Why the West Rules--For Now (71 page)

Read Why the West Rules--For Now Online

Authors: Ian Morris

Tags: #History, #Modern, #General, #Business & Economics, #International, #Economics

In China the civil service became a particular flashpoint. The ranks of the gentry swelled but numbers of administrative positions did not,

and as the thorny gates of learning narrowed, the rich found ways to make wealth matter more than scholarship. One county official complained that “

poor scholars

who hoped to get a place [at the examinations] were dismissed by the officials as though they were famine refugees.”

Even for kings, at the very top of the pile, these were tense times. In theory, rising population was good for rulers—more people to tax, more soldiers to enlist—but in practice things were not so simple. Pressed into a corner, hungry peasants might rebel rather than pay taxes, and fractious, feuding nobles often agreed with them. (Failed Chinese civil service candidates developed a particular habit of resurfacing as rebels.)

The problem was as old as kingship itself, and most sixteenth-century kings chose old solutions: centralization and expansion. Japan was perhaps the extreme case. Here political authority had collapsed altogether in the fifteenth century, with villages, Buddhist temples, and even individual city blocks setting up their own governments and hiring toughs to protect them or rob their neighbors.

*

In the sixteenth century population growth set off ferocious competition for resources, and from lots of little lords there gradually emerged a few big ones. The first Portuguese guns reached Japan in 1543 (a generation ahead of the Portuguese themselves) and by the 1560s Japanese craftsmen were making outstanding muskets of their own, just in time to help already-big lords who could afford to arm their followers get bigger still. In 1582 a single chief, Toyotomi Hideyoshi, made himself shogun over virtually the whole archipelago.

Hideyoshi talked his quarrelsome countrymen into handing over their weapons, promising to melt them down into nails and bolts for the world’s biggest statue of the Buddha, twice as tall as the Statue of Liberty. This would “

benefit the people

not only in this life but in the life hereafter,” he explained. (A Christian missionary was unimpressed; Hideyoshi was “

crafty and cunning

beyond belief,” he reported, “depriving the people of their arms under pretext of devotion to Religion.”)

Whatever Hideyoshi’s spiritual intent may have been, disarming the people was certainly a huge step toward centralizing the state, greatly easing the task of counting heads, measuring land, and assigning tax and military obligations. By 1587, according to a letter he sent to his wife, Hideyoshi saw expansion as the solution to all his problems and decided to conquer China. Five years later his army—perhaps a quarter-million strong, armed with the latest muskets—landed in Korea and swept all before it.

He faced a Chinese Empire deeply divided over the merits of expansion. Some of the Ming emperors, like Hideyoshi in Japan, pushed to overhaul their empire’s rickety finances and expand. They ordered up new censuses, tried to work out who owed taxes on what, and converted complicated labor dues and grain contributions into simple silver payments. Civil servants, however, overwhelmingly shunned all this sound and fury. Centuries of tradition, they pointed out, showed that ideal rulers sat quietly (and inexpensively) at the center, leading by moral example. They did not wage war and certainly did not squeeze money out of the landed gentry, the very families that the bureaucrats themselves came from. Censuses and tax registers, Hideyoshi’s pride and joy, could safely be ignored. So what if one prefecture in the Yangzi Valley reported exactly the same number of residents in 1492 as it had done eighty years earlier? The dynasty, scholars insisted, would last ten thousand years whether it counted the people or not.

Activist emperors floundered in a bureaucratic quagmire. Sometimes the results were comical, as when Emperor Zhengde insisted on leading an army against the Mongols in 1517 only for the official in charge of the Great Wall to refuse to open the gates to let him through because emperors belonged in Beijing. Sometimes things were less amusing, as when Zhengde had his senior administrators whipped for stubbornness, killing several in the process.

Few emperors had Zhengde’s energy, and rather than take on the bureaucratic and landed interests, most let the tax rolls decay. Short of money, they stopped paying the army (in 1569 the vice-minister for war confessed that he could find only a quarter of the troops on his books). Bribing the Mongols was cheaper than fighting them.

Emperors also stopped paying the navy, even though it was supposed to be suppressing the enormous black market that had sprung up since Hongwu had banned private maritime trade back in the fourteenth

century. Chinese, Japanese, and Portuguese smugglers ran lucrative operations up and down the coast, buying the latest muskets, turning piratical, and easily outgunning the underfunded coastguards who intercepted them. Not that the coastguards really tried; kickbacks from smugglers were among their major perks.

China’s coast increasingly resembled something out of TV cop shows such as

The Wire

, with dirty money blurring distinctions among violent criminals, local worthies, and shady politicians. One upright but naïve governor learned this the hard way when he actually followed the rules, executing a gang of smugglers even though one of them was a judge’s uncle. Strings were pulled. The governor was fired and committed suicide when the emperor issued a warrant for his arrest.

The government effectively lost control of the coast in the 1550s. Smugglers turned into pirate kings, controlling twenty cities and even threatening to loot the royal tombs at Nanjing. In the end it took a whole team of officials, politically savvy as well as incorruptible, to defeat them. With a covert force (known as “Qi’s Army” after Qi Jiguang, the most famous of these untouchables) of three thousand musketeers, the reformers fought a shadow war, sometimes with official backing, sometimes not, funded by a prefect of Yangzhou who channeled money to them under the table by squeezing back taxes out of the local elite. Qi’s Army showed that when the will was there the empire could still crush challengers, and its success inspired a (brief) era of reform. Transferred to the north, Qi revolutionized the Great Wall’s defenses, building stone towers,

*

filling them with trained musketeers, and mounting cannons on carts like the wagon forts that Hungarians had used against the Ottomans a century before.

In the 1570s Grand Secretary Zhang Zhuzheng, arguably the ablest administrator in Chinese history, updated the tax code, collected arrears, and modernized the army. He promoted bright young men such as Qi and personally oversaw the young emperor Wanli’s education. The treasury refilled and the army revived, but when Zhang died in 1582 the bureaucrats struck back. Zhang was posthumously disgraced

and his acolytes fired. The worthy Qi died alone and penniless, abandoned even by his wife.

Emperor Wanli, frustrated at every turn now that his great minister was gone, lost all patience and in 1589 went on strike. Withdrawing into a world of indulgence, he squandered a fortune on clothes and got so fat that he needed help standing up. For twenty-five years he refused to attend imperial audiences, leaving ministers and ambassadors kowtowing to an empty throne. Nothing got done. No officials were hired or promoted. By 1612 half the posts in the empire were vacant and the law courts had backlogs years long.

No wonder Hideyoshi expected an easy victory in 1592. But whether because Hideyoshi made mistakes, because of Korean naval innovations, or because the Chinese army (especially the artillery Qi had established) performed surprisingly well, the Japanese attack bogged down. Some historians think Hideyoshi would still have conquered China had he not died in 1598, but as it was, Hideyoshi’s generals immediately rethought expansion. Abandoning Korea, they rushed home to get on with the serious business of fighting one another, and Wanli and his bureaucrats went back to their own serious business of doing not very much at all.

After 1600, the great powers of the Eastern core tacitly agreed that the bureaucrats were right: centralization and expansion were not the answers to their problems. The steppe frontier remained a challenge for China, and European pirates/traders still posed problems in Southeast Asia, but Japan faced so few threats that—alone in the history of the world—it actually stopped using firearms altogether and its skilled gunsmiths went back to making swords (not, alas, plowshares). In the West, however, no one had that luxury.

THE CROWN IMPERIAL

In a way, the Western and Eastern cores looked rather similar in the sixteenth century. In each, a great empire dominated the traditional center (Ming China in the Yellow and Yangzi river valleys in the East, Ottoman Turkey in the eastern Mediterranean in the West) while smaller commercially active states flourished around its edges (in Japan and Southeast Asia in the East, in western Europe in the West). But

there the similarities ended. In contrast to the squabbles in Ming China, neither the Ottoman sultans nor their bureaucrats ever doubted that expansion was the answer to their problems. Constantinople had been reduced to fifty thousand people after the Ottoman sack in 1453 but rebounded as it once more became the capital of a great empire. Four hundred thousand urbanites lived there by 1600, and—like Rome so many centuries before—they needed the fruits of the whole Mediterranean to feed themselves. And like ancient Rome’s senators, Turkey’s sultans resolved that conquest was the best way to guarantee all these dinners.

The sultans carried on a complex dance, keeping one foot in the Western core and one in the steppes. This was the secret of their success. In 1527 Sultan Suleiman reckoned that his army boasted 75,000 cavalry, mostly aristocratic archers of traditional nomad type, and 28,000 Janissaries, Christian slaves trained as musketeers and backed by artillery. To keep the horsemen happy, sultans parceled out conquered lands as fiefs; to keep the Janissaries content—that is, paid in full and on time—they drew up land surveys that would have impressed Hideyoshi, managing cash flows to the last coin.

All this took good management, and a steadily expanding bureaucracy drew in the empire’s best and brightest while the sultans adroitly played competing interest groups against one another. In the fifteenth century they often favored the Janissaries, centralizing government and patronizing cosmopolitan culture; in the sixteenth they leaned toward the aristocracy, devolving power and encouraging Islam. Even more important than these nimble accommodations, though, was plunder, which fueled everything. The Ottomans needed war, and usually won.

Their toughest tests came on their eastern front. For years they had confronted a low-grade insurgency in Anatolia (

Figure 9.4

), where Red-Head

*

Shiite militants denounced them as corrupt Sunni despots, but this ulcer turned septic when the Persian shah declared himself the descendant of ‘Ali in 1501. The Shiite challenge gave focus to the hungry, dispossessed, and downtrodden of the empire, whose violent rage shocked even hard-bitten soldiers: “

They destroyed everything

—men,

women, and children,” one sergeant recorded of the rebels. “They even destroyed cats and chickens.” The Turkish sultan pressured his religious scholars into declaring the Shiites heretical, and jihads barely let up across the sixteenth century.

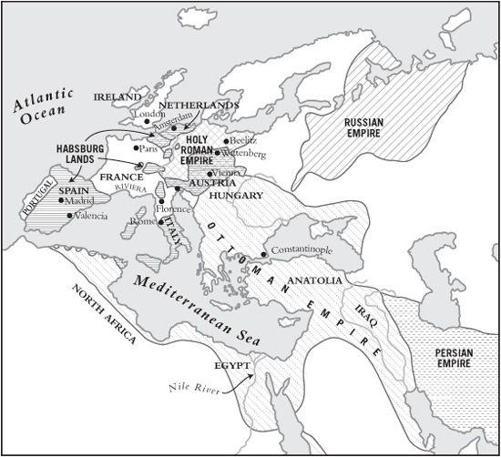

Figure 9.4. The Western empires: the Habsburg, Holy Roman, Ottoman, and Russian empires around 1550

Superior firearms gave the Ottomans the edge, and though they never completely defeated Persia they were able to fight it to a standstill and then swing southwest to take the biggest prize of all, Egypt, in 1517. For the first time since the Arab conquests nearly nine centuries earlier, hungry Constantinopolitans now had guaranteed access to the Nile breadbasket.

But like every expansionist power since the Assyrians, the Ottomans found that winning one war just set off another. To reinstate the Egypt-Constantinople grain trade they had to build a fleet to protect their ships, but their victories over the Mediterranean’s ferocious pirates

(Muslim as well as Christian) only drew the fleet farther west. By the 1560s Turkey controlled the whole North African coast and was fighting western European navies. Turkish armies also pushed deep into Europe, overwhelming the fierce Hungarians in 1526 and killing their king and much of their aristocracy.

In 1529 Sultan Suleiman was camped outside Vienna. He was unable to take the city, but the siege filled Christians with terror that the Ottomans would soon swallow all Europe. “

It makes me shudder

to think what the results [of a major war] must be,” an ambassador to Constantinople wrote home.

On their side is the vast wealth of their empire, unimpaired resources, experience and practice in arms, a veteran soldiery, an uninterrupted series of victories … On ours are found an empty treasury, luxurious habits, exhausted resources, broken spirits … and, worst of all, the enemy are accustomed to victory, we, to defeat. Can we doubt what the result must be?