Wild Hares and Hummingbirds (22 page)

Read Wild Hares and Hummingbirds Online

Authors: Stephen Moss

Who would have thought that within ten years the small tortoiseshell, rather like the house sparrow, would have become a creature we now notice because of its scarcity, rather than one we ignored because of its ubiquity?

E

VERY MORNING AND

evening, during the village rush hour, if such a thing exists, our neighbours at Perry Farm drive their cattle the short stretch along the road to and from their pasture. The animals wander slowly towards the gate, by the sharp left-hand corner which marks the north-eastern border of our parish.

Every morning, and every evening, the cattle do what cattle do. And once the day’s traffic has passed up and down, the cowpats are spread across the road like a thin layer of Marmite. Just before dusk falls, thousands of tiny insects gather to feed on the dung, while a brood of newly fledged pied wagtails comes to feed on the insects. They flutter back and forth on their new, inexperienced wings, taking advantage of this food bonanza.

Meanwhile, a pair of swans is sitting in the field just behind the small ditch by the entrance to Perry Farm. The male and female are guarding five small, fluffy cygnets – each well over a foot long – which hatched out only a few days ago. The original ugly ducklings sit, flanked by their proud parents, among piles of white, downy feathers. As I pass, on my cycle ride home, the male lowers his neck and hisses aggressively. I pray that he and his family pass a quiet night, with no visit from the local fox.

I realise, as I pedal the last short stretch back home, that half the year has gone.

JULY IS A

month of stasis rather than dramatic change; a chance to reflect on the roller-coaster ride of the spring, and look ahead to the coming autumn. April was full of activity, as migrant birds arrived back in the parish from Africa, adding their voice to the resident chorus. Sunny days in May saw an onrush of wild flowers and butterflies; while on warm June nights huge and colourful hawkmoths, and dark and mysterious bats, emerged from their daytime hideaways.

Soon, in August, swifts will pass overhead, flying purposefully south; and by September the swallows will gather on the telegraph wires, as red admirals bask beneath our cider-apple trees, enjoying the last warm rays of sunshine. But for now the whole scene is dulled by the lazy heat of long summer days. Even the dawn chorus is over: the tuneful orchestra that woke us each morning replaced by the incessant chacking of jackdaws, the plaintive cries of our neighbour’s peacocks, and a distant, mournful wood pigeon. There’s a good reason for this lapse into near silence. Now that the hard work of raising a family is over, the parent birds are hidden away in thick foliage, moulting into a brand-new set of feathers, in preparation for the colder weather to come. The youngsters are lying low, too, keeping out of sight to avoid the attentions of the local cats and sparrowhawks.

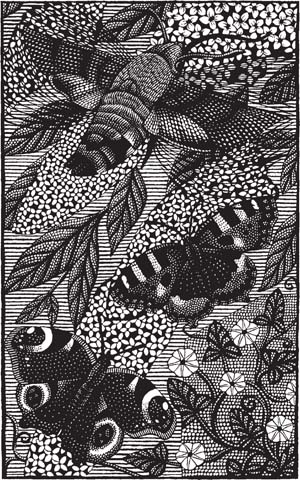

My own attention has turned from birds to their smaller flying counterparts. July is the peak month for

butterflies

and moths, bumblebees and hoverflies, all making the most of abundant nectar in the hedgerows and flower beds around the village. As I make my way slowly along the wide and bumpy droves, I am accompanied by a constant hum; the sound of millions, perhaps billions, of insects, as they live out their brief lives among us in this quiet country parish.

O

F ALL THE

insects that buzz, hum and flutter along the lanes, one of my favourites is the gatekeeper butterfly. Also known as the hedge brown, this alluring creature is a smaller and more elegant version of the widespread meadow brown butterfly. I am always struck by the brightness of the first gatekeeper I see: like the dust jacket of a brand-new book, the browns and oranges glowing in the summer sunshine. On sunny days in late July I have watched as the adults emerge en masse, dozens of them thronging the rhynes, before fluttering away to distant fields and gardens.

The gatekeeper’s name refers to its habit of loitering alongside footpaths by the edges of fields, often close to stiles or gates. For the butterfly, this is the perfect place to live: with plenty of brambles, on whose small white and yellow flowers the adults feed; and patches of cock’s-foot, fescues and other grasses, where they can lay their tiny, ivory-coloured eggs.

Like the meadow brown, the gatekeeper has two

prominent

‘eyes’ – one on each forewing – to confuse predators. On seeing the ‘eye’ a hungry bird may be fooled into pecking at the butterfly’s wingtip rather than its body, which is why in late summer I often see both meadow browns and gatekeepers with part of their wingtips missing. Better to have a wonky flight-path than be dead, I suppose.

The third butterfly in the ‘brown trio’, the wall brown, was once a common sight on the Somerset Levels, but since the 1960s has more or less disappeared. As with so many other iconic grassland species, from the skylark to the cornflower, this is a result of half a century of so-called agricultural ‘improvement’. The constant striving for higher yields, which can only be achieved by spraying the crops with a cocktail of pesticides, insecticides and herbicides, has turned much of lowland England into a sterile green desert.

Some creatures do still manage to hang on: on warm July days I have seen the marbled white butterfly, which, despite its name, is another member of the ‘brown’ family. Like its relatives, the marbled white is dependent on rough grassland, its striking piebald pattern easily picked out as it flits across the meadows in the midday sun. I have even seen marbled whites fluttering along nearby motorway verges, one of the few areas of grassland to escape the chemical onslaught.

F

OR THE LOCAL

farmers, it has been a good year so far. In wet summers, the second crop of silage is sometimes not cut until the end of August; but this year the first crop was taken in early June, and now the grass is growing, albeit slowly, for the second crop. Perversely, after praying for – and getting – fine weather, my farming neighbours are now hoping it will rain.

Along the lanes, many of the verges have already been shorn of long grass, cow parsley and hogweed. Flocks of birds gather to feed on the spilt seeds: chaffinches and goldfinches, the odd reed bunting, and a pair of stock doves, all fly up as I walk past.

As a herd of cattle grazes slowly along the banks of the Perry Road rhyne, just two weeks after the summer solstice, I see the first sign of autumn. A small flock of birds passes overhead, heading directly south-east. Starlings: about forty of them, flying towards the RSPB reserve at Ham Wall. By late November, millions will descend on the reserve each evening, whirling through the darkening sky and delighting the watching crowds.

Although it is long before sunset, and swallows and swifts are still flying overhead, I still get the sense that the year has turned. The nights are gradually drawing in, and we are now nearer the end of the year than the beginning. The story of the parish and its wildlife, which until now has been one of anticipation, arrival and birth, has begun its gentle slide towards decline, departure and death.

Only

then, in another turn of nature’s wheel, will there be a rebirth.

I

N THE GARDEN

, I see more signs of autumn. The first tiny, rock-hard apples are beginning to form: lime-green in colour, and still a long way from being eaten, cooked or turned into cider. Meanwhile, the hogweed is in rapid decline, its once creamy flower-heads now gone to seed. The meadow is awash with bindweed, its bell-shaped flowers forming a pleasing splash of white in the brownish-green landscape. Most gardeners despise this rampant flower, known as ‘devil’s guts’ for its ability to propagate itself from the smallest fragment of root, but botanical writer Geoffrey Grigson took a more benevolent view:

Neither blasphemy, hoeing, nor selective weed-killers

have yet destroyed it. One should speak kindly of its

white and pink flowers, all the same

.

On sunny days the bindweed is visited by hordes of humming and buzzing insects. And another sound has been added to the summer soundtrack: the long, rough grass is filled with the calls of tiny field grasshoppers, which bounce all around me as I pass along the garden.

I’ve only just noticed that the brief season for

elderflowers

is already over, the flower-heads rapidly darkening as they begin the process of turning into berries. I remember my mother and I collecting the soft, creamy blossoms, steeping them in boiling water, adding a pinch or two of yeast and bottling the liquid in huge, gallon-sized flagons. These would be left in the under-stairs cupboard until autumn, when a cloudy yellow liquid the colour and consistency of urine would be checked, filtered, tasted and eventually pronounced to be an acceptable alternative to warm Liebfraumilch, the main drink of choice in those days.

Later in the summer, towards the end of August, we would collect the elderberries, too; heavy purple bunches, crushed between our palms to release their deep magenta juice. I was never tempted to eat them – they were said to have a foul and bitter taste – but they did make a deep red wine. Nowadays, even the cheapest supermarket plonk would probably taste better, but it’s a pity that our modern drinking habits have lost the connection with the land, and its bounty, that my mother’s generation took for granted.