Wild Hares and Hummingbirds (28 page)

Read Wild Hares and Hummingbirds Online

Authors: Stephen Moss

Baby moorhens are even more appealing: little black balls of fluff with a hint of the adult’s red and yellow around their head and bill, and hilariously out-of-proportion feet. As they fledge, they turn into one of the gawkiest juvenile birds of all – a classic example of a cute baby turning into an awkward teenager – before finally attaining the subtle allure of the adult.

The name moorhen is, when you think about it, rather puzzling. It is actually a corruption of ‘mere-hen’: bird of the meres, or shallow lakes. It has occurred to me that the name for this part of the world, the Somerset Moors and Levels, may also have derived from this same root: ‘meres and levels’ certainly makes more sense in this flat, wet landscape. Local names for the moorhen include ‘water hen’, while a Somerset name no longer in use, ‘skitty hen’, refers to the bird’s habit of dashing off across surface vegetation when disturbed, as I have just witnessed.

Further along Vole Road there is a much smaller baby moorhen, just a few days old and now faced with a race to grow before the autumn frosts make food more difficult to find, reducing its chances of survival. A kestrel flies low overhead, causing the chick and its parent to panic. Imagine what it must be like to live in this steep-sided rhyne, the only view a grassy bank on either side, and the sky above; a sky which can bring danger, even death, at a moment’s notice. No wonder the mother moorhen looks so nervous.

A

WEEK OF

rain towards the end of the month has produced a small, muddy puddle in the corner of the field behind our home. Despite the competing attractions of rhynes, ditches and, not so far away, lakes, the five cygnets that hatched out here at the end of June have

chosen

this as their playground. Under the ever-watchful eyes of their parents, they wallow and splatter about in the mud. This makes little difference to their appearance, as they still sport the deep, dirty grey of the proverbial ugly duckling. I am delighted, and not a little surprised, that the five have all survived, given the dangers they face. The parents have obviously done a good job guarding their precious offspring.

Autumn is beginning to show its face around the parish, like an unwelcome intruder getting ever more confident as each day passes. Mornings are cooler now, and sometimes quite misty, with the plaintive autumn song of robins flowing through the quiet. Evenings see little flocks of starlings passing overhead, occasionally stopping off to land on our roof, where they cause consternation among the resident sparrows.

Another sign of autumn: a small cluster of creamy objects on the otherwise green lawn. Three fungi: four or five inches tall, with long, slender stems and jagged-edged flat caps. On closer inspection I can see the subtlety of their colour: the cream cap is splattered with brown, shading more intensely towards the shallow dip in the centre, while beneath the cap the gills are yellowish-buff, and pleasingly soft to the touch. I sniff one, and get the whiff of a delicate mushroomy smell not very different from the shop-bought version. But given my lack of fungal expertise, I decide that prudence is the better part of valour, and I am not tempted to take a bite.

Families of goldfinches, the youngsters lacking the adults’ red faces, gather on the heads of thistles to feed, while swallows and house martins perch on the telegraph lines around the village centre, as if taking an inventory of their numbers before they depart. I shall miss them when they go.

On a clear night, at the start of the August bank holiday weekend, a full, round moon reflected in the long, straight rhyne turns oval in shape. This is caused by the unseen movements of small aquatic creatures just beneath the surface, making the waters ripple, and distorting the heavenly body above.

SEPTEMBER OPENS WITH

a cool, bright, misty morning. The dampness in the air is palpable in the hour after dawn, but soon burns off as the sun strengthens in the early-autumn sky. Phalanxes of swallows rise high in the air, the juvenile birds, with their short, stubby tails, testing their wings. I watch each day as they venture higher and higher, until they seem to reach the vapour trails of departed aircraft, growing fuzzy in the blue. From this aerial vantage point, the swallows can see into the next parish, and perhaps beyond, to Glastonbury Tor. But they cannot imagine what awaits them when they finally leave us, and the globe begins to unfold beneath their wings as they head south to Africa.

A pair of larger, darker birds passes swiftly overhead. From directly beneath, the falcons’ streamlined, swept-back wings, dark helmets and streaked underparts mark them out as something special. They are hobbies: a sleek sports car to the kestrel’s family hatchback. Like the swallows, these are young birds, not only testing out their flying skills, but their hunting abilities too. But this time, at least, the swallows are too quick for them, and they move on, their sleek arrow-shapes passing rapidly out of sight.

Soon afterwards, an adult hobby flies low overhead, seeking the benefit of surprise to nab a young swallow. But the parent birds are well aware of the danger, and pursue the falcon relentlessly. They take turns to peck at

its

back and tail with their sharp bills, until it is driven away, their urgent twitters of alarm echoing in its wake. It’s easy to assume that predators have the upper hand in any encounter with their prey; but these attacks fail more often than not. And at some point the hobby must make a kill; for it, too, has a long journey ahead, all the way to the wide open savannah of the Zambezi River basin. There it will spend our winter hawking for insects – and the occasional swallow – before returning to the skies of Somerset next April.

It is still cool at this early hour, and steam is rising from my neighbour’s compost heap. But one band of insects, the dragonflies, are already out and about, hunting their own prey with an equally ruthless efficiency. Ironically, dragonflies are often taken by hobbies, which have developed the ability to pursue this fast and furious insect, grabbing them in mid-air with their claws, before dispatching them with their hooked beak.

But today, the migrant hawker dragonflies are the predators, not the prey. They patrol just above the tops of the bushes and trees, dinking left, right, up, down, and sideways, on their wonderfully manoeuvrable wings, and grabbing any passing insect from a fly to a bumblebee with those fearsome jaws. Later in the day, as the sun warms the bramble bushes, I catch sight of one of these elegant creatures as it basks in the warm rays, its abdomen a delicate combination of brown, yellow and mauve. As its name suggests, the migrant hawker was once only a

seasonal

visitor to our shores. But in the past few years it has colonised southern and eastern Britain, and is now a familiar sight here in the parish during late summer and early autumn.

N

OW THAT

S

EPTEMBER

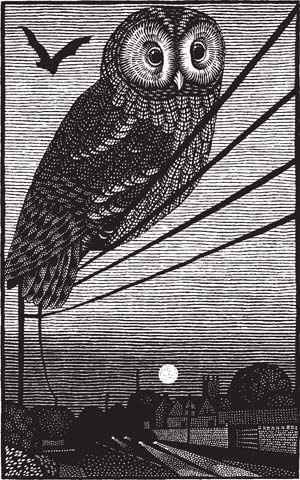

is here, the nights are gradually drawing in. By 8 p.m. the sun has set, and the sky is almost dark. Outside the Old Vicarage, a hundred yards or so east of the village shop, a bird is perched on the telegraph wires: those same wires where, a few months ago, the first swallow of the summer was sitting.

The bird is a tawny owl. It sits on the topmost wire, unnoticed by drivers passing beneath on their journey home from work. Occasionally it twists its head slowly from side to side; though even when a medium-sized bat passes close by it takes no notice. After a few minutes, it drops off the wire on soft, silent wings, disappearing into the dense foliage of a nearby sycamore. In an hour or so, when the remaining glimmer of light has finally been enveloped by darkness, it will go hunting, listening for the rustling of hidden rodents below.

Here in the village, tawny owls are not uncommon; yet, given our many regular breeding birds, this is the one we see least often. We hear them though, as they call to each other, famously chronicled by Shakespeare in

Love’s Labour’s Lost

:

Then nightly sings the staring owl

Tu-whoo!

Tu-whit, tu-whoo! A merry note!

Shakespeare, who was usually pretty accurate in his bird references, makes an elementary mistake here. For this sound is not made by a single owl, but by a pair, performing in tandem. Thus the female calls ‘kee-wick’, while the male utters the more familiar, hooting call.

From early autumn onwards, I hear the hooting male more than any other time of year. This is a signal that the youngsters, born the previous spring, are now trying to establish their own territories for the breeding season to come. Because tawny owls like their own patch of ground – they rarely stray more than a few hundred yards from where they were born – the parent birds are forced to defend their little patch of land against their own offspring. This explains the increase in hooting on cold autumn nights.

And even, on occasion, during the day. Two or three times every autumn, at about eleven o’clock in the morning, I hear a tawny owl hooting from the garden next door. The first time I thought my ears were playing tricks on me. But so strong is the impulse to defend its territory against incomers that our neighbourhood male does indeed hoot during daylight hours.

During the autumn and winter, I sometimes come across a tawny owl at its daytime roost. These are never

easy

to find: an owl is surprisingly well camouflaged, despite its size, and can sit motionless in a hollow of a tree for hours on end, hidden to the world. Hidden, that is, until discovered by a curious passing bird. Then the unfortunate owl will find itself hassled from all sides, as the smaller birds join forces to see off this unwelcome predator. Usually the owl will tolerate the intruders until they back off, but if the harassment gets too much, it will be forced to move on and seek alternative daytime accommodation.

But they never go far: unlike the swallows, currently massing in the skies above the village shop, the tawny owl next door will never even see the next village, let alone Africa.

T

HE NEXT MORNING

, a sheet of mist hangs low over the distant Mendip Hills, as an unseen buzzard mews in the far distance, towards Chapel Allerton. Thick, heavy dew soaks the grass, the hedgerows and my feet, and I notice another sign of autumn: the teasels that only a few weeks ago were a delicate greenish-purple are now a rich, warm chestnut-brown. The willowherb has gone to seed too: fluffy balls of grey fur where once there were purplish-pink flowers.