Why was the Partridge in the Pear Tree? (8 page)

Read Why was the Partridge in the Pear Tree? Online

Authors: Mark Lawson-Jones

The Twelfth Night.

Over the years, people have noticed that the pear tree might actually be the word

perdrix

, French for partridge and pronounced ‘per-dree’, which was simply copied down incorrectly when the oral version of the game was transcribed. The original line would have been: ‘A partridge, une perdrix.’. Whichever might be correct, Madamme Perdrix is almost certainly French, whether in a tree or not.

The game would have turned into a song sometime after the publication of

Mirth Without Mischief

in 1780, although Lady Gomme, (1853-1938) the prolific collector of folk tales and rhymes, described playing the game every twelfth night, before eating mince pies and the twelfth cake, a light dried fruit cake made with brandy and eggs.

Lady Gomme, in her

Dictionary of British Folk-Lore – Volume 1

(1894) points out that the festival of the twelve days, the ‘great midwinter feast of Yule’, was a very important one, and that ‘in this game may, perhaps, be discerned the relic of certain customs and ceremonies and the penalties or forfeits incurred by those who omitted religiously to carry them out’, she also adds that it was ‘a very general practice for work of all kinds to be put entirely aside before Christmas and not resumed until after Twelfth Day.’

The most common musical setting for this game that turned it into a song is a popular folk tune that changes time signature throughout the song. The Roud Folk Song Index, a database of over 300,000 references to 21,600 songs, named after its founder Steve Roud, Local Studies Librarian in the London Borough of Broydon, gives the tune an index number of sixty-eight. The earliest well-known version of the music was recorded by English Scholar James O’Halliwell in 1842, which he published in his book

The Nursery Rhymes of England

in 1846. The five gold rings pivotal bars first appeared in an arrangement by the English composer Frederick Austin, which he copyrighted in 1909. In the last 150 years many different versions of this song have come to light, this isn’t uncommon, as many of our favourite carols and songs are regularly set to different folk tunes.

So, we’ve found that the game, which turned into a Christmas song, is almost certainly French in origin, written long before the first discovered printing in 1780, and that the music is relatively recent.

The detective work doesn’t end there though. There are questions about whether it is a nonsense song for children or a rhyme of Christian instruction, perhaps dating to the sixteenth century, when hidden references were placed in songs and rhymes to teach the faith to youngsters. This was a time of great uncertainty and religious strife, with the Protestant Reformation and revolt throughout Europe and the separation of the Church of England from Rome. Perhaps this rhyme or song was part of the counter-reformation that ran from the beginning of the Council of Trent in (1545-1563) until the end of the Thirty Years War (1648), although Catholics were still prevented from practicing their faith openly until 1829.

‘The Twelve Days of Christmas’ as a catechism song would give each verse a religious significance.

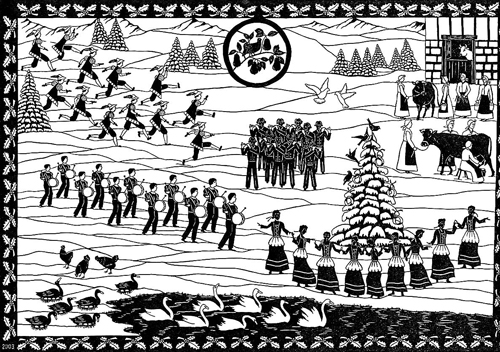

A depiction of the Twelve Days of Christmas.

Verse | Meaning |

One partridge in a pear tree | Jesus |

Two Turtle doves | The Old and New Testaments |

Three French Hens | Three theological virtues of faith, hope and love (charity) |

Four calling birds | The four Gospels; Matthew, Mark, Luke and John |

Five gold rings | The ‘Torah’ or ‘Pentateuch’ the first five books of the Old Testament (The Law of Moses) |

Six geese a-laying | The six days of Creation |

Seven swans a-swimming | The seven gifts of the Holy Spirit; wisdom, understanding, counsel, fortitude, knowledge, piety and fear of the Lord. |

Eight maids a-milking | The eight beatitudes. The Gospels according to Matthew or Luke differ slightly. Matthew’s Gospel lists them as; The poor in spirit, those who mourn, those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, those who are persecuted because of seeking righteousness, the meek, the merciful, the pure in heart and the peacemakers. |

Nine ladies dancing | The nine fruits of the Holy Spirit are listed in the letter of St Paul to the Galatians ‘But the fruit of the Spirit is love, joy, peace, longsuffering, gentleness, goodness, faith, meekness, temperance: against such there is no law.’ Galatians 5:22-3, The Bible – King James Version |

Ten lords a-leaping | The Ten Commandments; You shall have no other Gods, you shall not make idols, do not take the God’s name in vain, observe the Sabbath, honour your father and mother, do not kill, do not commit adultery, do not steal, do not bear false witness, do not covet your neighbours wife, do not covet your neighbours belongings. |

Eleven pipers piping | The eleven faithful Apostles; Peter, Andrew, James, John, Philip, Bartholomew, Matthew, Thomas, James (son of Alphaeus), Thaddeus, Simon the Zealot (ignoring Judas of course, who was supposed to have betrayed Christ). |

Twelve drummers drumming | The twelve points of the Apostles Creed; I believe in God the father, almighty, maker of heaven and earth, and in Jesus Christ his only Son our Lord, who was conceived by the Holy Ghost, born of the Virgin Mary, suffered under Pontius Pilate, was crucified, dead and buried, he descended into hell. The third day he rose again from the dead and ascended into heaven, and sitteth at the right hand of the God the Father Almighty, from thence He shall come to judge both the quick and the dead. I believe in the Holy Ghost; the Holy Catholick (sic) church; the Communion of Saints; the Forgiveness of sins; the Resurrection of the body, and the Life Everlasting.’ |

Many have questioned the historical accuracy of this religious origin of the song. Some have suggested it is merely an ‘urban myth’, although there is little ‘hard’ evidence available either way. Some Church historians affirm this account as accurate, whilst others point out discrepancies that could mean the song is merely a good catchy folk tune to words that provided entertainment on the long dark January nights many years ago.

We may never know for certain, but for those who have good memories and the ability to sing a folk song in a different meter and at some speed, this is a favourite.

The Holly and the Ivy

The holly and the ivy,

When they are both full grown

Of all the trees that are in the wood

The holly bears the crown.

The holly bears a blossom

As white as lily flower

And Mary bore sweet Jesus Christ

To be our sweet Saviour.

The holly bears a berry

As red as any blood,

And Mary bore sweet Jesus Christ

To do poor sinners good.

The holly bears a prickle

As sharp as any thorn,

And Mary bore sweet Jesus Christ

On Christmas Day in the morn.

The holly bears a bark

As bitter as any gall,

And Mary bore sweet Jesus Christ

For to redeem us all.

The holly and the ivy,

When they are both full grown

Of all the trees that are in the wood

The holly bears the crown.

Carols and hymns never stand alone as mere songs; they all have rich origins that tell a story down the centuries. Intermingled with the Christian imagery in many Christmas carols there is also mention made of evergreen plants and historical details that deserve investigation. To properly understand these symbols and their significance, we need to dig a little deeper, beyond what is commonly accepted about our hymns and carols.

Holly.

The carol ‘The Holly and the Ivy’ is no exception. In this particular carol, which is undoubtedly religious in content, the holly’s features symbolize Jesus and his suffering. The holly produces a white blossom representing his purity. Its scarlet clusters of berries reflect his blood. The holly also has a sharp prickle; this almost certainly symbolizes the crown of thorns worn by Jesus at the time of his death. The question remains however, why is this symbolism used at all? It doesn’t belong to Biblical text or early Christian tradition.

In distant history, we know that the Romans would send boughs of holly and ivy to their friends to celebrate the winter festival of Saturnalia, to honour the God Saturnus, the God of agriculture.

Even though the Romans left Britain in

AD

410, the tradition must have been retained or adopted as a Christmas celebration because in

AD

596, when St Austin and his disciples baptized 10,000 Anglo-Saxons on Christmas Day, we are told that churches and houses were bedecked for two weeks with holly and ivy to celebrate the occasion. This may well have secured the link between holly and ivy and the mid-winter celebrations.

There is also a link to pagan historical practice, where in the winter when nothing flowers, evergreen plants such as holly, ivy, fir and pine were considered to be a sign of new life, holding magical qualities to ward off evil, ghosts and lightning.

A Harleian manuscript dating back to

AD

1451 includes a story of a contest between holly and ivy for the best place in the house. ‘Nay, Ivy, Nay’ tells us that the holly was finally victorious because the black berries of the ivy were no match for the beauty of the red berries on the holly wreath. This probably reflects the ongoing pagan relationship with holly and ivy as signs of good luck and the anticipation of new life in spring, even in the depths of winter.