Why the West Rules--For Now (101 page)

Read Why the West Rules--For Now Online

Authors: Ian Morris

Tags: #History, #Modern, #General, #Business & Economics, #International, #Economics

WAR-MAKING

Since writing began, people have recorded their wars, and since early prehistory have often buried their dead with weapons. As a result we know a surprising amount even about premodern warfare. The major challenge in scoring war-making capacity is not empirical but conceptual—how we compare radically different fighting systems that are often intended to be incomparable with earlier systems. Most famously, when Britain launched HMS

Dreadnought

in 1906, the whole idea was that its supersized guns and heavy armor meant that no number of 1890-era ships would add up to one post-1906 ship.

The reality, though, is that things never work out so simply. Improvised explosive devices can, under the right circumstances, give even the highest-tech army a run for its money. In principle we can assign scores on a single index to wildly different military systems, even if experts might argue over what those scores should be.

In 2000

CE,

the West’s unprecedented military power earns 250 points, and is clearly much greater than the East’s. Some Eastern armies are large, but weapons systems matter far more than sheer numbers. The United States outspends China 10:1, and outnumbers it 11:0 in carrier groups and 26:1 in nuclear warheads. The qualitative differences between America’s M1 battle tanks and precision weapons and China’s outdated systems are still greater. Setting the West:East points ratio as low as 10:1 or as high as 50:1 both seem extreme, and I have guessed at 20:1, meaning that the East scores 12.5 points in 2000 as against the West’s 250.

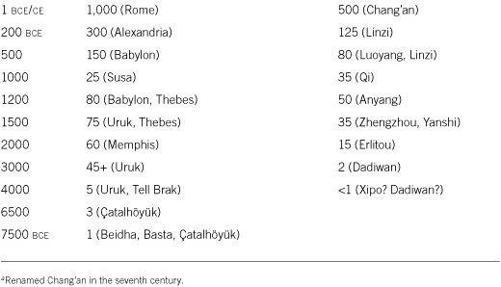

Table A.2. Population of the largest settlement in each core, thousands (selected dates)

Comparing scores in 2000 with those in earlier periods is even more difficult, but by looking at the changes in the size of forces, the speed of their movement, their logistical capacities, the range and destructiveness of their striking power, and the armor and fortifications at their disposal, we can make rough estimates. According to one calculation, the effectiveness of artillery fire increased twentyfold between 1900 and 2000 and that of antitank fire sixtyfold; factoring in all the other changes across the twentieth century, I set the ratio between Western war-making capacity in 2000 and 1900 at 50:1, meaning that the West scores 5 points in 1900 compared with its 250 points in 2000.

Western military power in 1900 was much greater than Eastern, though the gap was certainly not as large as it was by 2000. The British navy had nearly six times the tonnage of the Japanese in 1902, and any one of Europe’s great powers had more men under arms than Japan; I set the West:East ratio in 1900 at 5:1, meaning that the East scores just 1 point in 1900 (as compared with the West’s 5 points in 1900 and the East’s 12.5 points in 2000).

Not everyone will be comfortable with the level of subjectivity in calculations such as these, but the important point is that the West’s military capacity in 2000 was so enormous that all other scores—including the West’s in 1900 or even the East’s in 2000—are necessarily tiny; and, as a result of this, the errors involved in estimation are insignificant. We could double, or cut in half, any or all of the war-making scores for all periods up to 1900 without having a noticeable impact on the total development scores.

The contrast between Western war-making in 1800 and that in 1900 was less than the contrast between 1900 and 2000, but it was still enormous, taking us from the age of sail, cavalry charges, and smoothbore muzzle-loaded muskets to that of explosive shells, armored oil-powered ships, and machine guns, with tanks and aircraft just around the corner. The nineteenth century probably raised Western war-making capacity by an order of magnitude, and I set the West’s war-making capacity at just 0.5 point in 1800. Western warfare at that point was vastly more effective than Eastern, which should perhaps earn just 0.1 point in 1800.

Between 1500 and 1800 Europe went through what historians commonly call a “military revolution,” perhaps quadrupling the effectiveness

of its war-making. Eastern war-making, by contrast, actually went backward between 1700 (when Kangxi began conquering the steppes) and 1800. In the absence of existential threats, Chinese rulers regularly sought peace dividends by reducing their armed forces and ignoring expensive technological advances. Eastern war-making was not noticeably more effective in 1800 than it had been in 1500, and was much

less

effective than it had been in 1700—which has a lot to do with why Britain’s forces swept China’s aside so easily in the 1840s.

The advent of gunpowder weapons in the fourteenth century increased war-making capacity in both East and West, though much less dramatically than the inventions of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries would do. In Europe the best armies around 1500 (particularly the Ottomans) were probably twice as effective as those of five centuries earlier, though that had as much to do with size and logistics as with firepower.

The relationship between Western war-making around 1500 and the large, highly organized, but pre-gunpowder forces of the Roman Empire is harder to calculate. One study has estimated that a single

jet bomber

around 2000

CE

had half a million times the killing capacity of a Roman legionary, which we might take as implying that the Western score in 1

BCE/CE

would be 0.0005 point; but of course Rome had far more legionaries than the United States has jet bombers, and I estimate the ratio between modern Western and Roman war-making at more like 2,000:1, putting the Western score in 1

BCE

/

CE

at 0.12 point. That makes the Roman war machine at its height a serious rival for fifteenth-century European armies and navies, despite their guns and cannons, but not for the forces of the “military revolution” era. It also means that Roman war-making at its zenith might have competed with that of the Mongols and was superior to that of Tang dynasty China.

In the East, where bronze weapons were still the norm as late as 200

BCE

, Han dynasty (200

BCE

–200

CE

) forces seem to have been less effective than Roman, although Chinese military power declined much less than Western after the Old World Exchange. The armies and navies that the Sui used to reunite China in the sixth century were much stronger than anything in the West, and by the time of Empress Wu around 700 the gap was enormous.

The militaries of the centuries

BCE

were much weaker than those of the Roman and Han empires. In the East I assume that no force before the time of Erlitou around 1900

BCE

was effective enough to score 0.01 point; in the West, Egyptian and Mesopotamian armies probably scored 0.01 point by about 3000

BCE

.

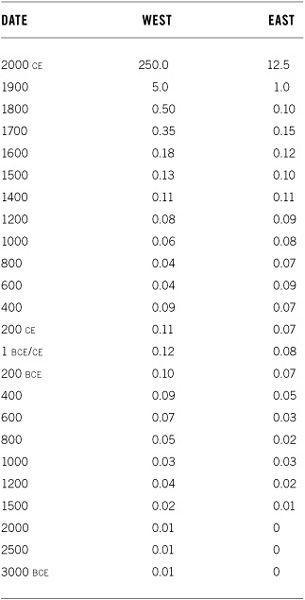

Table A.3. War-making capacity, expressed in points on the social development index (selected dates)

INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY

Archaeological and written sources show us what kinds of information technology existed at various periods and it is not too difficult to estimate how much information these media could communicate, at what speeds, and over what distances. The real problem lies in estimating the extent of use of different technologies, which through most of history means how many people could read and write and at what levels of competence.

Moore’s Law—that the cost-effectiveness of information technology has doubled every eighteen months or so since about 1950—seems to imply that the score in 2000 should be about a billion times higher than that of 1900, giving us a Western score in 1900 of 0.00000025 point. But that, of course, would overlook both the flexibility of old-fashioned forms of information storage such as printed books (which digital media are only now beginning to challenge) and changes over time in access to the most advanced techniques.

The correct ratio between modern and earlier information technology is much less than a billion to one, though it is clearly enormous, with the consequence that pre-1900 scores (and even more so, pre-1900 margins of error) are even tinier than in the case of war-making. On the other hand, the evidence for just how many people could read, write, and count at various levels of skill is much vaguer than the evidence for war, and my guesstimates are even more impressionistic.

In

table A.4

I take a multistep approach to quantifying information technology. First, following common practice among historians, I divide skills into full, medium, and basic. The bars for each category are set low—in terms of literacy, basic means being able to read and write a name; medium, being able to read or write a simple sentence; and full, being able to read and write more connected prose. The Chinese Communist Party’s definitions in its 1950 literacy drive (full literacy, being able to recognize 1,000 characters; semiliteracy, recognizing 500–1,000; basic, 300–500) were rather similar.

Second, drawing on the available scholarship, I divide the adult male population at different periods across these three categories. For each 1 percent of men that falls into the full-literacy category I assign 0.5 point; for each percent in the medium category, 0.25 point; and for each percent in the basic category, 0.15 point. I then assign the same scores to women. The evidence for female literacy is poorer than for male, though it is clear that until the twentieth century fewer (usually far fewer) women than men could read and write. Although I am basically guessing before recent times, I hazard estimates of female use of information technology as a percentage of male use. I then assign points to each period based on the amount and level of information technology use.

In 2000, 100 percent of men and women are in the full category in both the Western and Eastern cores,

*

scoring 100 information technology points for both regions. In 1900, nearly all men in the Western core had at least some literacy (50 percent full, 40 percent medium, and 7 percent basic) and women were almost as well educated, generating a Western score of 63.8 IT points. In the East literacy was also widespread among men, though not at such high levels (I estimate 15 percent full, 60 percent medium, and 10 percent basic), though literate women may have been only a quarter as common. The result is an Eastern score of 30 IT points. As I repeat these calculations further back in history, the possible margin of error around my guesses steadily increases, although the tiny numbers of literate people make the impact of these errors correspondingly small.

The third step is to apply a multiplier for the changing speed and reach of communication technologies. I divide the most advanced tools for handling information into three broad categories: electronic (in use in both East and West by 2000), electrical (in use in the West by 1900), and preelectrical (in use in the West for perhaps eleven thousand years and in the East for perhaps nine thousand years).

Unlike most historians I do not make a strong distinction between print and preprint eras; the main contribution of printing was to produce more and cheaper materials rather than to transform communication the way that the telegraph or Internet would do, and these quantitative changes have already been factored in. For electronic technologies, I use a multiplier of 2.5 for the West and 1.89 for the East, reflecting the relative availability of computers and broadband communication in West and East in the year 2000. For electrical technologies, having some impact in the West by 1900, I use a multiplier of 0.05; and for preelectrical technologies, in use in all other periods, I use a multiplier of 0.01 in both East and West. Consequently, in 2000 the West scores the maximum possible 250 social development points (100 IT points × 2.5) and the East gets 189 (100 IT points × 1.89); in 1900, the West scores 3.19 points (63.8 × 0.05) and the East 0.3 (30 × 0.01). The Western score reaches the minimum level necessary to register on the index of social development (that is, 0.01 point) only around 3300

BCE

; the Eastern, around 1300

BCE

.