William Shakespeare: The Complete Works 2nd Edition (98 page)

Read William Shakespeare: The Complete Works 2nd Edition Online

Authors: William Shakespeare

Tags: #Drama, #Literary Criticism, #Shakespeare

BOOK: William Shakespeare: The Complete Works 2nd Edition

4.08Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

⌈TITUS⌉

Treason, my lord! Lavinia is surprised.

SATURNINUS

Surprised, by whom?

BASSIANUS

By him that justly may

Bear his betrothed from all the world away.

C. AFTER 4.3.93

The following lines, found in the early texts, appear to be a draft of the subsequent six lines.

MARCUS (to Titus) Why, sir, that is as fit as can be to serve for your oration, and let him deliver the pigeons to the Emperor from you.

TITUS (to the Clown) Tell me, can you deliver an oration to the Emperor with a grace?

CLOWN Nay, truly, sir, I could never say grace in all my life.

RICHARD III

IN narrative sequence,

Richard III

follows directly after

Richard Duke of York

, and that play’s closing scenes, in which Richard of Gloucester expresses his ambitions for the crown, suggest that Shakespeare had a sequel in mind. But he seems to have gone back to tell the beginning of the story of Henry VI’s reign before covering the events from Henry VI’s death (in 1471) to the Battle of Bosworth (1485). We have no record of the first performance of

Richard III

(probably in late 1592 or early 1593, outside London); it was printed in 1597, with five reprints before its inclusion in the 1623 Folio.

Richard III

follows directly after

Richard Duke of York

, and that play’s closing scenes, in which Richard of Gloucester expresses his ambitions for the crown, suggest that Shakespeare had a sequel in mind. But he seems to have gone back to tell the beginning of the story of Henry VI’s reign before covering the events from Henry VI’s death (in 1471) to the Battle of Bosworth (1485). We have no record of the first performance of

Richard III

(probably in late 1592 or early 1593, outside London); it was printed in 1597, with five reprints before its inclusion in the 1623 Folio.

The principal source of information about Richard III available to Shakespeare was Sir Thomas More’s

History of King Richard III

as incorporated in chronicle histories by Edward Hall (1542) and Raphael Holinshed (1577, revised in 1587), both of which Shakespeare seems to have used. His artistic influences include the tragedies of the Roman dramatist Seneca (who was born about 4 BC and died in AD 65), with their ghosts, their rhetorical style, their prominent choruses, and their indirect, highly formal presentation of violent events. (Except for the stabbing of Clarence (1.4) there is no on-stage violence in

Richard III

until the final battle scenes.)

History of King Richard III

as incorporated in chronicle histories by Edward Hall (1542) and Raphael Holinshed (1577, revised in 1587), both of which Shakespeare seems to have used. His artistic influences include the tragedies of the Roman dramatist Seneca (who was born about 4 BC and died in AD 65), with their ghosts, their rhetorical style, their prominent choruses, and their indirect, highly formal presentation of violent events. (Except for the stabbing of Clarence (1.4) there is no on-stage violence in

Richard III

until the final battle scenes.)

In this play, Shakespeare demonstrates a more complete artistic control of his historical material than in its predecessors: Richard himself is a more dominating central figure than is to be found in any of the earlier plays, historical events are freely manipulated in the interests of an overriding design, and the play’s language is more highly patterned and rhetorically unified. That part of the play which shows Richard’s bloody progress to the throne is based on the events of some twelve years; the remainder covers the two years of his reign. Shakespeare omits some important events, but invents Richard’s wooing of Lady Anne over her father-in-law’s coffin, and causes Queen Margaret, who had returned to France in 1476 and who died before Richard became king, to remain in England as a choric figure of grief and retribution. The characterization of Richard as a self-delighting ironist builds upon More. The episodes in which the older women of the play—the Duchess of York, Queen Elizabeth, and Queen Margaret—bemoan their losses, and the climactic procession of ghosts before the final confrontation of Richard with the idealized figure of Richmond, the future Henry VII, help to make

Richard III

the culmination of a tetralogy as well as a masterly poetic drama in its own right. The final speech, in which Richmond, heir to the house of Lancaster and grandfather of Queen Elizabeth I, proclaims the union of ‘the white rose and the red’ in his marriage to Elizabeth of York, provides a patriotic climax which must have been immensely stirring to the play’s early audiences.

Richard III

the culmination of a tetralogy as well as a masterly poetic drama in its own right. The final speech, in which Richmond, heir to the house of Lancaster and grandfather of Queen Elizabeth I, proclaims the union of ‘the white rose and the red’ in his marriage to Elizabeth of York, provides a patriotic climax which must have been immensely stirring to the play’s early audiences.

Colley Cibber’s adaptation (1700) of

Richard III,

incorporating the death of Henry VI, shortening and adapting the play, and making the central role (played by Cibber) even more dominant than it had originally been, held the stage with great success until the late nineteenth century. Since then, Shakespeare’s text has been restored (though usually abbreviated—next to

Hamlet

, this is Shakespeare’s longest play), and the role of Richard has continued to present a rewarding challenge to leading actors.

Richard III,

incorporating the death of Henry VI, shortening and adapting the play, and making the central role (played by Cibber) even more dominant than it had originally been, held the stage with great success until the late nineteenth century. Since then, Shakespeare’s text has been restored (though usually abbreviated—next to

Hamlet

, this is Shakespeare’s longest play), and the role of Richard has continued to present a rewarding challenge to leading actors.

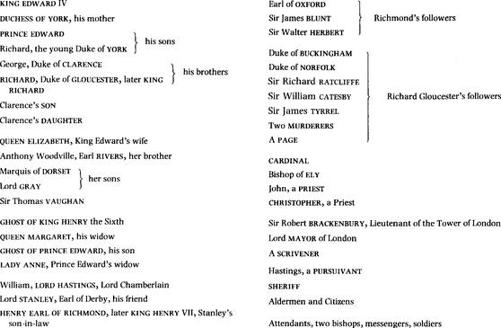

THE PERSONS OF THE PLAY

Enter Richard Duke of Gloucester

RICHARD GLOUCESTER

Now is the winter of our discontent

Made glorious summer by this son of York;

And all the clouds that loured upon our house

In the deep bosom of the ocean buried.

Now are our brows bound with victorious wreaths,

Our bruised arms hung up for monuments,

Our stern alarums changed to merry meetings,

Our dreadful marches to delightful measures.

Grim-visaged war hath smoothed his wrinkled front,

And now—instead of mounting barbed steeds

To fright the souls of fearful adversaries—

He capers nimbly in a lady’s chamber

To the lascivious pleasing of a lute.

Made glorious summer by this son of York;

And all the clouds that loured upon our house

In the deep bosom of the ocean buried.

Now are our brows bound with victorious wreaths,

Our bruised arms hung up for monuments,

Our stern alarums changed to merry meetings,

Our dreadful marches to delightful measures.

Grim-visaged war hath smoothed his wrinkled front,

And now—instead of mounting barbed steeds

To fright the souls of fearful adversaries—

He capers nimbly in a lady’s chamber

To the lascivious pleasing of a lute.

But I, that am not shaped for sportive tricks

Nor made to court an amorous looking-glass,

I that am rudely stamped and want love’s majesty

To strut before a wanton ambling nymph,

I that am curtailed of this fair proportion,

Cheated of feature by dissembling nature,

Deformed, unfinished, sent before my time

Into this breathing world scarce half made up—

And that so lamely and unfashionable

That dogs bark at me as I halt by them—

Why, I in this weak piping time of peace

Have no delight to pass away the time,

Unless to spy my shadow in the sun

And descant on mine own deformity.

Nor made to court an amorous looking-glass,

I that am rudely stamped and want love’s majesty

To strut before a wanton ambling nymph,

I that am curtailed of this fair proportion,

Cheated of feature by dissembling nature,

Deformed, unfinished, sent before my time

Into this breathing world scarce half made up—

And that so lamely and unfashionable

That dogs bark at me as I halt by them—

Why, I in this weak piping time of peace

Have no delight to pass away the time,

Unless to spy my shadow in the sun

And descant on mine own deformity.

And therefore since I cannot prove a lover

To entertain these fair well-spoken days,

I am determined to prove a villain

And hate the idle pleasures of these days.

Plots have I laid, inductions dangerous,

By drunken prophecies, libels and dreams

To set my brother Clarence and the King

In deadly hate the one against the other.

And if King Edward be as true and just

As I am subtle false and treacherous,

This day should Clarence closely be mewed up

About a prophecy which says that ‘G’

Of Edward’s heirs the murderer shall be.

To entertain these fair well-spoken days,

I am determined to prove a villain

And hate the idle pleasures of these days.

Plots have I laid, inductions dangerous,

By drunken prophecies, libels and dreams

To set my brother Clarence and the King

In deadly hate the one against the other.

And if King Edward be as true and just

As I am subtle false and treacherous,

This day should Clarence closely be mewed up

About a prophecy which says that ‘G’

Of Edward’s heirs the murderer shall be.

Enter George Duke of Clarence, guarded, and Sir Robert Brackenbury

Dive, thoughts, down to my soul: here Clarence comes.

Brother, good day. What means this armèd guard

That waits upon your grace?

Brother, good day. What means this armèd guard

That waits upon your grace?

CLARENCE

His majesty,

Tend’ring my person’s safety, hath appointed

This conduct to convey me to the Tower.

This conduct to convey me to the Tower.

RICHARD GLOUCESTER

Upon what cause?

CLARENCE

Because my name is George.

RICHARD GLOUCESTER

Alack, my lord, that fault is none of yours.

He should for that commit your godfathers.

Belike his majesty hath some intent

That you should be new-christened in the Tower.

But what’s the matter, Clarence? May I know?

He should for that commit your godfathers.

Belike his majesty hath some intent

That you should be new-christened in the Tower.

But what’s the matter, Clarence? May I know?

CLARENCE

Yea, Richard, when I know—for I protest

As yet I do not. But as I can learn

He hearkens after prophecies and dreams,

And from the cross-row plucks the letter ‘G’

And says a wizard told him that by ‘G’

His issue disinherited should be.

And for my name of George begins with ‘G’,

It follows in his thought that I am he.

These, as I learn, and suchlike toys as these,

Hath moved his highness to commit me now.

As yet I do not. But as I can learn

He hearkens after prophecies and dreams,

And from the cross-row plucks the letter ‘G’

And says a wizard told him that by ‘G’

His issue disinherited should be.

And for my name of George begins with ‘G’,

It follows in his thought that I am he.

These, as I learn, and suchlike toys as these,

Hath moved his highness to commit me now.

RICHARD GLOUCESTER

Why, this it is when men are ruled by women.

‘Tis not the King that sends you to the Tower;

My Lady Gray, his wife—Clarence, ’tis she

That tempts him to this harsh extremity.

Was it not she, and that good man of worship

Anthony Woodeville her brother there,

That made him send Lord Hastings to the Tower,

From whence this present day he is delivered?

We are not safe, Clarence; we are not safe.

‘Tis not the King that sends you to the Tower;

My Lady Gray, his wife—Clarence, ’tis she

That tempts him to this harsh extremity.

Was it not she, and that good man of worship

Anthony Woodeville her brother there,

That made him send Lord Hastings to the Tower,

From whence this present day he is delivered?

We are not safe, Clarence; we are not safe.

CLARENCE

By heaven, I think there is no man secure

But the Queen’s kindred, and night-walking heralds

That trudge betwixt the King and Mrs Shore.

Heard ye not what an humble suppliant

Lord Hastings was for his delivery?

But the Queen’s kindred, and night-walking heralds

That trudge betwixt the King and Mrs Shore.

Heard ye not what an humble suppliant

Lord Hastings was for his delivery?

RICHARD GLOUCESTER

Humbly complaining to her deity

Got my Lord Chamberlain his liberty.

I’ll tell you what: I think it is our way,

If we will keep in favour with the King,

To be her men and wear her livery.

The jealous, o’erworn widow and herself,

Since that our brother dubbed them gentlewomen,

Are mighty gossips in our monarchy.

Got my Lord Chamberlain his liberty.

I’ll tell you what: I think it is our way,

If we will keep in favour with the King,

To be her men and wear her livery.

The jealous, o’erworn widow and herself,

Since that our brother dubbed them gentlewomen,

Are mighty gossips in our monarchy.

BRACKENBURY

I beseech your graces both to pardon me.

His majesty hath straitly given in charge

That no man shall have private conference,

Of what degree soever, with your brother.

His majesty hath straitly given in charge

That no man shall have private conference,

Of what degree soever, with your brother.

RICHARD GLOUCESTER

Even so. An’t please your worship, Brackenbury,

You may partake of anything we say.

We speak no treason, man. We say the King

Is wise and virtuous, and his noble Queen

Well struck in years, fair, and not jealous.

We say that Shore’s wife hath a pretty foot,

A cherry lip,

A bonny eye, a passing pleasing tongue,

And that the Queen’s kin are made gentlefolks.

How say you, sir? Can you deny all this?

You may partake of anything we say.

We speak no treason, man. We say the King

Is wise and virtuous, and his noble Queen

Well struck in years, fair, and not jealous.

We say that Shore’s wife hath a pretty foot,

A cherry lip,

A bonny eye, a passing pleasing tongue,

And that the Queen’s kin are made gentlefolks.

How say you, sir? Can you deny all this?

BRACKENBURY

With this, my lord, myself have naught to do.

RICHARD GLOUCESTER

Naught to do with Mrs Shore? I tell thee, fellow:

He that doth naught with her—excepting one—

Were best to do it secretly alone.

He that doth naught with her—excepting one—

Were best to do it secretly alone.

BRACKENBURY What one, my lord?

RICHARD GLOUCESTER

Her husband, knave. Wouldst thou betray me?

BRACKENBURY

I beseech your grace to pardon me, and do withal

Forbear your conference with the noble Duke.

Forbear your conference with the noble Duke.

CLARENCE

We know thy charge, Brackenbury, and will obey.

RICHARD GLOUCESTER

We are the Queen’s abjects, and must obey.

Brother, farewell. I will unto the King,

And whatsoe‘er you will employ me in—

Were it to call King Edward’s widow ‘sister’—

I will perform it to enfranchise you.

Meantime, this deep disgrace in brotherhood

Touches me dearer than you can imagine.

Brother, farewell. I will unto the King,

And whatsoe‘er you will employ me in—

Were it to call King Edward’s widow ‘sister’—

I will perform it to enfranchise you.

Meantime, this deep disgrace in brotherhood

Touches me dearer than you can imagine.

CLARENCE

I know it pleaseth neither of us well.

RICHARD GLOUCESTER

Well, your imprisonment shall not be long.

I will deliver you or lie for you.

Meantime, have patience.

I will deliver you or lie for you.

Meantime, have patience.

CLARENCE

I must perforce. Farewell.

Exeunt Clarence, Brackenbury, and guard, to the Tower

RICHARD GLOUCESTER

Go tread the path that thou shalt ne’er return.

Simple plain Clarence, I do love thee so

That I will shortly send thy soul to heaven,

If heaven will take the present at our hands.

But who comes here? The new-delivered Hastings?

Simple plain Clarence, I do love thee so

That I will shortly send thy soul to heaven,

If heaven will take the present at our hands.

But who comes here? The new-delivered Hastings?

Enter Lord Hastings from the Tower

LORD HASTINGS

Good time of day unto my gracious lord.

RICHARD GLOUCESTER

As much unto my good Lord Chamberlain.

Well are you welcome to the open air.

How hath your lordship brooked imprisonment?

Well are you welcome to the open air.

How hath your lordship brooked imprisonment?

LORD HASTINGS

With patience, noble lord, as prisoners must.

But I shall live, my lord, to give them thanks

That were the cause of my imprisonment.

But I shall live, my lord, to give them thanks

That were the cause of my imprisonment.

RICHARD GLOUCESTER

No doubt, no doubt—and so shall Clarence too,

For they that were your enemies are his,

And have prevailed as much on him as you.

For they that were your enemies are his,

And have prevailed as much on him as you.

LORD HASTINGS

More pity that the eagles should be mewed

While kites and buzzards prey at liberty.

While kites and buzzards prey at liberty.

RICHARD GLOUCESTER What news abroad? 135

LORD HASTINGS

No news so bad abroad as this at home:

The King is sickly, weak, and melancholy,

And his physicians fear him mightily.

The King is sickly, weak, and melancholy,

And his physicians fear him mightily.

RICHARD GLOUCESTER

Now by Saint Paul, that news is bad indeed.

O he hath kept an evil diet long,

And overmuch consumed his royal person.

’Tis very grievous to be thought upon.

Where is he ? In his bed ?

O he hath kept an evil diet long,

And overmuch consumed his royal person.

’Tis very grievous to be thought upon.

Where is he ? In his bed ?

LORD HASTINGS He is.

Other books

The Power of Persuasion by Kate Pearce

The Quest by Olivia Gracey

Counter Poised by John Spikenard

The Scent of Pine by Lara Vapnyar

Maternity Leave by Trish Felice Cohen

Witch Fire by Anya Bast

The Art of Unpacking Your Life by Shireen Jilla

Quantico by Greg Bear

American Wife by Curtis Sittenfeld

The Road Back by Di Morrissey