounds and two ounces, had a tiny bright pink face mottled like brawn, and from each tightly-shut eye there protruded four short light eyelashes. But to Ruth, to whom good looks meant a great deal, the most alarming thing was the shape of her daughter's head, which rose to a completely bald pointed dome.

'Will she always look like this?' asked Ruth weakly of Tony Harding, who was busy packing his bag neatly. She did not like to seem ungrateful for his ministrations, but she was beginning to wonder, in the daze that surrounded her, whether he had not helped her give birth to a monster.

'Heavens, no!' was the brisk reply. 'That head will have gone down in a day or two. Believe me, you're going to have a very pretty little girl.'

Ruth smiled with relief and settled the baby more comfortably in her arms.

'It was too bad of me to bring you out on Christmas Day,' she said apologetically. 'I'm terribly sorry.'

'Think nothing of it,' replied the doctor, straightening up. 'All in the day's work.'

He made for the door.

'There's a very good precedent, you know,' he said cheerfully, and vanished.

The red sun had dropped behind the folds of the Cotswolds, and the short winter day was done by the time Albert Piggott shuffled across to St Andrew's to ring the bell for evensong.

Two or three bicycles were already propped against the railings, and a figure moved hastily away from them as Albert approached.

'Who's that? asked Albert, switching on a failing torch. By its pallid light he recognised Sam Curdle.

'Bike fell over. Just proppin' it up,' volunteered Sam, a shade too glibly. Albert looked at him with dislike and suspicion. He wouldn't mind betting Sam had been looking in the baskets and the saddlebags for any pickings, but as far as he could see the fellow held nothing in his hands. Albert grunted disbelievingly.

'Got yer cousin staying at my place,' he said at last. Sam did not appear delighted.

'Don't mean nothing to me,' he said spitefully. 'Ben and me never had no time for each other. He can go to the devil for all I care.'

'Well, that's your business,' said Albert, shuffling on again. I'll say good night to you.'

'Good night,' replied Sam shortly, and set off in the direction of Nidden. Albert, pausing on the church path, looked after his disappearing figure. A growing conviction shook his bent frame with excitement.

'If that fellow didn't do poor old Miss Watson,' thought Albert to himself, 'I'll eat my hat!'

And taking that greasy object from his bald head, he entered the church and made his way towards the belfry and his duty, highly elated.

The New Year

O

N

New Year's Day the rector and Harold Shoosmith set out on a long journey.

Four letters and a telegram, with a prepaid answer, had all faded to elicit any reply from Nathaniel Patten's grandson. His address had been found with the help of many people, and it appeared that William Mulloy lived in a remote hamlet in Pembrokeshire.

'The only thing to do,' Harold said, 'is to call on the fellow and try to get some answer from him. We'll stay the night somewhere. It's a longish drive and we may as well do it comfortably.'

After a few demurrings on the part of the conscientious rector, who had various meetings to rearrange in order to leave his parish for two days, the two men had decided that the first day of the New Year, which fell on a Friday, would suit them both admirably.

It had turned much colder. An easterly wind whipped the last few leaves from the hedges, and dried the puddles which had lain so long about Thrush Green. People went about their outdoor affairs with their coat collars turned up and their heads muffled in warm scarves. Gardeners found that digging in the cruel wind touched up forgotten rheumatism, and children began to complain of ear-ache. In Lulling the chemist displayed a choice selection of cough mixtures and throat lozenges. Winter, it seemed, was beginning in earnest.

The two men breakfasted very early, Harold Shoosrmth in his warm kitchen on eggs and bacon, and the rector walking about his bleak house with a piece of bread and marmalade in his hand, as he did his simple packing. It had seemed selfish to expect his housekeeper to rise so early, and she had not suggested it. She wished him a pleasant journey before retiring for the mght and said she would take the opportunity of washing the chair covers in his absence. With this small crumb of comfort the rector had to be content.

He felt rising excitement as he crossed Thrush Green from his gaunt vicarage to the corner house. The Reverend Charles Henstock had few pleasures, and an outing to Wales, albeit in January and in the teeth of a fierce easterly wind, was something to relish. It was still fairly dark, only a slight lightening of the sky in the east giving a hint of the coming dawn. One or two of the houses around the green showed a lighted window as early risers stumbled sleepily about their establishments.

The dignified old Daimler waited in the road outside Harold's gate. Its owner was busy wrapping chains in a piece of dingy blanket, and stowing them in the boot.

'Just in case we meet icy roads,' said Harold, in answer to the rector's query, and Charles Henstock marvelled at such wise foresight.

The car was warm and comfortable. After talking for the first few miles the two settled down into companionable silence, and the rector found himself nodding into a doze. He was happy and relaxed, pleased to be with such a good friend, and relieved to leave Thrush Green and its cares behind him for two days. He slumbered peacefully as the car rolled steadily westward.

Harold Shoosmith was glad to see him at rest. Nothing had come of the protest at the Fur and Feather Whist Drive, and it had been generally decided to press on with the arrangements for the memorial. But the rector had worried about it considerably, Harold Shoosmith knew. To his mind, the rector had a pretty thin time of it, and if he himself had ever been saddled with the sort of housekeeper Charles endured he would have sent her packing in double-quick time, he told himself. There were some men who were born to be married, and who were but half-men without the comfort of married estate. The good rector, he realised, was one of them, and he fell to speculating about a possible match for his unconscious friend. It would seem, as he reviewed the charms of the unattached ladies of distant Thrush Green, that the rector's chances were slight, thought Harold unchivalrously.