Will Eisner (26 page)

Authors: Michael Schumacher

Eisner’s self-portrait appeared in the Kitchen Sink Press series of “Great Cartoon Artists” buttons, issued in 1975. (Courtesy of Denis Kitchen)

He hadn’t seen any underground comix prior to attending the New York Comic Art Convention in 1971, but he’d heard more than enough about them to spark his curiosity.

Something

was happening, and it was happening away from New York, Eisner’s home base and the traditional epicenter of comics operations. Marvel and DC were still at the top of the charts in terms of sales and influence, but they were earning their keep in the superhero game, even if such young writers and artists as Dennis O’Neil and Neal Adams were pushing the boundaries of superhero entertainment by adding heavy doses of social consciousness to their work. Eisner wanted no more to do with creating superheroes than he had while he was working on

The Spirit

. From everything he’d heard, the undergrounds were entirely different, from the topics they addressed between their colorful covers to the way they were being marketed and distributed. They had

shelf life

. They weren’t being issued every month or so, only to be pulled from the racks and replaced when a new issue came out. They stuck around until they were sold, and in the cases of really successful ones, additional printings were issued. This was radically different from anything Eisner had ever experienced.

He’d heard of Denis Kitchen and his continuously expanding operations, Krupp Comic Works and Kitchen Sink Enterprises, which in just a few years’ time had grown from publishing a handful of titles per year to moving into merchandising and recording. Robert Crumb, the most recognizable name in comix, was publishing regularly with Kitchen; his

Home Grown Funnies

had been Kitchen Sink’s first bestseller. When Eisner learned that Kitchen was attending the convention, he asked French comics historian Maurice Horn to set up a meeting. Horn ran across Kitchen in the dealer’s area of the convention floor, rifling through old comic books. “Will Eisner wants to meet you,” he announced.

Kitchen wouldn’t have been more surprised if he’d just heard that a head of state was requesting a private audience. Kitchen knew Eisner more by his reputation than by his work, but that was more than sufficient for him to know that he should be the one requesting a meeting, not the other way around.

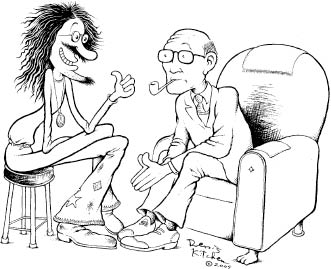

Eisner and Kitchen met in a hotel room, where they could talk without interruption or having to shout over the din of the convention floor. Kitchen, in a ruffled shirt, purple tie-dyed pants, and tan corduroy jacket, and Eisner, in his gray three-piece suit, were the generation gap personified. It didn’t take long, however, for both to realize that their interest in each other’s work and experiences in comics transcended their age difference. Kitchen, quite naturally, wanted to know all about Eisner’s exploits in the Golden Age of comics and about his work on

The Spirit

. Eisner had other interests. Through Phil Seuling, he had been briefed about Kitchen’s operations, of the way he distributed his comix on a no-return policy, how he paid royalties to his artists (as opposed to flat page rates), how he returned all the original art to the artists, and how the artists retained their copyrights. All this differed from the way the big companies conducted business, and Eisner, who was toying with the idea of starting his own magazine of

Spirit

reprints, wanted every bit of information Kitchen could supply. Eisner, Kitchen determined early in their conversation, had little interest in talking about his past. He would politely answer a question or two about the old days, then redirect the exchange back to the present and, ultimately, the future.

Bridging the generation gap: Denis Kitchen created this sketch of his first meeting with Eisner in 1971. The two became close friends, working together from their initial meeting until Eisner’s death in 2005. (Courtesy of Denis Kitchen)

“I was impressed,” Kitchen noted later. “This straight-looking fellow seemed to be a kindred spirit. I had been under the impression, like the rest of the industry, that Eisner had more or less retired from comics. In retrospect, we couldn’t have been more wrong.”

Eisner later admitted that he, too, had to dismiss his first impressions.

“To a buttoned-down type like me, this should have sent me running in the other direction,” he said of his initial impressions of Kitchen. “However, it didn’t take great genius to see that what was afoot was a reprise of the frontier days of 1938.”

The more Eisner heard, the more he appreciated what the undergrounds had to offer. In the past, he’d always had to conform, one way or another, to firms purchasing his work, whether it was Fiction House buying work from Eisner & Iger or the Sunday newspapers picking up

The Spirit

supplements. The army had rigid restrictions for

P

*

S

magazine, and his bosses there wouldn’t have considered returning his art. For all he knew, it was being destroyed as soon as the magazine appeared. Eisner and Kitchen talked and talked, and when Eisner eventually admitted that he had never actually seen one of these underground comix, Kitchen offered to take him back to the convention for a look. Kitchen was thrilled. When he’d left Wisconsin for the East Coast, he couldn’t have predicted in his wildest fancies that he would be making friends with one of the most influential figures in comics history.

Unfortunately, the Eisner-Kitchen meeting ended abruptly, and on less than favorable terms, when Kitchen walked Eisner to the dealer area, to a grouping of several long tables stacked with nearly every underground book on the market. Kitchen intended to select a few titles that Eisner might appreciate, but before he could do so, Eisner reached down and grabbed a copy of

Zap

, which contained one of the most over-the-top shock entries in early comix history, an S. Clay Wilson number,

Captain Pissgums and His Pervert Pirates

, in which a pirate cuts off the tip of another pirate’s penis and proceeds to eat it.

“Will saw it and he just blanched,” Kitchen remembered. “I mean, he was virtually speechless. As I recall, he started to stutter. I said, ‘This isn’t exactly typical.’ He said, ‘I had no idea they were this strong.’ There were fans standing nearby—fans who recognized Will—but there was also a very young and virtually unknown Art Spiegelman, and as soon as he saw Will start to harrumph about these undergrounds, he stepped in to try to defend his buddies.”

Eisner had no interest in engaging in a public debate with Spiegelman or anyone else over the merits of the undergrounds. If this was the type of material published by the underground publisher, he wanted no part of it, regardless of how the business was run. Maybe the generation gap was too much to overcome. Rather than continue the conversation, he politely excused himself and left the convention. To Kitchen’s dismay, he didn’t return.

Given Eisner’s age and background, it isn’t difficult to understand why he might have been offended by the Wilson comix feature. Nor is it difficult to determine the appeal of comix to the underground artists and their readers. In the rebellious decade between 1965 and 1975, when the undergrounds took root, thrived, and eventually lost some of their impetus, the Comics Code of Authority stamp of approval stood nakedly in the world of comics as the ultimate symbol of the Establishment. Following the implementation of the code, comic books issued by the big publishing houses had been reduced to pabulum. With only an occasional exception, such as the Dennis O’Neil and Neal Adams

Green Lantern/Green Arrow

contributions to DC, or a Steve Ditko or Jack Kirby story about one of Marvel’s conflicted superheroes, comics had no heart and soul. They could be accomplished in their artwork, but their stories were vapid and their heroes predictable.

Stan Lee, though mainstream in his subject preferences and a good company man while working for Marvel, was intrigued by the popularity of the undergrounds. There was obviously a market for this new anti-Establishment material and money to be made. In 1974, he would approach Denis Kitchen and enlist his services in the production of a new Marvel title,

Comix Book

, but the title had no chance. The magazine-sized hybrid, a kind of cross between the undergrounds and

Mad

magazine, lasted only three issues at Marvel. Lee admired some of the work of a few comix artists, but, like Eisner at the convention, he had no tolerance for the excesses. “To be successful, they had to be outrageous and dirty,” he said. “I didn’t want to be dirty, so I abandoned it.”

The excesses, of course, were precisely what attracted readers to the undergrounds. To teenagers and young adults schooled in the hurricane mixture of rock ’n’ roll, radical politics, free and open drug use, and casual sex, the more excessive the comic book could be the better. There was no room for compromise in a country engaged in an extremely unpopular war, where political assassinations destroyed any faith they might have had in their futures, where a dissident voice might be silenced by law enforcement officials using petty drug busts and subsequent incarceration as a means of eliminating protesters. The undergrounds, sold in head shops next to black-light posters, rolling papers, and tie-dyed T-shirts, were further endorsements of their lifestyles. Freedom of speech, although wounded, wasn’t dead.

Robert Crumb, who preferred to use only an initial for his first name when signing his work, was nothing less than a god in the underground canon. Crumb had loved comics as a kid, and along with his brother Charles, he had created comics as a teenager, including a series of adventures involving a cat named Fred, later renamed Fritz. Suave, fast-talking, and oversexed, Fritz the Cat was just about everything Crumb was not. Harvey Kurtzman, editing

Help!

magazine after his stint with

Mad

, saw the feature when Crumb moved briefly to New York, and he gave Crumb a job at the magazine, working as an assistant for future filmmaker Terry Gilliam. Crumb, however, was too peripatetic by nature to stay at any job for long, and his tenure at the magazine was brief.

Crumb had actually tried living in a more traditional American way, when he married and worked as a card designer for the American Greetings Corporation in Cleveland; but he wasn’t happy. He abandoned that life without warning, leaving his wife and job behind and taking off for the West Coast, where he found a receptive culture in San Francisco’s Haight-Ashbury district. Drugs—particularly LSD—gave him a new perspective on both his life and his art. “All the old meanings become absurd,” he said later, long after his name had become synonymous with comix, “so it heightens your sense of the absurdity, or mine, anyway, of all the things you’re taught or programmed to believe is important or significant about reality, so that it made it easier to poke fun at everything.”

Crumb could have scoured the entire country and he wouldn’t have found an environment more receptive to his art. The Bay Area, historically tolerant and freewheeling in its thinking, loved its eccentrics, misanthropes, antiheroes, outlaws, tricksters, pranksters, dissidents, and radicals. Peter Fonda’s Captain America was a far better fit than the Jack Kirby/Joe Simon comic book hero by the same name, and Crumb’s Mr. Natural, with his long hair, waist-length beard, and totally laid-back demeanor, was far more interesting than a tights-wearing, muscle-bound superhero defending truth, justice, and the American way. Crumb’s characters had huge feet and big butts, legs like tree trunks, and overall physiques that seemed like polar opposites of the glamour cultivated by Hollywood a few hundred miles to the south. They were hairy as hell, smoked lots of pot, and jumped in the sack whenever the mood struck—which was often. Crumb urged his readers to “Keep on Truckin’” at a time when America was rocketing to the moon. His album jacket art for Big Brother and the Holding Company’s

Cheap Thrills

attained iconic status before Janis Joplin’s boozy blues voice had reached the ears of the young folks in the hinterlands.

Crumb inspired other comic artists and countless imitators, but lost in the hoopla was the fact that, whatever his image, he worked like a demon, more out of necessity than the Muse’s constant calling. There still wasn’t much money in comics—and especially not in the underground variety—and living on the West Coast wasn’t cheap. Fortunately, there was a steady demand for Crumb’s art, much of it in the Midwest, where publishers like Denis Kitchen, Jay Lynch, and others coveted Crumb’s latest work. In San Francisco, Crumb produced his own titles and hauled them around the city in a baby buggy, selling them to people on the streets.