Wild Child: Girlhoods in the Counterculture (8 page)

Read Wild Child: Girlhoods in the Counterculture Online

Authors: Chelsea Cain

Tags: #Literary Collections, #Social History - 1960-1970, #Social Science, #1960-1970, #Hippies - United States, #United States - History - 1961-1969, #Girls, #Hippies, #General, #United States, #American, #Literary Criticism, #Girls - United States - History - 20th Century, #Social History, #Essays, #Fiction, #Girls - United States, #20th Century, #Biography, #History

Rain Grimes

Fear of a Bagged Lunch

I

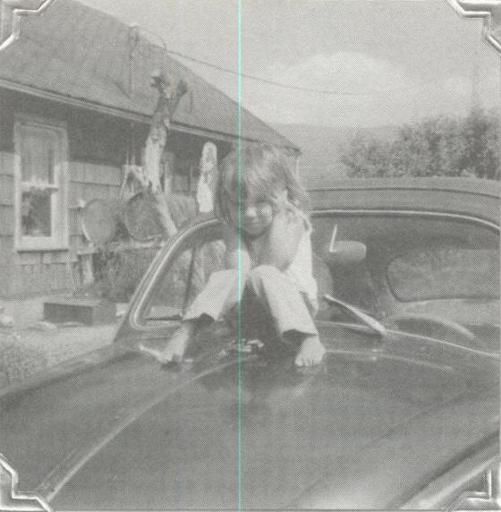

was born on the kitchen table. A midwife and my dad comprised the entire birthing team. My pacifist, Joni-Mitchell-singing, vegetarian-to-the-core, ‘who needs shampoo?’ parents did not even briefly consider the sterile experience of a hospital birth. When I finally let go of the embarrassment of that beginning enough to admit it to people, the story always elicited the same response: a wrinkle of the nose and the inevitable question ‘And you still ate on the table?’ It was a glorious moment for my parents, that Octo-.ber day in 1972, when they gave birth to their very own flower child. That kitchen table stood in a tiny cabin with no bathroom in rural Pennsylvania. My parents were both twenty-five and growing most of their own food, raising goats and making their own dairy products. I slept with my parents until I was five, drank goat’s milk and peed in an outhouse, blissfully unaware that the rest of the country didn’t live that way. Every photo of me shows a naked girl-child, sometimes with diaper, sometimes without, smudged with dirt and smiling like crazy. There are photos of me naked in tire swings, naked and spread-eagle in old stuffed chairs, naked and sitting on the dirty floor of our little house. One baby photo in particular was so embarrassing later that I went to great pains to hide it from my friends: I’m sitting on a pile of hay, one of my ears pierced, my smiling face exceptionally dirty, my hair a victim to home haircuts, and my cloth diaper so full it’s falling off my body. No pink velvet dresses and K-Mart balloon backdrops for my family.

When I was a year and a half, my parents loaded everything we owned, which wasn’t much, into a green 1952 Chevy truck and moved across the country to Washington State. My dad had built a miniature house on the back of the truck, and into this they packed our meager possessions, our two dogs and our goat Polly. (After a great deal of arguing my dad finally convinced my mom that there wasn’t room for her beloved chickens.) This picking up’ and moving across the country was a trend that was to continue throughout my young girlhood—a family tradition, of sorts.

Moving is easy when you own almost nothing, and even easier if the things you own are so battered that they become impervious to damage. Everything we possessed had been made by one of my parents or bought secondhand from Goodwill. When I wanted something we couldn’t afford (which was most of the time), my parents would do their best to build or sew it. I lusted after pinstriped jeans in third grade, and my mom valiantly sewed me stiff, ill-fitting pink denim jeans (which proceeded to fall off during a ferocious game of Red Rover). The year that Care Bears were in vogue, my brother and I received the homemade version. My mom was at a loss, luckily, when Cabbage Patch dolls hit the scene. My brother and I wanted bunk beds, and my dad promptly built them. My first bike was a hot pink number with a banana boat seat purchased at the local flea market. We got our first TV from

a

junk shop when I was twelve. It took me a long time to figure out that we were one step removed from the ‘normal’ consumer chain—and that it was both a financial necessity and a conscious ideological choice for my parents.

We lived my parents’ hippie dream in various New Age communities in Washington’s Skagit Valley and, later, in Sedona, Arizona. When I was six, we traveled across the country again, this time to Ithaca, New York, in a red Dodge van. Yet again my dad had masterminded his version of a hippie U-Haul camper and built a wooden sleeping platform in the back of the van. We spent our nights snuggled together on the platform under our one goose-down sleeping bag, looking at the stars out the van window and reading

The Chronicles ofNarnia

over and over again.

Life progressed in a similar fashion—traveling cross-country, sleeping with my parents, being naked much of the time. In Ithaca we lived in another cabin in the woods with no running water. I played in the creek, dodged the mice in our cabin, and passed countless hours melting crayons onto our wood stove. When I entered school in Ithaca, I went to an ‘alternative’ one called Hickory Hollow three bus rides away from our home. My parents subscribed to a theory of education that did not involve being forced to learn things that I wasn’t ‘ready’ to learn—an interesting, if at times impractical, concept. When I expressed my aversion to math to my first-grade teacher, she replied that I didn’t have to do my math homework if I didn’t want to—instead, why didn’t I go play in the corner in the fake tepee? Years later my seventh-grade teacher would wonder why I still didn’t know my multiplication tables.

Being a hippie kid always marked me as different. My family’s food choices were no exception. I was on the bus to Hickory Hollow with the kids from the local high school when it happened: my first public embarrassment over hippie food. My lunch box collapsed and out exploded oh-horrible-hippie-world-nonfat-plain-organic-goat’s-milk yogurt, covering the aisle of the bus, splashing onto the seats and me. And as I stood there, in my puffy green Goodwill coat and holey tights and little patchwork skirt, yogurt all over my shoes, the faces of horrified high schoolers gaped at me like I was an exotic bug. Perhaps other kids didn’t get yogurt in their lunch boxes—and if they did, it came in neat little plastic containers with cute foil lids and fruit on the bottom. This is the first time I can recall being conscious of my differences from other kids—and the moment when the protective bubble surrounding my idealized hippie kid existence first burst. I had been living in a sort of Utopian reality, with total, guileless freedom from worry about what other people thought of me. I realized in that moment that mine was not to be a mainstream existence.

My isolation blossomed to epic proportions when we moved to Beantown, Wisconsin. My parents had two folk musician friends there—and they wanted to start a band. We drove into Beantown in 1979 in a rusty blue Datsun wagon with, yes, duct tape holding on one of the fenders. We parked it in front of our friends’ house and camped out with them for some time. It seemed like months to my seven-year-old mind, and perhaps it was. However long, it was enough to bring the Beantown police to the door of the house, asking about the strange, vagrant car parked on the street. That visit from the police is cemented in my memory as my family’s initiation into our brand new identity as the town freaks. Did ‘normal’ people have the police coming to their door because their car looked so dilapidated? Somehow, I didn’t think so.

The vortex of the small-town Midwest sucked us in and held us captive for thirteen long years. There in the vortex, all the things about us that hadn’t seemed that strange before took on a whole new meaning. We were a complete anomaly to the residents of this tiny town. The people of Beantown must have been vaguely aware that the hippie culture existed, but it rarely, if ever, infiltrated their stable community. Other than my parents’ band mates, we stood alone on an island of hippie weirdness, or at least so it seemed to me at that young age when every difference is magnified. We were almost the only vegetarians in town. My parents were folk musicians, a virtually unheard of and severely misunderstood profession. My mom still made most of our clothes, and a wood stove was still our only source of heat. My mom wore colorful ethnic fabrics and knee-high leather boots instead of polyester pantsuits and flats. My dad bought all his clothes at the local Salvation Army, including the series of corduroy and leather vests that he remained strangely attached to even into the mid-eighties, much to my dismay. My parents weren’t Christians—they were pagans, and our ‘bible’ was a combination of the

l-Ching

, Tarot cards and the channelings of Seth. We drove a succession of rusty cars that always looked as if they couldn’t make it another mile, including one of our more embarrassing vehicles, a 1965 red Plymouth Valiant. The Valiant would swing into the school parking lot to pick me up after school, looking grossly out of place next to the Ford Escorts and minivans. When viewed through the lens of mainstream culture, our hippie ways were incomprehensible. Obscure lifestyles, or any sort of difference, can seem threatening in a small town—and we were misjudged accordingly. People saw my parents and immediately assumed (incorrectly) that they did drugs. I was taunted in eighth grade, asked if my parents had seen all of the Cheech and Chong movies. There was a vaguely dangerous mystique surrounding our difference.

Being different inside our home was easier to bear than the more public differences—no one could see my dad meditating or my mom playing the dulcimer. Food continued to be the most public declaration of my family’s strangeness. In my school they segregated the cold lunch kids from the hot lunch kids—and no, my mom did not allow me to eat any of the preservative-laden, non-organic foods full of processed meats and refined sugar served in my school cafeteria. I was, of course, a cold lunch kid. Which meant that I had to sit at a table in the lunch room that for some reason was perpendicular to all the rows of hot lunch tables. We, the few cold lunch kids, spent the whole hour providing an amusing visual distraction for the hot lunch kids. Our bagged lunches were of great interest to the hot lunchers—something to look at while they slurped down hot dogs and mac-n-cheese and chocolate cake and jello and hamburgers and chop suey. And my lunch was the most interesting of all. The kids had seen Velveeta and white bread and Cheetos and Capri Sun juice boxes before, but they hadn’t been exposed to homemade wheat bread and blue corn chips and tofu and natural licorice. And so it happened again and again—the dreaded natural food incident. The pdinting finger, the gaping mouth and the inevitable comment: ‘What

is

that?’ How could I explain blue corn chips to kids raised on white bread? I tried to be strong—I tried to stand up for my family’s organic choices, and I tried to tell them that the chips tasted good. But they were wasted words—because to them all that mattered was that the food looked different, which made it weird, which made

me

weird.

My repeated public embarrassments due to the contents of my lunch bag bred a deep resentment inside me about my family’s food choices. I begged my dad to buy hot dogs. Secretly plotting which sugar cereals I could get my hands on and dreaming of Os-, car Meyer bologna sandwiches on white bread with that nice bright yellow mustard, I revolted. My tolerance for their food choices hit its limit with tempeh. My mom grew tempeh in their bedroom. It smelled bad and looked worse. Their bedroom floor was covered with pans of white molding cakes, which my mom would bring downstairs, slice into neat squares, fry and serve for dinner. I would not eat tempeh.

My friends went to college and became vegetarians. I went to college and became a meat eater. After nineteen years of being force-fed tofu and beans and rice, vegetarianism did not hold an enigmatic appeal for me. Early in my freshman year a large group of my newly turned vegetarian friends discovered, to their immense joy, a restaurant that served tofu dogs. This was like the Second Coming for them. They came to my room in an excited bunch, inviting me to join them to ‘go out for tofu dogs.’ I declined. The natural foods craze held no sense of independence or contained rebellion for me. I felt more insurgent satisfaction from eating a hamburger or a slice of chocolate cake. So even now, as an adult who enjoys eating healthy foods and is surrounded by a community that sanctions rather than punishes this choice, I am still guilty of occasional secret trips to the drive-through lane of fast-food restaurants. I lust after processed sugar, red meat, full-fat dairy. It is the legacy of growing up vegetarian and sugar free, the curse of the hippie kid turned adult.

By the time I was a teenager, I had already lived as a nonconformist and, in some ways, that left me no direction to go but toward conformity. My parents had already fought many battles for me. I was so free to become who I wanted to be that I just wanted to be like everyone else. In high school, my friends rebelled against authority by stealing their parents’ cigarettes, skipping class and getting stoned at lunch. I curled my bangs and became a cheerleader and class president. My classmates did Tarot cards and listened to Pink Floyd. I did my homework religiously and organized the school prom. Thankfully, my parents were patient enough to let this wild stage run its course, as I pranced through my teen years in disguise—my bangs curled high and immobilized with hair spray, my lips glimmering with shell-pink lipstick, my jeans rolled tight to my leg, my Keds whiter than white. They may have secretly lamented my embrace of the trappings of mainstream teenage life—but they never said a word.

My rebellious phase is long past; normalcy is no longer an icon. I left the towering bangs by the wayside. More important, however, is that everything that once felt shameful now seems interesting; I actually enjoy the looks of incredulity from people who did not grow up as I did when I tell my childhood story. I’m no longer embarrassed to describe the setting of my birth—or to admit that my parents weren’t married until I was seven. I beg my mom to sew me clothes, having long forgotten the trauma of the pink jeans. I humbly ask her how best to cook tofu, and don’t mind that people know my dad still meditates on a nightly basis. Our family mantra, ‘You create your own reality,’ our version of the Lord’s Prayer, has found its way into my daily life. I try to balance my parents’ hippie values with my own brand of nineties realism and a healthy dose of ex-hippie-kid skepticism. I’ve stopped view-ipg the world through a lens that magnifies difference and makes it undesirable. And I’ve finally forgiven my parents for all the rusty cars and tofu sandwiches, for the homemade Care Bears and home haircuts. They knew what they were doing.