Why People Believe Weird Things: Pseudoscience, Superstition, and Other Confusions of Our Time (8 page)

Authors: Michael Shermer

Tags: #Creative Ability, #Parapsychology, #Psychology, #Epistemology, #Philosophy & Social Aspects, #Science, #Philosophy, #Creative ability in science, #Skepticism, #Truthfulness and falsehood, #Pseudoscience, #Body; Mind & Spirit, #Belief and doubt, #General, #Parapsychology and science

The Tool of the Mind

Vincent Dethier, in his discussion of the rewards of science, runs through a pantheon of the obvious ones—money, security, honor—as well as the transcendent: "a passport to the world, a feeling of belonging to one race, a feeling that transcends political boundaries and ideologies, religions, and languages." But he brushes all these aside for one "more lofty and more subtle"—the natural curiosity of humans:

One of the characteristics that sets man apart from all the other animals (and animal he indubitably is) is a need for knowledge for its own sake. Many animals are curious, but in them curiosity is a facet of adaptation. Man has a hunger to know. And to many a man, being endowed with the capacity to know, he has a duty to know. All knowledge, however small, however irrelevant to progress and well-being, is a part of the whole. It is of this the scientist partakes. To know the fly is to share a bit in the sublimity of Knowledge. That is the challenge and the joy of science. (1962, pp. 118-119)

At its most basic level, curiosity about how things work is what science is all about. As Feynman observed, "I've been caught, so to speak—like someone who was given something wonderful when he was a child, and he's always looking for it again. I'm always looking, like a child, for the wonders I know I'm going to find—maybe not every time, but every once in a while" (1988, p. 16). The most important question in education, then, is this: What tools are children given to help them explore, enjoy, and understand the world? Of the various tools taught in school, science and thinking skeptically about all claims should be near the top.

Children are born with the ability to perceive cause-effect relations. Our brains are natural machines for piecing together events that may be related and for solving problems that require our attention. We can envision an ancient hominid from Africa chipping and grinding and shaping a rock into a sharp tool for carving up a large mammalian carcass. Or perhaps we can imagine the first individual who discovered that knocking flint would create a spark that would light a fire. The wheel, the lever, the bow and arrow, the plow—inventions intended to allow us to shape our environment rather than be shaped by it—started us down a path that led to our modern scientific and technological world.

On the most basic level, we must think to remain alive. To think is the most essential human characteristic. Over three centuries ago, the French mathematician and philosopher Rene Descartes, after one of the most thorough and skeptical purges in intellectual history, concluded that he knew one thing for certain:

"Cogito ergo sum—I think therefore I am."

But to be human is to think. To reverse Descartes,

"Sum ergo cogito—I am therefore I think."

2

The Most Precious Thing We Have

The Difference Between Science and Pseudoscience

The part of the world known as the Industrial West could, in its entirety, be seen as a monument to the Scientific Revolution, begun over 400 years ago and succinctly captured in a single phrase by one of its initiators, Francis Bacon: "Knowledge itself is power." We live in an age of science and technology. Thirty years ago, historian of science Derek J. De Solla Price observed that "using any reasonable definition of a scientist, we can say that 80 to 90 percent of all the scientists that have ever lived are alive now. Alternatively, any young scientist, starting now and looking back at the end of his career upon a normal life span, will find that 80 to 90 percent of all scientific work achieved by the end of the period will have taken place before his very eyes, and that only 10 to 20 percent will antedate his experience" (1963, pp. 1-2).

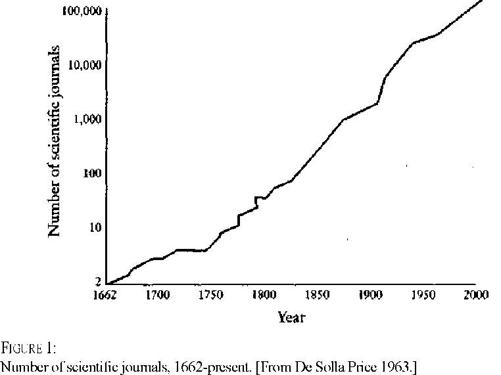

There are now, for example, more than six million articles published in well over 100,000 scientific journals each year. The Dewey Decimal Classification now lists more than a thousand different classifications under the heading "Pure Science," and within each of these classifications are dozens of specialty journals. Figure 1 depicts the growth in the number of scientific journals, from the founding of the Royal Society in 1662 when there were two, to the present.

Virtually every field of learning shows such an exponential growth curve. As the number of individuals working in a field grows, so too does the amount of knowledge, which creates more jobs, attracts more people, and so on. The membership growth curves for the American Mathematical Society (founded in 1888) and the Mathematical Association of America (founded in 1915), which are shown in figure 2, dramatically demonstrate this phenomenon. In 1965, observing the accelerating rate at which individuals were entering the sciences, the junior minister of science and education of Great Britain concluded, "For more than 200 years scientists everywhere were a significant minority of the population. In Britain today they outnumber the clergy and the officers of the armed forces. If the rate of progress which has been maintained ever since the time of Sir Isaac Newton were to continue for another 200 years, every man, woman and child on Earth would be a scientist, and so would every horse, cow, dog, and mule" (in Hardison 1988, p. 14).

Transportation speed has also shown geometric progression, with most of the change being made in the last 1 percent of human history. French historian Fernand Braudel tells us, for example, that "Napoleon moved no faster than Julius Caesar" (1981, p. 429). But in the twentieth century the speed of transportation has increased astronomically (figuratively and literally), as the following list shows:

1784 Stagecoach | 10 mph |

1825 Steam Locomotive | 13 mph |

1870 Bicycle | 17 mph |

1880 Steam-powered Train | 100 mph |

1906 Steam-powered Automobile | 127 mph |

1919 Early aircraft | 164 mph |

1938 Airplane | 400 mph |

1945 Combat airplane | 606 mph |

1947 Bell X-1 rocket-plane | 769 mph |

1960 Rocket | 4,000 mph |

1985 Space shuttle | 18,000 mph |

2000 TAU deep-space probe | 225,000 mph |

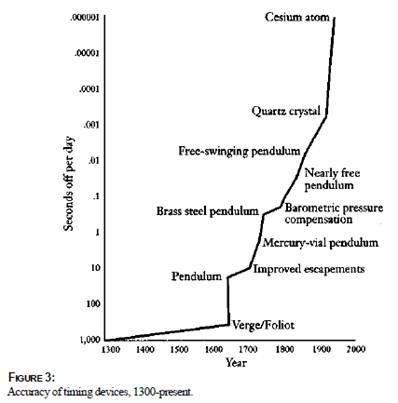

One final example of technological change based on scientific research will serve to drive the point home. Timing devices in various forms—dials, watches, and clocks—have improved exponentially in accuracy, as illustrated in figure 3.

If we are living in the Age of Science, then why do so many pseudo-scientific and nonscientific beliefs abound? Religions, myths, superstitions, mysticisms, cults, New Age ideas, and nonsense of all sorts have penetrated every nook and cranny of both popular and high culture. A 1990 Gallup poll of 1,236 adult Americans showed percentages of belief in the paranormal that are alarming (Gallup and Newport 1991, pp. 137-146).

Astrology | 52% |

Extrasensory perception | 46% |

Witches | 19% |

Aliens have landed on Earth | 22% |

The lost continent of Atlantis | 33% |

Dinosaurs and humans lived simultaneously | 41% |

Noah’s flood | 65% |

Communication with the dead | 42% |

Ghosts | 35% |

Actually had a psychic experience | 67% |

Other popular ideas of our time that have little to no scientific support include dowsing, the Bermuda Triangle, poltergeists, biorhythms, creationism, levitation, psychokinesis, astrology, ghosts, psychic detectives, UFOs, remote viewing, Kirlian auras, emotions in plants, life after death, monsters, graphology, crypto-zoology, clairvoyance, mediums, pyramid power, faith healing, Big Foot, psychic prospecting, haunted houses, perpetual motion machines, antigravity locations, and, amusingly, astrological birth control. Belief in these phenomena is not limited to a quirky handful on the lunatic fringe. It is more pervasive than most of us like to think, and this is curious considering how far science has come since the Middle Ages. Shouldn't we know by now that ghosts cannot exist unless the laws of science are faulty or incomplete?

Pirsig's Paradox

There is a priceless dialogue between father and son in Robert Pirsig's classic 1974 intellectual adventure story,

Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance,

that takes place during a cross-country motorcycle tour that included many late-night discussions. The father tells his son that he does not believe in ghosts because "they are unscientific. They contain no matter and have no energy and therefore according to the laws of science, do not exist except in people's minds. Of course, the laws of science contain no matter and have no energy either and therefore do not exist except in people's minds. It's best to refuse to believe in either ghosts or the laws of science." The son, now confused, wonders if his father has wandered off into nihilism (1974, pp. 38-39):

"So you don't believe in ghosts or science?"

"No, I do believe in ghosts." "What?"

"The laws of physics and logic, the number system, the principle of algebraic substitution. These are ghosts. We just believe in them so thoroughly they seem real. For example, it seems completely natural to presume that gravitation and the law of gravity existed before Isaac Newton. It would sound nutty to think that until the seventeenth century there was no gravity."

"Of course."

"So, before the beginning of the Earth, before people, etc., the law of gravity existed. Sitting there, having no mass of its own, no energy, and not existing in anyone's mind."

"Right."

"Then what has a thing to do to be nonexistent? It has just passed every test of nonexistence there is. You cannot think of a single attribute of nonexistence that the law of gravity didn't have, or a single scientific attribute of existence it did have. I predict that if you think about it long enough, you will go round and round until you realize that the law of gravity did not exist before Isaac Newton. So the law of gravity exists nowhere except in people's heads. It is a ghost!"

This is what I call

Pirsig's Paradox.

One of the knottier problems for historians and philosophers of science over the past three decades has been resolving the tension between the view of science as a progressive, culturally independent, objective quest for Truth and the view of science as a nonprogressive, socially constructed, subjective creation of knowledge. Philosophers of science label these two approaches

internalist

and

externalist,

respectively. The

internalist

focuses on the internal workings of science independent of its larger cultural context: the development of ideas, hypotheses, theories, and laws, and the internal logic within and between them. The Belgian-American George Sarton, one of the founders of the history of science field, launched the internalist view. Sarton's discussion of the internalist approach may be summarized as follows: