William Falkland 01 - The Royalist (20 page)

Read William Falkland 01 - The Royalist Online

Authors: S.J. Deas

‘Until he turned up dead.’

There were tears shining in her eyes. I’d not meant to make her cry. I stepped forward, thinking I might put a consoling hand on her shoulder, but she shuffled back and left my hand hanging in the air.

‘They still distribute the pamphlets?’ I asked.

She nodded. ‘It went more slowly after Tom died, but yes. There’s a pamphlet tucked inside every pocket Bible and more besides.’

I could hear the children gathered in the hallway like dogs punished by their master, scrabbling at the door to be let in, all ready to grovel. I opened it and the flood of them almost swept me over as they came past on either side and even through my legs to get back to Mrs Miller. The oldest girl moved more slowly than the rest, considering me with a withering eye. I wanted to tell her: this isn’t my fault; I didn’t make your nanny cry; I didn’t throw her friend on top of a lit granadoe.

‘Mrs Miller,’ I said. ‘The printing press and the books, then, they are well known?’

She nodded. ‘Black Tom hisself has spoken of it.’

‘I will not tell anyone of

your

secret, that you bring these papers out of the old Fletcher house for your children to stitch. It is no concern of mine at all. But it’s not only the pocket books you stitch, is it? The pamphlets you have with you now with pictures of devils. They are not

The

Soldier’s Pocket Bible

. I will ask one thing, Mrs Miller: who is it who pays you? Who prints them?’

She was smothered by the children. They formed a protective guard around her. I had a terrible feeling I could have used a guard of my own. ‘I dare not say,’ she whispered.

‘Black Tom?’ But I saw at once that I was wrong. A ghostly tremor moved in my spine and the image of a face floated into my vision. It wasn’t a face I wanted to see. ‘This soldier. Does he have wild black hair? A strange kind of grace?’

Mrs Miller nodded. ‘You’ve met . . .’ She breathed a little sigh, almost one of relief. ‘Well, sir, you’d do well to pretend your paths never crossed. Edmund Carew might look a soft enough man, but meeting him is the biggest regret of my long, long life.’

CHAPTER 19

The house was silent when I got back. In the scullery, Kate Cain had some watery soup on the boil even though it was now the dead of night. She’d waited for me. Her face, still swollen, showed her bruises more darkly than I remembered. Still, she welcomed me fondly and stirred up whatever had settled at the bottom of the soup for me to have my fill. There was rabbit in there and it sat welcome and warm in my stomach. I made sure she ate as well.

‘Is Warbeck here?’ I asked her. Her glance to the ceiling was answer enough. ‘Kate, I must ask you a question.’

‘You can ask,’ she returned, ‘but I won’t promise an answer.’ She spoke with a smile.

‘They asked you to spy on me,’ I said. ‘That much I know. But I must ask you – have they asked you to spy on anybody else in this camp?’

The question seemed to throw her off guard. She’d been standing at the oven and turned, cautiously, with her green eyes twinkling behind her beaten mask. ‘I’m indebted to Black Tom. I’m indebted to Purkiss, even though it was his commands that did

this

.’ She gestured at the markings on her face and I winced, for shame. ‘Without what they pay me, I’d . . .’ She turned away from me again. ‘I’d be one of the Admonished, Falkland. A camp whore!’ After she barked out the word she seemed to wrestle with herself. At last she let out a deep sigh. ‘You already know, Falkland,’ she said more softly this time, coming to sit beside me. ‘All the men I keep here, I’m sworn to spy on them. There were others before. Now it’s you and Master Warbeck.’

‘I had thought,’ I said, ‘there might be others now.’

She shook her head slowly. We faced each other now and my legs formed a guard around hers. I took her hand. ‘What have you found, Falkland?’ she whispered.

I did not know. I had found – a story. A connection. The fact that Edmund Carew knew both Hotham and Tom Fletcher seemed much more than coincidence and I’m not a man who cares much for the vagaries of chance and fate. Perhaps I was that way once, but now there must be a reason for everything that happens. To admit there was no reason would be to admit that it was just cruel fate that took me away from my dear wife and children – and to admit that would be to admit nobody was to blame. I wasn’t ready for that.

‘Have you seen this?’ I asked. I let go of her hand though she seemed unwilling and it took me a lingering moment to tease my fingers free. From my pocket I produced the pages of the pamphlet I’d stolen away from the children of Mrs Miller. ‘The dead boy Tom was distributing it.’

She looked at the pages for only a moment before she handed them back. ‘Falkland,’ she said. ‘It’s incomplete.’

‘Incomplete?’

When she didn’t quickly reply, I faltered. She shuffled away from me and looked shamefaced. ‘Falkland. I don’t know what the pamphlet says because I cannot rightly read.’ She paused. ‘Don’t look at me like that. I’m no lady of letters, but I’ve never pretended to be. I’m a servant, Falkland. To men like you

.

’

‘You have me wrong,’ I said. ‘I’m a farmer.’

‘A farmer?’ She snorted: ‘Perhaps you were a farmer once, Falkland, but look at you now! You’re an intelligencer for Oliver Cromwell himself! You’ll never be a farmer again. A common man might rise to be a politician but he doesn’t return to the land.’

Perhaps she was right but it was a terrible thing to know that this, now, was how the world looked on me: not as a farmer, lost in the city as I once was; nor as a common soldier, pressed into service and rising, however unwillingly, through the valour of combat. I was a man in the employ of the nation’s oppressors. I could barely stand it to think that an honest, decent woman such as Kate would see me in such a way.

She took my hand again, gently, perhaps sensing the loathing I felt for myself in that moment. ‘The pamphlet,’ she said. ‘Might it mean something to your investigation?’

I nodded. ‘I’ve a terrible feeling it might mean everything.’

‘In that case, Falkland,’ she said, drawing herself high, ‘I cannot tell you what is in the missing pages . . . but perhaps I can show you the pages themselves.’

She led me up the stairs. They creaked and complained underfoot but we took them lightly for we were not alone in the house. At the top was the small room with the single pallet where Warbeck laid his head when he passed the night here at all. In the second room, Miss Cain slept. Now she led me through that door. The windows were shuttered and the air thick with motes of dust but she lit a candle that spread fingers of light across the room. Against one wall there stood a bed, dressed down with blankets folded at the end, and against a wooden chair stood a scabbard with no blade inside. An embroidery hung on the wall, a biblical verse picked out in black stitches with flowers growing up and down the frame. Caro had one just the same, a work she’d slaved over as a young woman and expected to pass to our daughter and our daughter’s daughter for generations to come. Standing here I felt as if I was at the frontier between a long, happy past and a long, uncertain future. This had been Miss Cain’s family’s home once; come the spring, perhaps there would be no family to survive.

‘Shut the door,’ she said.

I did as I was told while Miss Cain skirted the bed and lifted her hems and knelt to open a chest around the other side. In it were folded clothes, some tied with string. I saw a green tunic, a woollen shawl, a dagger buckled inside a glittering scabbard. These, I deduced, were family trinkets, things she’d somehow managed to deny the New Model. On top of them all were pieces of crumpled paper.

‘Here,’ she said. She smoothed them and passed them to me across the stark bed. I took them. My fingers touched hers. We held the pose.

She let go of the pamphlet but I let go of it too and it fluttered onto the bed between us. ‘I was the King’s man,’ I breathed. I could hardly force the words out. ‘Not Cromwell’s. But I spoke up against my King once. Believe it or not it’s the reason I’m here. Cromwell told me he needed a man of good conscience in a place like this. He did not mean Crediton. He meant the New Model.’

There seemed a new spark in her eyes. ‘What did you do,’ she began, ‘to speak up to your King?’

‘I had a man hanged,’ I said, refusing to swallow the words however ugly they seemed. ‘A ravisher. I did as Cromwell would have done, though the King told me not to. I thought afterwards that I might lose my head for it but at the time I didn’t care. I didn’t want to serve a king who saw it fit to let his soldiers . . .’

My voice was trembling. Those days in Yorkshire would always be a part of me. They had, I thought, been directing my movements ever since. Had I been a coward that day and done as my King expected then I would have been hanged at Newgate. There would have been no reprieve. I wanted to think it would have been better that way but I couldn’t. And it wasn’t because I was thinking of my wife. It wasn’t because I was thinking of my son John and my daughter Charlotte, no matter how much I loved them. It was because I was here in this room, staring at Miss Kate Cain with her short black hair and her emerald eyes, studying the crumpled contours of her face where the soldiers had taken to her with their fists.

‘I would hang them for hitting you,’ I quaked. ‘Purkiss and whichever men he brought with him. Fairfax for sending them to do it. I’d hang them up in the town square. I’d draw and quarter them.’

‘Falkland,’ she whispered. ‘

William . . .

They did not . . . They did no more than you see. Purkiss and his sort, they’re not good men but nor are they bad. They’re simply men.’

She reached down and picked the pamphlets up from the bed and handed them back to me. ‘I found them in the scullery of the Fletcher cottage as I made my way out. I waited for you. I tried to give them to you. I thought . . .’ When I took them I felt her fingers again. This time I clasped her wrist with my hand and she didn’t resist. I moved forward, one knee on top of the bed, and she mirrored the movement on the opposite side. We were so close that I could feel the warmth of her breath, her lip dark and bulging where a soldier’s hand had struck her. My own hand danced up her arm until I softly stroked the marks. She winced as my touch feathered her but stopped herself from retreating. With my other hand I cupped the back of her head. Her hair was like down, like the soft fur that topped my daughter’s head on the day she was born.

My lips were almost with hers when I drew quickly away. I rose, the pamphlet scrunched in my hand, and hurried to the door. I stood on the threshold. Her words, I thought, might have described all the thousands of men that made up this New Model: not one thing and not another; not good and not bad; neither roundhead nor cavalier.

‘He would be a bad man if I found him now,’ I admitted, turning to take another lingering look at her, still hovering over the bed. ‘Miss Cain, I beg your forgiveness.’

I turned and walked the passageway and down the stairs, back to the sanctity of my own room – but as I went I couldn’t keep myself from hearing, over and over again, the whispered words that followed me. ‘Falkland,’ she said, ‘there’s nothing to forgive.’

I lay alone for hours after that, unable to sleep and yet unable to bring myself to read the pamphlet in my fingers. I didn’t hear anything thereafter. I supposed Miss Cain had gone to her bed for the night was already long in the tooth. Yet whenever I closed my eyes I imagined a different night. Catching myself dreaming of it was a curious form of punishment, like being outflanked by two opposing armies with no possibility of escape. The fleeting images I had of Kate, pinned underneath me or else arching above, were a torment themselves; but a torment greater still were the pictures that punctuated them – of the country church where I was wed to my Caro, of the grey afternoon when I was summoned with weary joy by the midwife to be introduced to my firstborn son.

I must have lain there for an age before the pictures ebbed away and left me. It wasn’t only a weariness that assailed me. It was a foreign kind of empty desolation. I skirted the edge of sleep but it wouldn’t take me. I got to thinking I was less a man than I was a ghost already. I walked in a world that wasn’t my own. I had no allegiances. I had no great love nor great hate for the people I had around me. I was an island. And then, very slowly, my thoughts returned to the boys: to Richard Wildman and Samuel Whitelock, to Tom Fletcher and even Jacob Hotham who stood apart from the rest, a roundhead strung up just the same as those poor cavaliers. Something bound these boys together. At last I heaved myself up from the bed and drew close to the guttering candle. In the dead heart of the night I unfolded the papers Kate had brought for me and assembled them into the pamphlet they were meant to be.

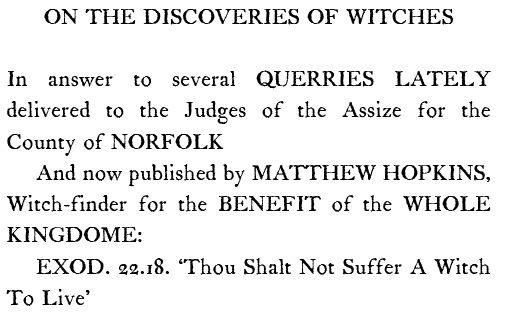

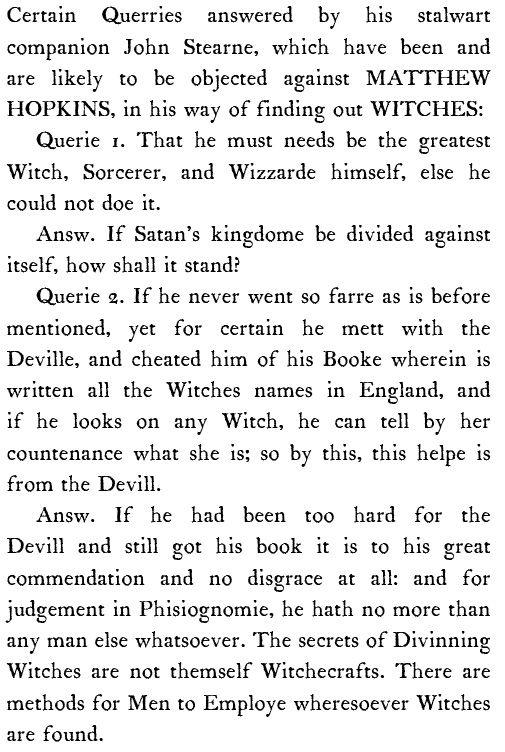

On the front was the familiar woodcut drawing of the malevolent face in the flames. Inside were the passages I’d already read – the oaths of allegiance, carefully rewritten to omit Parliament’s allegiance to the divinely appointed King; the proclamation of Boy’s death, so mockingly worked up with NECROMANCY and DEVILL in bold lettering. At the centre of the pamphlet was a discourse I’d not yet seen. It drew my eye instantly. At the top of the page were the words ON THE DISCOVERIES OF WITCHES. The lettering beneath was small and dense with only odd words leaping out of the page: POPISH WICKEDNESS and INCARNATE SOULDIERS were only the most prominent of a dozen and more such phrases.

I read from the top:

I had a feeling like Hell itself in my stomach. It wasn’t the soup Miss Cain had served nor my tempestuous carnal imaginings. I’d not heard of this Matthew Hopkins before, nor of any man fool enough to name himself witch-finder, but I’d heard the word right enough. My father once taught me that the worst devils are the devils that men make up. It’s not lore that any churchman or nobleman would suffer gladly, but there was wisdom enough in it. This wasn’t the first time I had heard of witches or witchcraft around this camp. It was what Kate had thought of me when Fairfax had brought me to her door.

There was more. Much more. The type was so tiny that I fancied it made up almost half of the pamphlet even though it was only printed on its innermost leafs. It wasn’t a surprise to me to know that men like this Hopkins, styling themselves the vanquishers of devils, might be abroad in the kingdom as it faltered. There will always be men to prey on the superstitions of the weak and never more than in a time of war. What gave me the strongest feeling of foreboding was a question for which I could not have an answer: why did Hopkins’ pamphlet form a part of this work put together by New Modellers? What did Carew and Hotham have to gain by distributing his message around the camp?