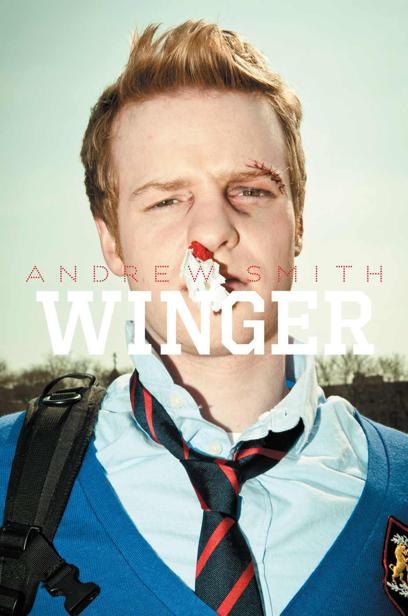

Winger

Authors: Andrew Smith

This is for my son, Trevin Smith,

who played rugby for me.

Until I broke his collarbone.

Now he writes.

TO PLAY RUGBY AND TO

be a rugby player are inextricably enmeshed. There is something about the sport that attaches to character. Some of the greatest people I will ever know are ruggers. This book would never have worked its way out of me and onto the page without them. Davis Russ, a fly half, and Kyle Alvarez, a lock, had the bravest and most honorable makeup of anyone I’ve ever known, on and off the pitch. They were the models for all the good, selfless things the kids in

Winger

do. Landon Drake Alexsander Veis, a center, and Beau Mitchell Donohoe, a scrum half, made me laugh so many times, and I apologize if any of the funny things in

Winger

are an embarrassment to them. My friend and fellow author Joe Lunievicz, a fullback, was the first “real” person who got to read this manuscript. He is, after all, a rugger, and I had to be certain that I did the sport justice. And to Amy—the author A. S. King—thanks for keeping me from going as crazy as I likely would have gone.

And what a great team

Winger

has. Many thanks to my editor, David Gale, and Navah Wolfe, for their faith and persistence in making this story come to life; and to Sam Bosma for his amazing and spot-on artwork.

I have endless appreciation and love for my wife and kids who put up with me. Writing is every bit as hard on them as it is on me, and it’s just as tough as rugby.

crede quod habes, et habes

I SAID A SILENT PRAYER.

Actually,

silent

is probably the only type of prayer a guy should attempt when his head’s in a toilet.

And, in my prayer, I made sure to include specific thanks for the fact that the school year hadn’t started yet, so the porcelain was impeccably white—as soothing to the eye as freshly fallen snow—and the water smelled like lemons and a heated swimming pool in summertime, all rolled into one.

Except it was a fucking toilet.

And my head was in it.

My feet, elevated in Nick Matthews’s apelike paws while Casey Palmer tried to drive my face down past the surface of the pleasant-smelling water, were somewhere between my skinny ass and Saturn, pointing toward the plane my parents were currently heading back to Boston in, and whatever else is up there.

I hate football players.

And I gave thanks, too, or I thought about it while grunting and grimacing, for the weights I’d lifted over the summer, because even though they were about to snap like pencils, my locked elbows kept my actual face about three inches away from actual toilet fucking water.

But then I felt bad, because I was convinced that cussing during a prayer—even a silent one—meant that I would make my rookie debut in hell as soon as Casey and Nick succeeded at drowning me in a goddamned school-issue community toilet.

And I realized that all those movies and stories about how clearly a guy’s thoughts and perceptions materialize in the expanding moments just before death were actually true, because I couldn’t help but notice the nearly transparent and unperforated one-ply toilet paper that curled downward from the shiny chrome toilet-paper-cover-thing-that-looks-like-an-eighteen-wheeler’s-mudflap-but-I-don’t-know-what-the-hell-those-devices-are-called, and I thought to myself,

God! They make us use THAT kind of toilet paper here?

And all this happened in the span of maybe three seconds, now that I think about it.

Oh, yeah. And I had spent the previous five weeks or so chanting a near-constant antiwimp, inner tantric mantra as an attempt to convince my brain that I was going to reinvent myself this year, that I wasn’t going to be the little kid everyone ignored or, worse, paid attention to for the purpose of constructing cruel survival experiments involving toilets and the tensile strength of my skinny-bitch arms.

My mom and dad—Dad especially—were always getting on me about paying better attention to stuff. It kind of choked me up to think how proud he’d be of his boy at that moment for all the minute details I was taking in about my new, upside-down toilet world.

But I guess I should have paid more attention earlier to the fact that room two, which was my dorm room, wasn’t the second fucking door down from the stairwell.

So when I walked in on Casey and Nick’s room—room six, whose location made absolutely no mathematical sense to me at all—carrying my suitcase and duffel bag, and they were somewhere near what I could only guess were the completion stages of rolling a joint (some kids, especially kids like Casey and Nick, do that here because the woods are like one big, giant pot party to them), they not only warned me, in a very creepy Greek-chorus-in-a-tragedy-that-you-know-is-not-going-to-end-well-for-our-hero kind of way, to not ever step foot in their fucking room again, they came up with this spontaneous welcoming ritual that involved a toilet, the elevation of my feet (one of which had detached itself from a shoe, the same way a lizard loses its tail to distract potential predators) . . . and me.

That was a really long sentence, wasn’t it?

I should probably stick to drawing pictures, which I do sometimes.

Okay. So there I was, in Upside-Down Toilet Land, about to collapse, wondering how bad toilet water could possibly taste, and I gritted my teeth and recited the convince-yourself mantra I’d been using:

“Crede quod habes, et habes,”

which means something like, if you believe in what you have, you’ll have it.

At that moment, I believed I’d have the ability to hold my breath for a really long time.

Grunt.

Big inhale.

And maybe some cosmic forces happened to perfectly converge in the Universe of the Upside-Down Toilet. Maybe O-Hall had some kind of spell on it; or maybe things really

were

going to be different for me this year, because just at the precise limit of my endurance, a voice called out from the hallway.

“Mr. Palmer! Mr. Matthews!”

And they let me go.

Feet and head reoriented themselves.

The universe, which smelled pretty nice and lemony, was right again.

Nick Matthews started giggling like an idiot. Come to think of it, he did just about everything that way.

And Casey said, “Fuck. It’s Farrow.”

The boys ran out of the bathroom and left me there, alone, kind of like the last clueless guy at a party who just doesn’t know when to go home.

But I wasn’t going home.

I had stuff to do.

the overlap of everyone

prologue

JOEY TOLD ME NOTHING EVER

goes back exactly the way it was, that things expand and contract—like breathing, but you could never fill your lungs up with the same air twice. He said some of the smartest things I ever heard, and he’s the only one of my friends who really tried to keep me on track too.

And I’ll be honest. I know exactly how hard that was.

NOTHING COULD POSSIBLY SUCK WORSE

than being a junior in high school, alone at the top of your class, and fourteen years old all at the same time. So the only way I braced up for those agonizing first weeks of the semester, and made myself feel any better about my situation, was by telling myself that it had to be better than being a senior at fifteen.

Didn’t it?

My name is Ryan Dean West.

Ryan Dean is my first name.

You don’t usually think a single name can have a space and two capitals in it, but mine does. Not a dash, a space. And I don’t really like talking about my middle name.

I also never cuss, except in writing, and occasionally during silent prayer, so excuse me up front, because I can already tell I’m going to use the entire dictionary of cusswords when I tell the story of what happened to me and my friends during my eleventh-grade year at Pine Mountain.

PM is a

rich kids’

school. But it’s not only a prestigious rich kids’ school; it’s also for rich kids who get in too much trouble because they’re alone and ignored while their parents are off being congressmen or investment bankers or professional athletes. And I know I wasn’t actually out of control, but somehow Pine Mountain decided

to move me into Opportunity Hall, the dorm where they stuck the really bad kids, after they caught me hacking a cell phone account so I could make undetected, untraceable free calls.

They nearly kicked me out for that, but my grades saved me.

I like school, anyway, which increases the loser quotient above and beyond what most other kids would calculate, simply based on the whole two-years-younger-than-my-classmates thing.

The phone was a teacher’s. I stole it, and my parents freaked out, but only for about fifteen minutes. That was all they had time for. But even in that short amount of time, I did count the phrase “You know better than that, Ryan Dean” forty-seven times.

To be honest, I’m just estimating, because I didn’t think to count until about halfway through the lecture.

We’re not allowed to have cell phones here, or iPods, or anything else that might distract us from “our program.” And most of the kids at PM completely buy in to the discipline, but then again, most of them get to go home to those things every weekend. Like junkies who save their fixes for when there’s no cops around.

I can understand why things are so strict here, because it is the best school around for the rich deviants of tomorrow. As far as the phone thing went, I just wanted to call Annie, who was home for the weekend. I was lonely, and it was her birthday.

I already knew that my O-Hall roommate was going to be Chas Becker, a senior who played second row on the school’s rugby team.

Chas was as big as a tree, and every bit as smart, too. I hated him, and it had nothing to do with the age-old, traditional rivalry between backs and forwards in rugby. Chas was a friendless jerk who navigated the seas of high school with his rudder fixed on a steady course of intimidation and cruelty. And even though I’d grown about four inches since the end of last year and liked to tell myself that I finally—

finally!

—didn’t look like a prepubescent minnow stuck in a pond of hammerheads like Chas, I knew that my reformative dorm assignment with Chas Becker in the role of bunk-bed mate was probably nothing more than an “opportunity” to go home in a plastic bag.

But I knew Chas from the team, even though I never talked to him at practice.

I might have been smaller and younger than the other boys, but I was the fastest runner in the whole school for anything up to a hundred meters, so by the end of the season last year, as a thirteen-year-old sophomore, I was playing wing for the varsity first fifteen (that’s first string in rugby talk).