Why People Believe Weird Things: Pseudoscience, Superstition, and Other Confusions of Our Time (15 page)

Authors: Michael Shermer

Tags: #Creative Ability, #Parapsychology, #Psychology, #Epistemology, #Philosophy & Social Aspects, #Science, #Philosophy, #Creative ability in science, #Skepticism, #Truthfulness and falsehood, #Pseudoscience, #Body; Mind & Spirit, #Belief and doubt, #General, #Parapsychology and science

Who was Edgar Cayce? According to A.R.E. literature, Cayce was born in 1877 on a farm near Hopkinsville, Kentucky. As a youth, he "displayed powers of perception which extended beyond the five senses. Eventually, he would become the most documented psychic of all times." Purportedly, when he was twenty-one, Cayce's doctors were unable to find a cause or cure for a "gradual paralysis which threatened the loss of his voice." Cayce responded by going into a "hypnotic sleep" and recommended a cure for himself, which he claims worked. The discovery of his ability to diagnose illnesses and recommend solutions while in an altered state led him to do this on a regular basis for others with medical problems. This, in turn, expanded into general psychic readings on thousands of different topics covering every conceivable aspect of the universe, the world, and humanity.

Numerous books have been written on Edgar Cayce, some by uncritical followers (Cerminara 1967; Stearn 1967) and others by skeptics (Baker and Nickell 1992; Gardner 1952; Randi 1982). Skeptic Martin Gardner demonstrates that Cayce was fantasy-prone from his youth, often talking with angels and receiving visions of his dead grandfather. Uneducated beyond the ninth grade, Cayce acquired his broad knowledge through voracious reading, and from this he wove elaborate tales and gave detailed diagnoses while in his trances. His early psychic readings were done in the presence of an osteopath, from whom he borrowed much of his terminology. When his wife got tuberculosis, Cayce offered this diagnosis: "The condition in the body is quite different from what we have had before ... from the head, pains along through the body from the second, fifth and sixth dorsals, and from the first and second lumbar... tie-ups here, and floating lesions, or lateral lesions, in the muscular and nerve fibers." As Gardner explains, "This is talk which makes sense to an osteopath, and to almost no one else" (1952, p. 217).

In Cayce, James Randi sees all the familiar tricks of the psychic trade: "Cayce was fond of expressions like 'I feel that...' and 'perhaps'—qualifying words used to avoid positive declarations" (1982, p. 189). Cayce's remedies read like prescriptions from a medieval herbalist: for a leg sore, use oil of smoke; for a baby with convulsions, a peach-tree poultice; for dropsy, bedbug juice; for arthritis, peanut oil massage; and for his wife's tuberculosis, ash from the wood of a bamboo tree. Were Cayce's readings and diagnoses correct? Did his remedies work? It is hard to say. Testimony from a few patients does not represent a controlled experiment, and among his more obvious failures are several patients who died between the time of writing to Cayce and Cayce's reading. In one such instance, Cayce did a reading on a small girl in which he recommended a complex nutritional program to cure the disease but admonished, "And this depends upon whether one of the things as intended to be done today is done or isn't done, see?" The girl had died the day before, however (Randi 1982, pp. 189-195).

It was, then, with considerable anticipation that we passed under the words "That we may make manifest the love of God and man" and entered into the halls of Edgar Cayce's legacy. Inside there were no laboratory rooms and no scientific equipment save an ESP machine proudly displayed against a wall in the entrance hall (see figure 4). A large sign next to the machine announced that shortly there would be an ESP experiment in an adjacent room. We saw our opportunity.

The ESP machine featured the standard Zener cards (created by K. E. Zener, they display easily distinguished shapes to be interpreted in Psi experiments), with a button to push for each of the five symbols—plus sign, square, star, circle, and wavy lines. One of the directors of A.R.E. began with a lecture on ESP, Edgar Cayce, and the development of psychic powers. He explained that some people are born with a psychic gift while others need practice, but we all have the power to some degree. When he asked for participants, I volunteered to be a receiver. I was given no instruction on how to receive psychic messages, so I asked. The instructor explained that I should concentrate on the sender's forehead. The thirty-four other people in the room were told to do the same thing. We were all given an ESP Testing Score Sheet (see figure 5), with paired columns for our psychic choices and the correct answers, given after the experiment. We ran two trials of 25 cards each. I got 7 right in the first set, for which I honestly tried to receive the message, and 3 right in the second set, for which I marked the plus sign for every card.

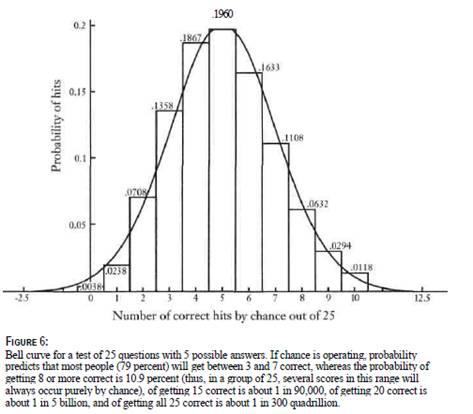

The instructor explained that "5 right is average, chance is between 3 and 7, and anything above 7 is evidence of ESP." I asked, "If 3 to 7 is chance, and anything above 7 is evidence of ESP, what about someone who scores below a 3?" The instructor responded, "That's a sign of negative ESP." (He didn't say what that was.) I then surveyed the group. In the first set, three people got 2 right, while another three got 8 right; in the second set, one even got 9 right. So, while I apparently did not have psychic power, at least four other people did. Or did they?

Before concluding that high scores indicate a high degree of ESP ability, you have to know what kind of scores people would get purely by chance. The scores expected by chance can be predicted by probability theory and statistical analysis. Scientists use comparisons between statistically predicted test results and actual test results to determine whether results are significant, that is, better than what would be expected by chance. The ESP test results clearly matched the expected pattern for random results.

I explained to the group, "In the first set, three got 2, three got 8, and everyone else [twenty-nine people] scored between 3 and 7. In the second set, there was one 9, two 2s, and one 1,

all scored by different people than those who scored high and low in the first test

Doesn't that sound like a normal distribution around an average of 5?" The instructor turned and said, with a smile, "Are you an engineer or one of those statisticians or something?" The group laughed, and he went back to lecturing about how to improve your ESP with practice.

When he asked for questions, I waited until no one else had any and then inquired, "You say you've been working with A.R.E. for several decades, correct?" He nodded. "And you say that with experience one can improve ESP, right?" He immediately saw where I was going and said, "Well. . .," at which point I jumped in and drew the conclusion, "By now you must be very good at this sort of test. How about we send the signals to you at the machine. I'll bet you could get at least 15 out of the 25." He was not amused at my suggestion and explained to the group that he had not practiced ESP in a long time and, besides, we were out of time for the experiment. He quickly dismissed the group, upon which a handful of people surrounded me and asked for an explanation of what I meant by "a normal distribution around an average of 5."

On a piece of scrap paper, I drew a crude version of the normal frequency curve, more commonly known as the bell curve (see figure 6). I explained that the mean, or average number, of correct responses ("hits") is expected by chance to be 5 (5 out of 25). The amount that the number of hits will deviate from the standard mean of 5, by chance, is 2. Thus, for a group this size, we should not put any special significance on the fact that someone got 8 correct or someone scored only 1 or 2 correct hits. This is exactly what is expected to happen by chance.

So these test results suggest that nothing other than chance was operating. The deviation from the mean for this experiment was nothing more than what we would expect. If the audience were expanded into the millions, say on a television show, there would be an even bigger opportunity for misinterpretation of the high scores. In this scenario, a tiny fraction would be 3 standard deviations above the mean, or get 11 hits, a still smaller percentage would reach 4 standard deviations, or 13 hits, and so on, all as predicted by chance and the randomness of large numbers. Believers in psychic power tend to focus on the results of the most deviant subjects (in the statistical sense) and tout them as the proof of the power. But statistics tells us that given a large enough group, there should be someone who will score fairly high. There may be lies and damned lies, but statistics can reveal the truth when pseudoscience is being flogged to an unsuspecting group.

After the ESP experiment, one woman followed me out of the room and said, "You're one of those skeptics, aren't you?"

"I am indeed," I responded.

"Well, then," she retorted, "how do you explain coincidences like when I go to the phone to call my friend and she calls me? Isn't that an example of psychic communication?"

"No, it is not," I told her. "It is an example of statistical coincidences. Let me ask you this: How many times did you go to the phone to call your friend and she did not call? Or how many times did your friend call you but you did not call her first?"

She said she would have to think about it and get back to me. Later, she found me and said she had figured it out: "I only remember the times that these events happen, and I forget all those others you suggested."

"Bingo!" I exclaimed, thinking I had a convert. "You got it. 'It is just selective perception."

But I was too optimistic. "No," she concluded, "this just proves that psychic power works sometimes but not others."

As James Randi says, believers in the paranormal are like "unsinkable rubber ducks."

5

Through the Invisible

Near-Death Experiences and the Quest for Immortality

I sent my Soul through the Invisible,

some letter of that After-life to spell:

And by and by my Soul return'd to me,

And answer'd "I Myself am Heav'n and Hell."

—Omar Khayyam,

The Rubaiyat

In 1980 I attended a weekend seminar in Klamath Falls, Oregon, on "Voluntary Controls of Internal States," hosted by Jack Schwarz, a man well known to practitioners of alternative medicine and altered states of consciousness. According to literature advertising the seminar, Jack is a survivor of a Nazi concentration camp, where years of isolation, miserable conditions, and physical torture taught him to transcend his body and go to a place where he could not be hurt. Jack's course was intended to teach the principles of mind control through meditation. Mastery of these principles allows one to voluntarily control such bodily functions as pulse rate, blood pressure, pain, fatigue, and bleeding. In a dramatic demonstration, Jack took out a ten-inch-long rusted sail needle and shoved it through his biceps. He didn't wince and after he pulled it out only a tiny drop of blood covered the hole. I was impressed.

The first part of the course was educational. We learned about the color, location, and power of our chakras (energy centers intersecting the physical and psychospiritual realms), the power of the mind to control the body through use of these chakras, the cure of illnesses through visualization, becoming at one with the universe through the interaction of matter and energy, and other remarkable things. The second part of the course was practical. We learned how to meditate, and then we chanted a type of mantra to focus our energies. This went on for quite some time. Jack explained that some people might experience some startling emotions. I didn't, try as I might, but others certainly did. Several women fell off their chairs and began writhing on the floor, breathing heavily and moaning in what appeared to me as an orgasmic state. Even some men really got into it. To help me get in tune with my chakras, one woman took me into a bathroom with a wall mirror, closed the door and shut off the lights, and tried to show me the energy auras surrounding our bodies. I looked as hard as I could but didn't see anything. One night we were driving along a quiet Oregon highway and she started pointing out little light-creatures on the side of the road. I couldn't see these either.