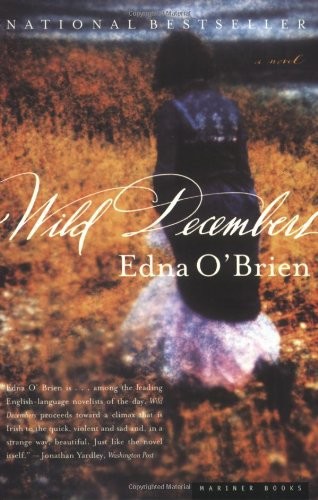

Wild Decembers

First Mariner Books edition 2001

Copyright © 1999 by Edna O’Brien

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

O’Brien, Edna.

Wild Decembers/Edna O’Brien,

p. cm.

ISBN

0-618-04567-8

ISBN

0-618-12691-0 (pbk.)

ISBN

978-0-6181-2691-0

1. Brothers and sisters—Ireland—Fiction. 2. Landowners—Ireland—Fiction. 3. Farm life—Ireland—Fiction.

I. Title.

PR

6065.

B

7

W

55 2000

823'.914—dc21 99-056110

e

ISBN

978-0-547-63064-9

v2.0314

. . . fifteen wild Decembers

From those brown hills have melted into spring—

Faithful indeed is the spirit that remembers. . .

Prologue—Emily Brontë

C

LOONTHA IT IS CALLED

—a locality within the bending of an arm. A few scattered houses, the old fort, lime-dank and jabbery and from the great whooshing belly of the lake between grassland and callow land a road, sluicing the little fortresses of ash and elder, a crooked road to the mouth of the mountain. Fields that mean more than fields, more than life and more than death too. In the summer months calves going suck suck suck, blue dribble threading from their black lips, their white faces stark as clowns. Hawthorn and whitethorn, boundaries of dreaming pink. Byroad and bog road. The bronze gold grasses in a tacit but unremitting sway. Listen. Shiver of wild grass and cluck of wild fowl. Quickening.

Fathoms deep the frail and rusted shards, the relics of battles of the long ago, and in the basins of limestone, quiet in death, the bone babes and the bone mothers, the fathers too. The sires. The buttee men and the long-legged men who hacked and hacked and into the torn breathing soil planted a first potato crop, the diced tubers that would be the bread of life until the fungus came.

According to the annals it happened on Our Lady’s Eve. The blight came in the night and wandered over the fields, so that by morning the upright stalks were black ribbons of rot. Slow death for man and beast. A putrid pall over the landscape, hungry marching people meek and mindless, believing it had not struck elsewhere. Except that it had. Death at every turn. The dead faces yellow as parchment, the lips a liquorice black from having gorged on the sweet poisonous stuff, the apples of death.

They say the enemy came in the night, but the enemy can come at any hour, be it dawn or twilight, because the enemy is always there and these people know it, locked in a tribal hunger that bubbles in the blood and hides out on the mountain, an old carcass waiting to rise again, waiting to roar again, to pit neighbour against neighbour and dog against dog in the crazed and phantom lust for a lip of land. Fields that mean more than fields, fields that translate into nuptials into blood; fields lost, regained, and lost again in that fickle and fractured sequence of things; the sons of Oisin, the sons of Conn and Connor, the sons of Abraham, the sons of Seth, the sons of Ruth, the sons of Delilah, the warring sons of warring sons cursed with that same irresistible thrall of madness which is the designate of living man, as though he had to walk back through time and place, back to the voiding emptiness to repossess ground gone for ever.

H

ERALDIC AND UNFLAGGING

it chugged up the mountain road, the sound, a new sound jarring in on the profoundly pensive landscape. A new sound and a new machine, its squat front the colour of baked brick, the ridges of the big wheels scummed in muck, wet muck and dry muck, leaving their maggoty trails.

It was the first tractor on the mountain and its arrival would be remembered and relayed; the day, the hour of evening, and the way crows circled above it, blackening the sky, fringed, soundless, auguring. There were birds always; crows, magpies, thrushes, skylarks, but rarely like that, so many and so massed. It was early autumn, one of those still autumn days, several fields emptied of hay, the stubble a sullied gold, hips and haws on the briars and a wild dog rose which because of its purple hue had been named after the blood of Christ—

Sangria Jesu.

At the top of the hill it slowed down, then swerved into a farmyard, stopping short of the cobbles and coming to rest on a grassy incline under a hawthorn tree. Bugler, the driver, ensconced inside his glass booth, waved to Breege, the young woman who, taken so by surprise, raised the tin can which she was holding in a kind of awkward salute. To her, the machine with smoke coming out of the metal chimney was like a picture of the Wild West. Already their yard was in a great commotion, their dog Goldie yelping, not knowing which part to bite first, hens and ducks converging on it, startled and curious, and coming from an outhouse her brother, Joseph, with a knife in his hand, giving him a rakish look.

“I’m stuck,” Bugler said, smiling. He could have been driving it for years so assured did he seem up there, his power and prowess seeming to precede him as he stepped down and lifted his soft felt hat courteously. Might he leave it for a day or two until he got the hang of the gears. He pointed to the manual that was on the dashboard, a thin booklet, tattered and with some pages folded where a previous owner had obviously consulted it often.

“Oh, no bother . . . No bother,” Joseph said, overcordial. The two men stood in such extreme contrast to one another, Joseph in old clothes like a scarecrow and Bugler in a scarlet shirt, leather gaiters over his trousers, and a belt with studs that looked lethal. He was recently home, having inherited a farm from an uncle, and the rumour spread that he was loaded with money and intended to reclaim much of his marshland. Because of having worked on a sheep station he had been nicknamed the Shepherd. A loner, he had not gone into a single house and had not invited anyone to his. The Crock, the craftiest of all the neighbours, who went from house to house every night, gleaning and passing on bits of gossip, had indeed hobbled up there, but was not let past the tumbling-down front porch. He was proud to report that it was no better than a campsite, and in sarcasm, he referred to it as the Congo. Bugler was a dark horse. When he went to a dance it was always forty or fifty miles away, but the Crock had reason to know that women threw themselves at him, and now he was in their yard, the sun causing glints of red in his black beard and sideburns. It was Breege’s first sensing of him. Up to then he had been a tall fleeting figure, apparition-like, so eager to master his surroundings that he rarely used a gate or a stile, simply leapt over them. Her brother and him had had words over cattle that broke out. The families, though distantly related, had feuds that went back hundreds of years and by now had hardened into a dour sullenness. The wrong Joseph most liked to relate was of a Bugler ancestor, a Henry, trying to grab a corner of a field which abutted onto theirs and their uncle Paddy impaling him on a road and putting a gun to his head. The upshot was that Paddy, like any common convict, had to emigrate to Australia, where he excelled himself as a boxer, got the red belts. Other feuds involved women, young wives from different provinces who could not agree and who screamed at each other like warring tinkers. Yet now both men were affable, that overaffability that seeks to hide any embarrassment. Joseph was the talkative one, expressing disbelief and wonder as each and every feature of the tractor was explained to him, the lever, the gears, the power shaft which, as Bugler said, could take the pants off a man or, worse, even an arm or a leg; then joyous whistles as Bugler recited its many uses—ploughing, rotating, foddering, making silage, and of course getting from A to B.

“It’s some yoke,” Joseph said, patting the side wing.

“If you ask me, she’s a he,” Bugler said, recalling the dangers, men in tractors to which they were unaccustomed having to be pulled out of bogholes in the dead of night, and a farmer in the Midlands driving over a travelling woman thinking he had caught a bough. Her tribespeople kept coming day after day strewing elder branches in wild lament.

They moved then to farming matters, each enquiring how many cattle the other had, although they knew well, and swapped opinions about the big new marts, the beef barons in their brown overalls and jobbers’ boots.

“How times have changed,” Joseph said overdramatically, and went on to quote from an article he had recently read, outlining the scientific way to breed pigs. The boar had to be kept well away from the sow so as to avoid small litters, but, nevertheless, had to be adjacent to her for the sake of smell, which of course was not the same as touch.

“Not a patch on touch . . . Nothing to beat touch,” one said, and the other confirmed it.

“Would you like a go on it?” Bugler said then to each of them.

“I’ll pass,” Joseph said, but added that Breege would. She shrunk back from them, looked at the machine, and then climbed up on it because all she wanted was to have got up and down again and vanish. Through the back of her thin blouse one hook of her brassiere was broken and Bugler would see that. A red colour ran up and down her cheeks as if pigment were being poured on them. It was like being up on a throne, with the fields and the low walls very insignificant, and she felt foolish.

“You’re okay . . . You’re okay . . . It won’t run away with you,” Bugler said softly, and leaned in over her. Their breaths almost merged. She thought how different he seemed now, how conciliatory, how much less abrupt and commanding. His eyes, the colour of dark treacle, were as deep as lakes, brown eyes, wounded-looking, as if a safety pin had been dragged over them in infancy. He saw her agitation, saw that she was uneasy, and to save the moment he told her brother that the bloke he bought the tractor from was a right oddball.

“How come?” Joseph said.

“He said that if I couldn’t start it, I was to find a child, get the child to put its foot on the clutch, but tell it to be ready to jump the moment the engine started.”

“You won’t find a child around here,” Joseph said, and in the silence they looked as if they were expecting something to answer back. Nothing did. It was as if they were each suspended and staring out at the fields, brown and khaki, and nondescript in the gathering dusk; fields over which many had passed, soldiers, pilgrims, journeymen, children too; fields on which their lives would leave certain traces followed by some dismay, then forgetfulness.

“You’ll come in for the tea,” Joseph said to lighten things.

“I won’t . . . I have jobs to do,” Bugler said, and turning to Breege, thinking that in some way he owed her an apology, he said, “If ever you want supplies brought from the town, you know who to ask.”