Why Men Want Sex and Women Need Love (6 page)

Read Why Men Want Sex and Women Need Love Online

Authors: Barbara Pease

Some things haven’t changed in a million years

.

S

o why do we even have sex in the first place? You might think either that there is a blindingly obvious answer or that it’s a stupid question. Think about it—sex, romance, and love affairs are all time-consuming and expensive pursuits. Dinners, holidays, endless phone calls and texts, lavish gifts, marriage, separation, and divorce all take time and cost money. And for what? The reason is the continuation of your genetic line—and that’s about it. It’s all to perpetuate your DNA. For humans, sex, which is hardwired, also serves several side purposes—it’s used to gain power and status and to play or to bond with others, as is the case with other primates, such as bonobo monkeys. But not all living things have sex to reproduce. Some plants, bacteria, and simple invertebrates, such as worms, don’t have sex—they simply clone themselves

to reproduce. This is known as being asexual. The problem is that cloning produces offspring that are identical to the parent but are not stronger or better adapted; the offspring are therefore less likely to survive changing environments. An asexual female’s offspring can survive only in the same habitat their mother was adapted to,

1

but environments are always changing. By mixing the genes of two individuals, you can produce offspring that are stronger and fitter than both parents.

Sex is hereditary. If your parents didn’t have it, you won’t either

.

This phenomenon was demonstrated in 2007 by Matthew Goddard at Auckland University in New Zealand. He compared two types of wheat—one that reproduced sexually and one that cloned itself. In stable environmental conditions, both wheat strains reproduced at about the same rate, but when the scientists increased the room temperature to create a harsher environment, the sexually produced strain did much better. Over 300 generations, its growth rate increased by 94%, versus 80% for the cloned wheat.

Sex can be enjoyable and fun, but it is also time-consuming and exhausting. Ultimately, it produces a stronger, fitter species, and that’s the main reason we have it

.

Up until the 1940s, age forty-two was considered to be middle-aged. People aged fifty had only their retirement to look forward

to, and a sixty-year-old was considered to be old. These stereotypes were challenged by Rod Stewart, Mick Jagger, Sean Connery, David Bowie, Cher, Hugh Hefner, Madonna, Joan Collins, and Paul McCartney, to name just a few.

The twenty-first century will be a good time for people aged forty-plus as they were the ones who were born or lived through the 1960s and the 1970s, which have had an enormous impact on modern living and culture. This is the generation that is exploring health and longevity and learning how to turn back the clock on the aging process. Until the latter part of the twentieth century, a typical forty-plus woman was seen as settled, domesticated, and married and was more likely to use a bread slicer than a vibrator. Her life was considered boring and mundane, devoid of romance, sex, and excitement, just like in the Victorian era. Now the role models for women over forty reveal bodies and attitudes more like those of women in their thirties. This is the first generation of humans who refuse to acknowledge aging.

Here are some statistics on the changes in some of today’s societies. These were assembled in 2008 and taken from the various bureaus of statistics and data and national centers of health in up to thirty Western and European countries, including the United Kingdom, Australia, New Zealand, the United States, Canada, Germany, France, Holland, and Spain:

The average age of today’s groom is thirty-four; the average age of a bride is thirty-two. (Add three years to both ages for second marriages.)

The average age of first-time mothers in 2008 was thirty. One in six couples now use IVF for conception because of low fertility rates.

The average age of divorce has risen from 37.6 years in 1988 to 44.2 years in 2007 for men and from 34.8 years to 41.3 years for women.

Around 40% of children are now conceived outside marriage.

Only 36% of couples choose a church ceremony when they marry.

Around 80% of couples in which one partner snores sleep apart.

Results like these have never been seen in past generations of humans, and they highlight a huge swing in our attitudes to relationships.

Humans are increasingly being studied within the evolutionary framework used by animal behavior researchers. The labels for this work include evolutionary psychology, evolutionary biology, human behavioral ecology, and human sociobiology. Collectively, we call these areas “human evolutionary psychology” (HEP) because their shared objective is an evolutionary understanding of why we are the way we are, based on where we have come from. Many HEP researchers began their scientific careers in animal behavior, and consequently HEP research is very similar to other animal behavior research, being based on the principle that human behaviors evolved in the same way behaviors of all animals evolved. In HEP, the researched animal can of course talk, which has both advantages and pitfalls for researchers. Understanding HEP means we can better predict how humans will react or respond.

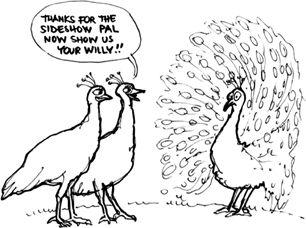

For example, the peacock evolved with brilliant plumage because peahens have always preferred males with bright, colorful, flashy tails. The peahens rejected peacocks with dull plumage because unfit male peacocks cannot grow spectacular tails. This has had the evolutionary effect of breeding out dull-looking males because females would not mate with them.

Just like peahens and peacocks, human sexual strategies for finding a mate operate on an unconscious level. As in other animal species, human mating is always strategic, never indiscriminate—despite what we may like to think. Simply put, women have always wanted men who could provide resources—food, shelter, and protection—and men who failed to gather resources have fewer opportunities to pass on their genes to the next generation.

Since the beginning of formalized medicine in the eighteenth century, doctors have been loath to accept any ideas about human longevity that couldn’t be measured or quantified. Research now reveals that being loved and being in love allow you to live significantly longer and that no other single thing—be it genes, diet, lifestyle, or drugs—can equal love’s effects. Dr. Dean Ornish, author of the Groundbreaking

Stress, Diet and Your Heart

, is a pioneer in research on human longevity and was the first medical scientist to prove conclusively that ailments such as heart disease could be caused or reversed by lifestyle and by having positive, loving relationships in your

life. He reported on the Harvard “Mastery of Stress” study, conducted in the early 1950s at Harvard University, in which researchers gave questionnaires to 156 healthy males to evaluate how they felt about each of their parents, rating their relationship with a parent from “close and warm” to “strained and cold.” Thirty-five years later, it was found that 91% of participants who did not perceive themselves as having a warm relationship with their mothers had been diagnosed with serious diseases in mid-life. Only 45% of participants who perceived themselves as having a warm relationship with their mothers had any major illness. When it came to rating participants’ closeness to their fathers, 82% with low warmth and closeness ratings had developed serious disease, compared with 50% of those who recorded high closeness scores. Among the participants who rated

both

parents low in warmth and closeness, an amazing 100% had been diagnosed with a major disease in midlife.

People who feel loved live longer and enjoy better health

.

Researchers from Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine in Cleveland, Ohio, gave questionnaires to 8,500 men who had no history of duodenal ulcers and then monitored them over a five-year period. The outcome was that 254 men developed ulcers, but astonishingly, the men who answered, “My wife does not love me,” in the questionnaire developed three times as many ulcers as the men whose wives loved them. In another five-year experiment, the researchers tracked 10,000 married men with no history of chest pain (angina). The men who answered “yes” to the question “Does your wife love you?” suffered significantly less angina, regardless of their other possible risk factors. They also found that the higher a man’s health risk category was, the more significant his wife’s love was to his enduring good health. Ongoing

research now shows that emotions play a powerful role as a buffer against things that cause you stress and that lead to illness and disease.

So does this mean that if you had a bad relationship with one or both parents you are doomed to die of cancer, for example? Fortunately, no. Research has also shown that an intimate, loving relationship as an adult brings emotional safety and can offset those early effects of parental deprivation. If, however, people repeat the same relationship patterns they experienced as a child, they can become strong candidates for major illness.

Studies everywhere now show that married people live longer, with lower mortality rates for almost every disease, than single, separated, widowed, or divorced people. The chance of surviving more than five years after a diagnosis of cancer is greater for married people of all races, sexes, and cultures than it is for unmarried people.

Married men live longer than single men, but married men are more willing to die

.

Early studies also show that married people experience better health than couples who choose to cohabit but not marry. This is because marriage carries with it more emotional security than cohabiting, especially for women, as it tells others that the partner is officially “off the market.” Marriage equals less stress and more feelings of security, which promotes an overall healthier immune system. Linda Waite, president of the Population Research Association of America, conducted a study and found that for both men and women, marriage lengthens life span. Married men live, on average, ten years longer than unmarried men, and married women live about four years longer than unmarried women. In summary, married people live longer and have fewer illnesses than unmarried people.

By 2021, one in five U.K. couples will be unmarried, preferring to cohabit

.

For most people, love is a big mystery—especially for men. When a woman uses the term “love,” men have little idea what she actually means. She says to him, “I love you,” and in the next sentence she says, “I love sushi,” followed by “I love my dog,” and “I love shopping.” So now he’s left wondering where he rates against a California roll, clothes shopping, and a Labrador retriever.

“Of course I love you,” he protested. “I’m your husband—that’s my job.”

The problem is that most modern languages have only one word for a wide range of emotions called “love.” Ancient languages had many categories of love and a separate word to define each meaning. The ancient Persians had 78, the Greeks had 4, and there were 5 in Latin, but there’s only 1 in English.

Today, there are seven basic types of love:

Romantic love

—physical attraction, sexual feelings, romance, and hormone activityPragmatic love

—to love your country, your job, shopping, or pizzaAltruistic love

—to love a cause, a god, or a religionObsessive love

—jealousy, obsession, or powerful unstable emotionsBrotherly love

—for your friends and neighborsCommon love

—for your fellow man and othersFamilial love

—feelings of love for children, parents, and siblings

So the first time a woman says to a man, “I love you,” what is he to think? Until just now, his relationship with her was great for him—lots of sex, laughter, and good times. Now he’s picturing commitment, marriage, in-laws, kids, boredom, loss of hobbies, mental torture, eternal monogamy, a potbelly, and baldness. To a woman, love signals monogamy, nesting, family, and kids—all the female priorities that can be scary to men.

A “love map” is a blueprint that contains the things that we think are attractive. This inner scorecard is something that people use to rate the suitability of mates. How we decide who we are attracted to is determined both by the brain’s hardwiring and by a set of criteria formed in childhood. These criteria are based on the things we saw and experienced; such as the way our parents said certain words or phrases; what they thought was exciting, appalling, or distasteful; what our childhood friends thought was good versus bad; what our teachers thought about punishment and reward; and a variety of other seemingly minor things we were exposed to. Scientists who study how we make our partner choices believe that these love maps begin forming at around age six and are firmly in place by age fourteen.