Why the West Rules--For Now (59 page)

Read Why the West Rules--For Now Online

Authors: Ian Morris

Tags: #History, #Modern, #General, #Business & Economics, #International, #Economics

By then the Eastern and Western cores had each fragmented into ten-plus states, yet despite the similarities between the breakdowns in the two cores, Eastern social development continued to rise faster than Western. The explanation once again seems to be that it was not emperors and intellectuals who made history but millions of lazy, greedy, and frightened people looking for easier, more profitable, and safer ways to do things. Regardless of the mayhem that rulers inflicted on them, ordinary people muddled along, making the best of things; and because the geographical realities within which Easterners and Westerners were muddling differed strongly, the political crises in each core ended up having very different consequences.

In the East, the internal migration that had created a new frontier beyond the Yangzi since the fifth century was the real motor behind social development. The restoration of a unified empire in the sixth century had accelerated development’s increase, and by the eighth century the upward trend was so robust that it survived the fallout from Xuanzong’s love life. Political chaos certainly had negative consequences; a sharp dip in the Eastern score in 900 (

Figure 7.1

), for instance, was largely the result of rival armies wiping out the million-strong city of Chang’an. But most fighting remained far from the vital rice paddies, canals, and cities, and may actually have accelerated development by sweeping away the government micromanagers who had previously hobbled commerce. Unable to supervise state-owned lands in such troubled times, civil servants started raising money from monopolies and taxes on trade and stopped telling merchants how to do business. There was a transfer of power from the political centers of northern China to the merchants of the south, and merchants, left to their own devices, figured out still more ways to speed up commerce.

Much of northern China’s overseas trade had been state-directed, between the imperial court and the rulers of Japan and Korea, and the collapse of Tang dynasty political power after 755 dissolved these links. Some results were positive; cut off from Chinese models, Japanese elite culture moved in remarkable and original directions, with a whole string of women writing literary masterpieces such as

The Tale of Genji

and

The Pillow Book

. Most results, though, were negative. In northern China, Korea, and Japan economic slowdown and state breakdown went together in the ninth century.

In southern China, by contrast, independent merchants exploited their new freedom from state power. Tenth-century shipwrecks found in the Java Sea since the 1990s contain not only Chinese luxuries but also pottery and glass from South Asia and the Muslim world, hinting at the expansion of markets in this region; and as local elites taxed the flourishing traders, the first strong Southeast Asian states emerged in what is now Sumatra and among the Khmers in Cambodia.

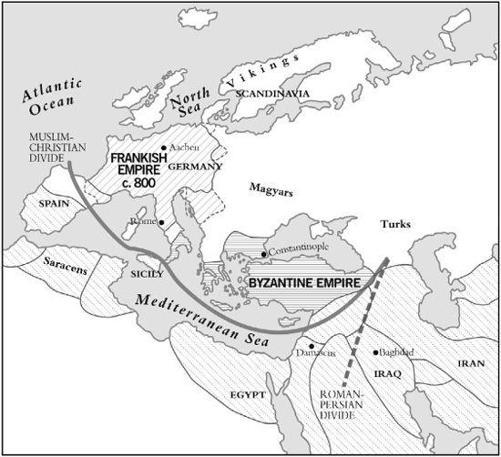

The very different geography of western Eurasia, with no equivalent to the East’s rice frontier, meant that its political breakdown also had different consequences. In the seventh century the Arab conquests swept away the old boundary that had separated the Roman world from the Persian (

Figure 7.7

), setting off something of a boom in the Muslim core. Caliphs expanded irrigation in Iraq and Egypt, and travelers carried crops and techniques from the Indus to the Atlantic. Rice, sugar, and cotton spread across the Muslim Mediterranean, and by alternating crops farmers got two or three harvests from their fields. The Muslims who colonized Sicily even invented classic Western foods such as pasta and ice cream.

However, the gains from overcoming the old barrier between Rome and Persia were increasingly offset by the losses caused by a new barrier across the Mediterranean, separating Islam from Christendom. As the southern and eastern Mediterranean grew more solidly Muslim (as late as 750, barely one person in ten under Arab rule was Muslim; by 950, it was more like nine in ten) and Arabic became its lingua franca, contact with Christendom declined; and then, as the caliphate fragmented after 800, emirs raised barriers within Islam, too. Some of the regions within the Muslim core, such as Spain, Egypt, and Iran, were big enough to get by on internal demand alone, but others declined.

Figure 7.7. The fault line shifts: the heavy dashes represent the major economic-political-cultural fault line between 100

BCE

and 600

CE

, separating Rome from Persia; the solid line shows the major line after 650

CE

, separating Islam from Christendom. At the top left is the Frankish Empire at its peak, around 800; at the bottom the Muslim world, showing the political divisions around 945.

And while China’s ninth-century wars had mostly avoided the economic heartlands, Iraq’s fragile irrigation network was devastated by competing Turkic slave armies and a fourteen-year uprising of African plantation slaves under a leader who at various times claimed to be a poet, a prophet, and a descendant of ‘Ali.

In the East, Korea and Japan drifted toward political breakdown when the northern Chinese core went into crisis; similarly, in the West the Christian periphery fragmented still further as the Muslim core came apart. Byzantines slaughtered one another by the thousands and

split from the Roman Church over new doctrinal questions (especially whether God approved of images of Jesus, Mary, and the saints), and the Germanic kingdoms, largely cut off from the Mediterranean, began creating their own world.

Some on this far western fringe expected it to become a core in its own right. Since the sixth century the Frankish people had become a regional power, and small trading towns now popped up around the North Sea to satisfy the Frankish aristocracy’s insatiable demand for luxuries. Theirs remained a low-end state, with little taxation or administration. Kings who were good at mobilizing their quarrelsome lords could quickly put together large but loose realms embracing much of western Europe, but under weak kings these equally quickly broke down. Kings with too many sons usually ended up dividing their lands among them—which often simply led to wars to reunite the patrimony.

The later eighth century was a particularly good time for the Franks. In the 750s the pope in Rome sought their protection against local bullies, and on Christmas morning, 800, the Frankish king Charlemagne

*

was even able to get Pope Leo III to kneel before him in St. Peter’s and crown him Roman emperor.

Charlemagne vigorously tried to build a kingdom worthy of the title he claimed. His armies carried fire, the sword, and Christianity into eastern Europe and pushed the Muslims back into Spain, while his literate bureaucracy gathered some taxes, assembled scholars at Aachen (“

a Rome

yet to be,” one of his court poets called it), created a stable coinage, and oversaw a trade revival. It is tempting to compare Charlemagne to Xiaowen, who, three centuries before, had moved the Northern Wei kingdom on China’s rough frontier toward the high end, jump-starting the process that led to the reunification of the Eastern core. Charlemagne’s coronation in Rome certainly speaks of ambitions like Xiaowen’s, as do the embassies he sent to seek Baghdad’s friendship. So impressed was the caliph, Frankish chronicles say, that he sent Charlemagne an elephant.

Arab sources, however, mention neither Franks nor elephants. Charlemagne was no Xiaowen, and apparently counted for little in the

caliph’s councils. Nor did Charlemagne’s claim to be Roman emperor move the Byzantine empress Irene

*

to abdicate in his favor. The reality was that the Frankish kingdom never moved very far toward the high end. For all Charlemagne’s pretensions, he had no chance of reuniting the core or even turning the Christian fringe into a single state.

One of the things Charlemagne did achieve, unfortunately, was to raise social development enough to lure raiders into his empire from the even wilder lands beyond the Christian periphery. By the time he died in 814, Viking longboats from Scandinavia were nosing up rivers into the empire’s heart, Magyars on tough little steppe ponies were plundering Germany, and Saracen pirates from North Africa were about to sack Rome itself. Aachen was ill equipped to respond; when Vikings beached their ships and burned villages, royal armies came late or not at all. Increasingly, countryfolk turned to local big men to defend them, and townspeople turned to their bishops and mayors. By the time Charlemagne’s three grandsons divided the empire among themselves in 843, kings had ceased to mean much to most of their subjects.

UNDER PRESSURE

As if these strains were not enough, after 900 Eurasia came under a new kind of pressure—literally; as Earth’s orbit kept shifting, atmospheric pressure increased over the landmass, weakening the westerlies blowing off the Atlantic into Europe and the monsoons blowing off the Indian Ocean into southern Asia. Averaged across Eurasia, temperatures probably rose 1–2°F between 900 and 1300 and rainfall declined by perhaps 10 percent.

As always, climate change forced people to adapt, but left it up to them to decide just how to do that. In cold, wet northern Europe this so-called Medieval Warm Period was often welcome, and population probably doubled between 1000 and 1300. In the hotter, drier Islamic core, however, it could be less welcome. Overall population in the Muslim world probably fell by 10 percent, but some areas, particularly

in North Africa, flourished. In 908 Ifriqiya,

*

roughly modern Tunisia (

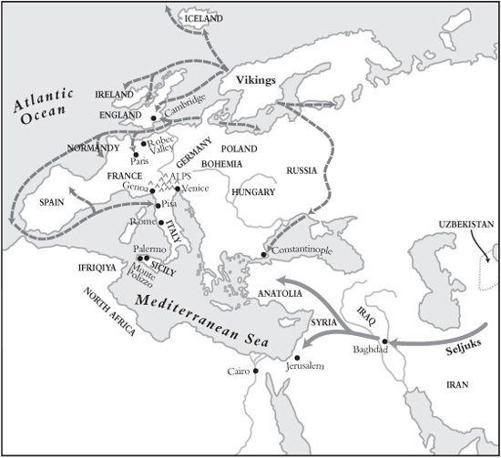

Figure 7.8

), broke away from the caliphs in Baghdad. Radical Shiites

†

set up a line of officially infallible caliph-imams, known as Fatimids because they claimed descent (and imamhood) from Muhammad’s daughter Fatima. In 969 these Fatimids conquered Egypt, where they built a great new city at Cairo and invested in irrigation. By 1000 Egypt had the highest social development in the West, and Egyptian traders were fanning out across the Mediterranean.

Figure 7.8. Coming in from the cold: the migrations of the Seljuk Turks (solid arrows) and Vikings/Normans (broken arrows) into the Western core in the eleventh century

We would know precious little about these traders had the Jewish community in Cairo not decided in 1890 to remodel its nine-hundred-year-old synagogue. Like many synagogues, this had a storeroom where worshippers could deposit unwanted documents to avoid risking blasphemy by destroying papers that might have God’s name written on them. Normally storerooms were cleared out periodically, but this one had been allowed to fill up with centuries’ worth of wastepaper. As the remodeling began, old documents started showing up in Cairo’s antiquities markets, and in spring 1896 two English sisters carried a bundle back to Cambridge. There they showed two texts to Solomon Schechter, the University Reader in Talmudics. Initially skeptical, Schechter then had an “Oh my God” moment: one was a Hebrew fragment of the biblical book of Ecclesiasticus, previously known only from Greek translations. The learned doctor descended on Cairo that December and carried off 140,000 documents.

Among them were hundreds of letters to Cairo trading houses, mailed between 1025 and about 1250 from as far afield as Spain and India. The ideological divisions that had formed in the wake of the Arab conquests were crumbling as population growth expanded markets and profits, and clearly meant little to these correspondents, who worried more about the weather, their families, and getting rich than about religion and politics. In this they may have been typical of Mediterranean merchants; though less well documented, commerce was apparently just as international and profitable in Ifriqiya and Sicily, where Muslim Palermo became a boomtown trading with Christian northern Italy.

Even Monte Polizzo, the backcountry Sicilian village where I have been excavating for the last few years, got into the act. As I mentioned in

Chapter 5

, I went there to study the effects of Phoenician and Greek colonization in the seventh and sixth centuries

BCE

, but when we started digging in 2000 we found a second village above the ancient houses. This second village had been established around 1000

CE

, probably by Muslim immigrants from Ifriqiya, and burned down around 1125. When our botanist sifted through the carbonized seeds excavated in its ruins, he discovered—to everyone’s surprise—that one building had been a storeroom full of carefully threshed wheat, with scarcely a weed in it.

*

This formed a sharp contrast with the seeds we

found in the sixth-century-

BCE

contexts, which were always mixed with plenty of weeds and chaff. That would have made for rather coarse bread, which is what we might expect in a simple farming village where people grew crops for their own tables and did not worry about the occasional unpleasant mouthful. The compulsive winnowing that rid the twelfth-century-

CE

wheat of all impurities, though, is exactly what we might expect from commercial farmers producing for picky city folk.