Why We Love Serial Killers (28 page)

Read Why We Love Serial Killers Online

Authors: Scott Bonn

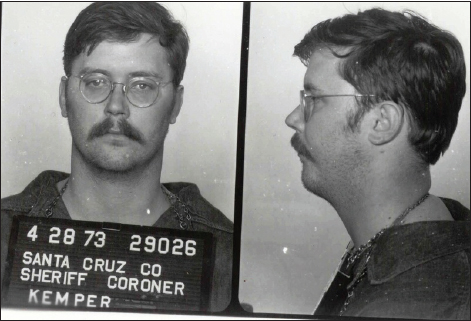

Ed Kemper’s mugshot following his arrest in April 1973.

Kemper finally realized his ultimate fantasy and killed his mother with a claw hammer and strangled her best friend on Good Friday 1973. After having sex with his mother’s decapitated head, Edmund Kemper casually telephoned the local law enforcement authorities to confess what he had done. The police initially refused to believe him, thinking that their friend “Big Eddie” was just pulling a prank on them. After several follow-up calls and the disclosure of information that only the “Co-ed Killer” would know, Kemper finally convinced the police that he was the man they sought. He was quickly arrested without incident and charged with eight murders in the first degree. Kemper was found guilty and given a life sentence because there was a stay on the death penalty in the US at the time of his conviction.

Given his homicidal obsession with his mother, one might wonder whether killing her exorcised the demons that had tormented Ed Kemper throughout his life and finally provided him with a twisted sense of closure. As it turns out, the answer to this question is simultaneously chilling and fascinating. Kemper was asked by a

Cosmopolitan

magazine reporter during a prison interview how he felt when he saw a pretty girl after killing his mother. He said, “One side of me says, I’d like to talk to her, date her. The other side says, I wonder how her head would look on a stick.”

The inglorious atrocity tale of Edmund Kemper demonstrates just how loathsome the actions of a real-life serial killer can be. Although the abuse he suffered during childhood was tragic and terrible, and while it offers some insights into his criminal pathology, Kemper’s odyssey of murder, dismemberment, and sexual perversion still defies comprehension. No hyperbole is required for his crimes to shock and horrify the public, yet the facts of Kemper’s murders are often misrepresented or exaggerated in their retelling by the entertainment media. There are numerous books, films, puzzles, poems, calendars, and games that hyperbolize his story of murder and mayhem. For example, he was portrayed as a demonic freak in a slash-and-gore book titled

The Lonely Head-Hunter: Ed Kemper

and has appeared as a supernatural

monster in comic books. There is an Ed Kemper gothic horror necklace and locket for sale on the Internet. The 2008 horror film

Kemper: The Co-ed Killer

is almost entirely devoid of facts. As a result of his inaccurate and sensationalized depiction in the entertainment media, Kemper has been transformed into a celebrity folk devil.

I contend that the grotesque and stylized depiction of Ed Kemper and his crimes have obscured the distinction between reality and fiction for the general public. That is, incessant media stereotyping has changed Ed Kemper from a human being into a serial killer caricature similar to “Freddy Krueger” in the

Nightmare on Elm Street

horror film franchise. I believe that Kemper and Krueger have become interchangeable in the minds of the public due to the inaccurate depiction of serial killers in the mass media. I also believe that it no longer matters to serial killer fans whether the media image is a real-life predator such as Kemper or a fictionalized one such as Krueger. They are equally scary and entertaining to the public. I argue that this stereotyping harms society because the blurring of reality and fiction causes confusion and desensitizes the public to the truth about real-life serial killers and their victims. If Ed Kemper becomes just another cartoonish entertainment commodity like Freddy Krueger, then the actual horrors he perpetrated and the lives he destroyed are forgotten. This is unfair to Kemper’s victims and only intensifies the tragedy and pain for their surviving family members. I explore these troubling notions in the chapters that follow.

Conclusion

In this chapter I introduced a sociological theory called social constructionism and a related concept known as moral panic, which together provide insights into the social construction of serial killers. I have argued that the concept of evil is socially defined and that influential parties such as law enforcement, politicians, the news media, and the public contribute to the distorted public identity of serial killers. I have argued that inflammatory stories known as atrocity tales also contribute to the social construction of serial killers. I presented the story of Ed Kemper, a real-life serial killer whose sensationalized tale of atrocity has transformed him into a celebrity monster on the popular culture landscape. We now turn to the evidence that supports the claims made in this chapter.

CHAPTER 10

THE MAKING OF CELEBRITY MONSTERS

In his book

Wayward Puritans: A Study in the Sociology of Deviance

, Kai Erikson wrote:

Investigators have studied the character of the deviant’s background, the content of his dreams, the shape of his skull, the substance of his thoughts—yet none of this information has enabled us to draw a clear line between the kind of person who commits deviant acts and the kind of person who does not.

106

This statement expresses the public’s curious desire or perhaps compulsion to understand the reasons that some people do very bad things. Because serial killers are among the most egregious of all criminal offenders, many of us want to understand why they do what they do. Their actions seem incomprehensible to us, which could explain why they are particularly fascinating for us to contemplate. The public’s curiosity about serial killers leads the news media to focus a tremendous amount of time and attention on them relative to other offenders. The intense media spotlight elevates them to the realm of criminal rock stars.

In the previous chapter, I introduced the moral panic concept to demonstrate how certain social agents such as the news media, law enforcement authorities, and the public are involved in the creation of larger-than-life criminal folk devils. I maintain that serial killers fit the folk devil classification due to an exaggeration by law enforcement and the news media to the threat they actually pose to society. In this chapter, I attempt to answer the central question of this book: What makes serial killers so interesting to so many people? In order to answer this question, I demonstrate how each of the key agents discussed in

chapter 9 contributes to the social construction of serial killers and their celebrity monster status. It is important to remember that many serial killers such as the Son of Sam, the Night Stalker (discussed in this chapter), and BTK, to name just a few, were active contributors to the construction of their own public images. Therefore, I include their voices as an essential part of my explanation of this phenomenon. Throughout this chapter, I use the actual words of homicide detectives, FBI criminal profilers, investigative journalists, academics, and notorious predators to provide insights into the social construction of celebrity serial killers and the public’s fascination with them.

How Key Social Agents Construct Serial Killers

The moral panic concept can help to explain how and why certain social agents such as politicians, law enforcers, and the news media sometimes exaggerate the threat posed to society by a particular individual or group to further their own agendas. As explained in the last chapter, law enforcers and elected politicians must work to justify their respective positions in the social hierarchy. These agents of the state are expected to detect, apprehend, and punish anyone who threatens the social order. In fact, law enforcers and elected politicians have a sworn duty and moral obligation to protect society from any internal or external threats that may appear. The police and elected officials are charged with enforcing the laws of the state, so it is important to their public images and careers to be perceived as fearless protectors of society. Therefore, law enforcement agencies frequently frame their crime fighting efforts in terms of good versus evil in such a way that they emerge as the force of good.

The Role of Law Enforcement Authorities

The normal routines of policing and the relative scarcity of serial homicide incidents both contribute to the reinforcement of serial killer stereotypes by law enforcement authorities. As explained in chapter 2, law enforcement professionals often circulate misinformation about serial homicide due to their reliance on anecdotal information rather than on scientifically documented patterns of serial killer behavior. Most law enforcement professionals, including detectives, prosecutors, and pathologists, have very limited exposure to serial killer cases. The

rarity of serial homicide means that even a veteran professional’s total experience may be limited to a single investigation. Therefore, he or she is likely to extrapolate the factors from that one experience to another serial murder investigation when such a case presents itself. As a result, certain stereotypes and misconceptions take root among law enforcement authorities regarding the nature of serial homicide and the characteristics of serial killers.

Ultimately, state managers, including law enforcement and politicians, define who and what is evil in society and those definitions, whether or not they are based on stereotypes, become the accepted reality for the majority of the population. When the police define a serial killer as evil or a monster they are exercising their power to construct reality according to their own specifications and needs. The earliest known use of the term “monster” in this context dates back to 1790 in London when law enforcement authorities sought a sexual deviant who committed a series of “nameless crimes, the possibility of whose existence no legislator has ever dreamed of.” The so-called monster stalked well-dressed women in the streets and slashed more than fifty of them over a two-year period. One hundred years later, also in London, the serial killer known as Jack the Ripper was declared to be a “monster” and a “maniac” by police authorities.

In contemporary society, the terms “evil” and “monster” are frequently used by law enforcement officials to explain serial killers in their public statements. For example, Richard Ramirez—the Satan-worshipping Night Stalker who claimed to have been inspired by Jack the Ripper and the infamous cannibal and killer, Jeffrey Dahmer—was persistently described as “evil” by the police. More recently, the unidentified predator known simply as the Long Island Serial Killer has been called a “cold-blooded monster” by his pursuers. In addition, the popular memoir of the late FBI profiler Robert Ressler is entitled

Whoever Fights Monsters

.

The definition of the word “monster” still retains its original implications of supernatural or non-human origins to one so defined. Similarly, the word “evil” strips the humanity from anyone unlucky enough to receive the designation. Significantly, when a law enforcement official uses terms such as monster or evil to describe a serial killer, he is characterizing the criminal as a larger-than-life super predator. By so doing, he is also presenting himself as a superhero with the ability to defeat the super villain. Stated differently, and borrowing from author Bram Stoker, the wanted criminal becomes Count Dracula and the

obsessed police pursuer becomes the vampire hunter, Dr. Abraham Van Helsing.

However, not all law enforcement authorities approve of the use of supernatural terminology to describe serial killers. Some find the practice to be counterproductive or even dangerous. For example, former FBI profiler Roy Hazelwood, a colleague of the late Robert Ressler, decries the practice of labeling serial killers using such terminology for reasons that are both logical and pragmatic. Hazelwood told me:

When I teach “profiling,” I tell my students that, when referring to sexual killers, they are not use the following terms in my class: “Pervert,” “weirdo,” “wacko,” “monster,” “sicko” . . . regardless of the type of crime(s) the serial killer has committed. My reasoning is that when they use those terms to describe the offender, they have begun the process of structuring a mindset as to the type of person they are looking for when in reality he may be a person studying to become a doctor (Craiglist Killer) or a lawyer (Ted Bundy) or a police officer (Gerard Schaefer).

So no, I don’t believe that “monster” is a descriptor that should be used because the lay person then applies his/her idea of what a “monster” looks or behaves like and consequently, when the offender is identified, the public is shocked at how “normal” he appears.

Hazelwood’s powerful observations explain how the police often construct a public identity for a serial killer that is nothing like the actual person. Truth be told, a serial killer is much more likely to come across as the mild-mannered Dennis Rader in person than as the socially constructed monster known as BTK. When law enforcement authorities describe a serial killer in one-dimensional and supernatural terms, they perpetuate a stereotype that harms society by distorting the true nature and extent of the threat represented by the criminal.