Why the West Rules--For Now (21 page)

Read Why the West Rules--For Now Online

Authors: Ian Morris

Tags: #History, #Modern, #General, #Business & Economics, #International, #Economics

EAST OF EDEN

Maybe so, the advocate of long-term lock-in theories might agree; maybe people really are much the same everywhere, and maybe geography did make Westerners’ jobs easier. Yet there is more to history than weather

and the size of seeds. Surely the details of the particular choices people made among working less, eating more, and raising bigger families matter too. The end of a story is often written in its beginning, and perhaps the West rules today because the culture created in the Hilly Flanks more than ten thousand years ago, the parent from which all subsequent Western societies descend, just had more potential than the cultures created in other core regions around the world.

Let us take a look, then, at the best-documented, oldest, and (in our own times) most powerful civilization outside the West, that which began in China. We need to find out how much its earliest farming cultures differed from those in the West and whether these differences set East and West off along different trajectories, explaining why Western societies came to dominate the globe.

Until recently archaeologists knew very little about early agriculture in China. Many scholars even thought that rice, that icon of Chinese cuisine in our own day, began its history in Thailand, not China. The discovery of wild rice growing in the Yangzi Valley in 1984 showed that rice could have been domesticated here after all, but direct archaeological confirmation remained elusive. The problem was that while bakers inevitably burn some of their bread, preserving charred wheat or barley seeds for archaeologists to find, boiling, the sensible way to cook rice, rarely has this result. Consequently it is much harder for archaeologists to recover ancient rice.

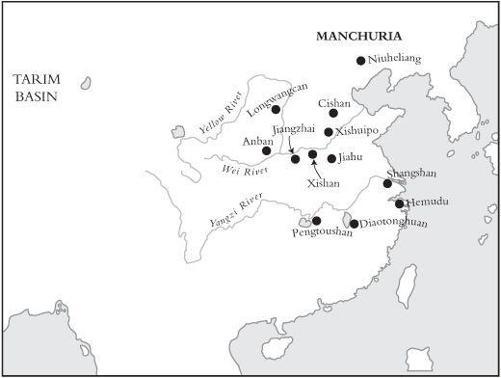

A little ingenuity, however, soon got archaeologists around this roadblock. In 1988 excavators at Pengtoushan in the Yangzi Valley (

Figure 2.7

) noticed that around 7000

BCE

potters began mixing rice husks and stalks into their clay to prevent pots cracking in the kiln, and close study revealed surefire signs that these plants were being cultivated.

The real breakthroughs, though, began in 1995, when Yan Wenming of Peking University

*

teamed up with the American archaeologist Richard MacNeish, as hardcore a fieldworker as any in the world. (MacNeish, who began digging in Mexico in the 1940s, logged an awe-inspiring 5,683 days in the trenches—nearly ten times what I have

managed to do; and when he died in 2001, aged eighty-two, it was with his boots on, in an accident while doing fieldwork in Belize. He reportedly talked archaeology with the ambulance driver all the way to the hospital.) MacNeish brought to China not only decades of expertise studying early agriculture but also the archaeobotanist Deborah Pearsall, who in turn brought a new scientific technique. Even though rice rarely survives in archaeological deposits, all plants absorb tiny amounts of silica from groundwater. The silica fills some of the plant’s cells, and when the plant decays it leaves microscopic cell-shaped stones, called phytoliths, in the soil. Careful study of phytoliths can reveal not just whether rice was being eaten but also whether it was domesticated.

Figure 2.7. The beginning of the East: sites in what is now China discussed in this chapter

Yan and MacNeish dug a sixteen-foot-deep trench in Diaotonghuan Cave near the Yangzi Valley, and Pearsall was able to show from phytoliths that by 12,000

BCE

people were uprooting wild rice and bringing it back to the cave. Rather like the Hilly Flanks, where wild wheat, barley, and rye flourished as the world warmed up, this was a hunter-gatherer golden age. There is no sign in the phytoliths that rice

was evolving toward domestic forms the way rye was evolving at Abu Hureyra, but the Younger Dryas was clearly just as devastating in the Yangzi Valley as in the West. Wild rice virtually disappeared from Diaotonghuan by 10,500

BCE

, only to return when the weather improved after 9600. Coarse pottery, probably vessels for boiling the grains, became common about that time (2,500 years before the first pottery from the Hilly Flanks). Around 8000

BCE

the phytoliths start getting bigger, a sure sign that people were cultivating the wild rice. By 7500

BCE

fully wild and cultivated grains were equally common at Diaotonghuan; by 6500, fully wild rice had disappeared.

A cluster of excavations in the Yangzi Delta since 2001 supports this timeline, and by 7000

BCE

people in the Yellow River valley had clearly begun cultivating millet. Jiahu, a remarkable site between the Yangzi and Yellow rivers, had cultivated rice and millet and perhaps also domesticated pigs by 7000

BCE

, and at Cishan a fire around 6000

BCE

scorched and preserved almost a quarter of a million pounds of large millet seeds in eighty storage pits. At the bottom of some pits, under the millet, were complete (presumably sacrificed) dog and pig skeletons, some of the earliest Chinese evidence for domesticated animals.

As in the West, domestication involved countless small changes across many centuries in a range of crops, animals, and techniques. The high water table at Hemudu in the Yangzi Delta has given archaeologists a bonanza, preserving huge amounts of waterlogged rice as well as wood and bamboo tools, all dating from 5000

BCE

onward. By 4000, rice was fully domesticated, as dependent on human harvesters as were wheat and barley in the West. Hemudans also had access to domesticated water buffalo and were using buffalo shoulder blades as spades. In northern China’s Wei Valley archaeologists have documented a steady shift from hunting toward full-blown agriculture after 5000

BCE

. This was clearest in the tools being used: stone spades and hoes replaced axes as people moved from simply clearing patches in the forest to cultivating permanent fields, and spades got bigger as farmers turned the soil more deeply. In the Yangzi Valley recognizable rice paddies, with raised banks for flooding, may go back as far as 5700

BCE

.

Early Chinese villages, like Jiahu around 7000

BCE

, looked quite like the first villages in the Hilly Flanks, with small, roughly round semisubterranean huts, grindstones, and burials between the houses.

Between fifty and a hundred people lived at Jiahu. One hut was slightly larger than the others but the very consistent distribution of finds suggests that wealth and gender distinctions were still weak and cooking and storage were communal. This was changing by 5000

BCE

, when some villages had 150 residents and were protected by ditches. At Jiangzhai, the best-documented site of this date, huts faced an open area containing two large piles of ash, which may be remains of communal rituals.

The Jiangzhai sacrifices—if such they are—look pretty tame compared to the shrines Westerners had already been building for several thousand years, but two remarkable sets of finds in graves at Jiahu suggest that religion and ancestors were every bit as important as in the Hilly Flanks. The first consists of thirty-plus flutes carved from the wing bones of red-crowned cranes, all found in richer-than-average male burials. Five of the flutes can still be played. The oldest, from around 7000

BCE

, had five or six holes, and while they were not very subtle instruments, modern Chinese folk songs can be played on them. By 6500

BCE

seven holes were normal and the flutemakers had standardized pitch, which probably means that groups of flautists were performing together. One grave of around 6000

BCE

held an eight-hole flute, capable of playing any modern melody.

All very interesting; but the flutes’ full significance becomes clear only in the light of twenty-four rich male graves containing turtle shells, fourteen of which had simple signs scratched on them. In one grave, dating around 6250

BCE

, the deceased’s head had been removed (shades of Çatalhöyük!) and replaced with sixteen turtle shells, two of them inscribed. Some of these signs—in the eyes of some scholars, at least—look strikingly like pictograms in China’s earliest full-blown writing system, used by the kings of the Shang dynasty five thousand years later.

I will come back to the Shang inscriptions in

Chapter 4

, but here I just want to observe that while the gap between the Jiahu signs (around 6250

BCE

) and China’s first proper writing system (around 1250

BCE

) is almost as long as that between the strange symbols from Jerf al-Ahmar in Syria (around 9000

BCE

) and the first proper writing in Mesopotamia (around 3300

BCE

), China has more evidence for continuity. Dozens of sites have yielded the odd pot with an incised sign, particularly after 5000

BCE

. All the same, specialists disagree fiercely over whether

the crude Jiahu scratchings are direct ancestors of the five-thousand-plus symbols of the Shang writing system.

Not the least of the arguments in favor of links is the fact that so many Shang texts were also scratched on turtle shells. Shang kings used these shells in rituals to predict the future, and traces of this practice definitely go back to 3500

BCE

; could it be, the excavators of Jiahu now ask, that the association of turtle shells, writing, ancestors, divination, and social power began before 6000

BCE

? As anyone who has read Confucius knows, music and rites went together in first-millennium-

BCE

China; could the flutes, turtle shells, and writing in the Jiahu graves be evidence that ritual specialists able to talk to the ancestors emerged more than five thousand years earlier?

That would be a remarkable continuity, but there are parallels. Earlier in the chapter I mentioned the peculiar twin-headed statues with giant staring eyes, dating around 6600

BCE

, found at ‘Ain Ghazal in Jordan; Denise Schmandt-Besserat, an art historian, has pointed out that descriptions of the gods written down in Mesopotamia around 2000

BCE

are strikingly like these statues. In East and West alike, some elements of the first farmers’ religions may have been extremely long-lived.

Even before the discoveries at Jiahu, Kwang-chih Chang of Harvard University—the godfather of Chinese archaeology in America from the 1960s until his death in 2001—had suggested that the first really powerful people in China had been shamans who persuaded others that they could talk to animals and ancestors, fly between worlds, and monopolize communication with the heavens. When Chang presented this theory, in the 1980s, the evidence available only allowed him to trace such specialists back to 4000

BCE

, a time when Chinese societies were changing rapidly and some villages were turning into towns. By 3500

BCE

some communities had two or three thousand residents, as many as Çatalhöyük or ‘Ain Ghazal had had three thousand years earlier, and a handful of communities could mobilize thousands of laborers to build fortifications from layer upon layer of pounded earth (good building stone is rare in China). The most impressive wall, at Xishan, was ten to fifteen feet thick and ran for more than a mile. Even today it still stands eight feet high in places. Parts of children’s skeletons in clay jars under the foundations may have been sacrifices, and numerous pits full of ash within the settlement contained adults in poses suggesting

struggle, sometimes mixed with animal bones. These may have been ritual murders like those from Çayönü in Turkey, and there is some evidence that such grisly rites go back to 5000

BCE

in China.

If Chang was right that shamans were taking on leadership roles by 3500

BCE

, they may have lived in the large houses, covering up to four thousand square feet, that now appeared in some towns (archaeologists often call these “palaces,” though that is a bit grandiose). These had plastered floors, big central hearths, and ash pits holding animal bones (from sacrifices?). One contained a white marble object that looks like a scepter. The most interesting “palace,” at Anban, stood on high ground in the middle of the town. It had stone pillar bases and was surrounded by pits full of ash, some holding pigs’ jaws that had been painted red, others pigs’ skulls wrapped in cloth, and others still little clay figurines with big noses, beards, and odd pointed hats (much like Halloween witches).

Two things about these statuettes get archaeologists excited. First, the tradition of making them lasted for thousands of years, and a very similar model found in a palace dating around 1000

BCE

had the Chinese character

wu

painted on its hat.

Wu

meant “religious mediator,” and some archaeologists conclude that all these figurines, including the ones from Anban, must represent shamans. Second, many of the figurines look distinctly Caucasian, not Chinese. Similar models have been found all the way from Anban to Turkmenistan in central Asia along the path that later became the Silk Road, linking China to Rome. Shamanism remains strong in Siberia even today; for a price, ecstatic visionaries will still summon up spirits and predict the future for adventurous tourists. The Anban figurines might indicate that shamans from the wilds of central Asia were incorporated into Chinese traditions of religious authority around 4000

BCE

; they might, some archaeologists think, even mean that the shamans of the Hilly Flanks, going back to 10,000

BCE

, had some very distant influence on the East.