Why Growth Matters (32 page)

Read Why Growth Matters Online

Authors: Jagdish Bhagwati

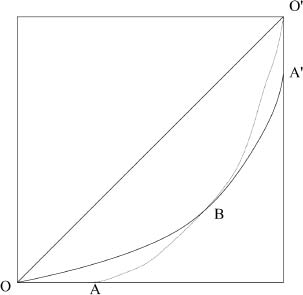

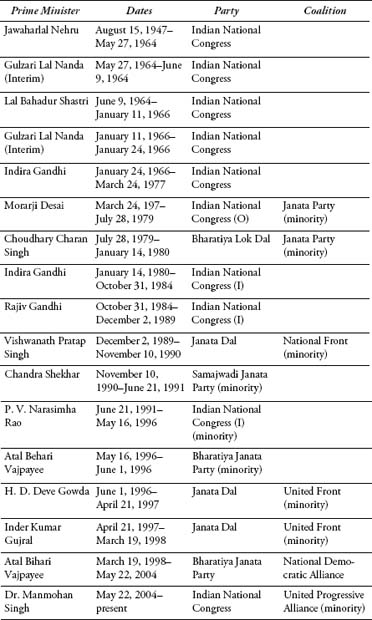

In the first of the above extreme cases in which the Lorenz curve coincides with the diagonal, the income is identical across all households. Identical distribution implies that the bottom 10 percent of the households account for 10 percent of the total income, the bottom 20 percent for 20 percent of the income, and so on. These points are of course on the diagonal. In the second extreme case in which the Lorenz curve coincides with triangle OBO', the distribution is the most unequal it can be. The most unequal distribution implies that all income is concentrated in one household. This means that all households except one have zero income so that the Lorenz curve coincides with the horizontal axis except when we get to the last household, at which point the curve coincides with the vertical axis. The Lorenz curve is thus represented by triangle OBO'. The lower the share of the households at the bottom, the closer is the Lorenz curve to the horizontal axis at the bottom. Likewise, the larger the share of the households at the top, the closer is the Lorenz curve to the vertical axis at the top. Both these factors pull the Lorenz curve away from the diagonal. Therefore, the more unequal the distribution, the farther the Lorenz curve is from the diagonal and therefore the closer is the value of the Gini coefficient to 1.

Figure A2.2. Two Lorenz curves with the same value of the Gini coefficient

Finally, observe that any given value of the Gini coefficient is consistent with infinitely many shapes of the Lorenz curve, so that the frequent references to Gini coefficients across time or regions as measures of inequality must be handled with care. Figure A2.2 illustrates this point. Here we draw two Lorenz curves, OBA'O' as a solid line and OABO' as a dotted line. Because the area between the Lorenz curve and the diagonal is the same in the two cases, the value of the Gini coefficient associated with them is the same. Yet the two Lorenz curves represent very

different distributions of income. The dotted curve shows a large proportion of the bottom households as having no income and hence is associated with a significant volume of abject poverty. The solid line exhibits less poverty at the bottom but is characterized with a high degree of concentration at the top. Most observers would find the distribution represented by the solid line far more acceptable than that represented by the dotted line, though both are associated with the same value of the Gini coefficient.

3

Key Provisions of the Right to Education Act, 2009

â¢

Â

All children older than six years and younger than fourteen years have the legal right to free education.

â¢

Â

The state government and the central government in a union territory in combination with the local authority (municipal corporation, municipal council,

zila parishad, nagar panchayat

, or

panchayat

, as the case may be) have the obligation to provide every child between six and fourteen years of age elementary education meeting

specified norms and standards

by April 1, 2013.

â¢

Â

Specified norms and standards that schools must meet include

Â

»

Â

Studentâteacher ratios of thirty at primary and thirty-five at middle level (to be enforced by the local authority beginning October 1, 2010)

Â

»

Â

Provision of all-weather building consisting of one classroom per teacher, kitchen where midday meals can be cooked, separate toilets for boys and girls, and a playground

Â

»

Â

Library with newspapers, magazines, and books on all subjects

Â

»

Â

Availability of games and sports equipment

Â

»

Â

800 instructional hours per academic year at primary and 1,000 hours at the middle level

â¢

Â

Duties of the local authority include

Â

»

Â

Ensuring the availability of a neighborhood school by March 31, 2013

Â

»

Â

Maintaining records of children up to the age of fourteen years residing within its jurisdiction

Â

»

Â

Ensuring and monitoring admission, attendance, and completion of elementary education by every child residing within its jurisdiction

Â

»

Â

Ensuring admission of children of migrant families

â¢

Â

Â

Every school must achieve the specified norms and standards by March 31, 2013, failing which it will be shut down.

â¢

Â

No new schools should be established without recognition certificate from the authority appointed by the state or central government and every unrecognized school must get recognition within the time stipulated from this authority.

â¢

Â

No child or parent can be subject to any kind of screening procedure for purposes of admission.

â¢

Â

No child can be held back, expelled, and required to pass the board examination until the completion of elementary education.

â¢

Â

No donation or capitation fee at the time of admission is permitted.

â¢

Â

Private schools will have to take 25 percent of their class in grade one from the weaker section and the disadvantaged group of the society and provide free compulsory education until the completion of elementary education. Government will fund education of these children at the rate of per child expenditure in public schools.

â¢

Â

Every teacher is required to attain minimum qualification specified by a centrally appointed authority by March 31, 2015.

â¢

Â

The state government or local authority will set the terms and conditions of service and salary and allowances of teachers.

â¢

Â

No teacher is to engage in private tuition or private teaching activity.

â¢

Â

A teacher will be duty-bound to

Â

»

Â

Maintain regularity and punctuality in attending school

Â

»

Â

Complete entire curriculum within the specified time

Â

»

Â

Assess the learning ability of each child and accordingly, supplement additional instructions as required

Â

»

Â

Hold regular me

etings with parents and guardians and apprise them about attendance, ability to learn, progress made in learning, and any other relevant information about the child

Â

»

Â

A teacher in default of duties is liable to disciplinary action under the service rules applicable to him or her

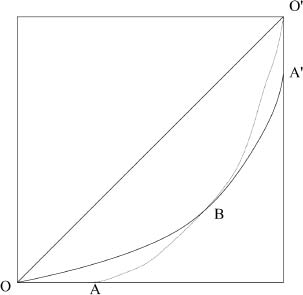

Prime Ministers of India

Preface

1

. In the end, it turned out that

private

savings would also rise as opportunities increased for profitable investment, as demonstrated in the East Asian experience we touch upon below. This undercuts arguments based entirely on the ability to tax to raise

public

savings.

2

. Nearly all developmental economists in the West in the 1950s and early 1960s were rooting for India's success: these included the pioneers of development economics, such as Paul Rosenstein-Rodan. Their “love affair” with India was manifest in their writings and their willingness to work in India through programs that brought in many Western economists, the most prominent example being MIT's program, which brought MIT economists Richard Eckaus and Louis Lefeber, and Ian Little (Oxford), Brian Reddaway (Cambridge), and Trevor Swan (Australian National University) to work in New Delhi. Others included George Rosen and Wilfred Malenbaum.

3

. Thus, China's autarky was a result of Marxist aversion to integration into the world economy, as was the case also with the Soviet Union. In India's case, autarky reflected erroneous economic doctrines rather than ideological politics.

4

. There has been discussion whether the foreign aid inflow adversely affected domestic savings effort. But extensive analysis by Bhagwati and Srinivasan (1975) concludes otherwise.

5

. See Bhagwati, “The Miracle That Did Happen: Understanding East Asia in Comparative Perspective,” 1996; reprinted in Bhagwati

(1999). The stark contrast in the productivity-of-investment of the Soviet Union and of East Asia, which we note in the text, is what made many observers critical of Paul Krugman's argument that East Asia would go the way of the Soviet Union because capital accumulation would lead to diminishing returns in East Asia. In the end, what caused East Asia to collapse, not gradually as the Krugman argument would imply but sharply and dramatically, was huge capital inflows after premature and ill-advised freeing of capital flows and the subsequent outflow of capital.

6

. Panagariya (2008, Chapters 2â4) provides extensive documentation of regulatory policies during the first three decades of Indian development.

7

. This meant that a manufacturer licensed to produce 100,000 cars was forbidden from using a part of his authorized production capacity to produce trucks.

8

. Of course, in economic theory, economists can demonstrate that market losses are compatible with social gains. But while some Indian economists, such as Amartya Sen in the early 1980s, argued this way, the losses in the public-sector enterprises simply reflected inefficient production resulting from the monopoly positions they enjoyed, and the political overstaffing that they were typically subjected to. This unpleasant reality was captured well by John Kenneth Galbraith, who had been ambassador to India under President John Kennedy, when he described the situation as one of “post office socialism.”

9

. Many empirical studies underlie the positive relationship between growth and openness, using postwar data for a much wider range of developing and developed countries. See, in particular, Panagariya (2004). Admittedly this study only establishes correlations, leaving open the issue as to whether trade explains growth or the other way around. But it does establish that policies that bottle up trade will also bottle up growth. Moreover, other studies, most notably Frankel and Rose (2002), establish causation running from trade to per capita incomes.

10

. Panagariya (2008, Chapter 6) compares the experiences of India and South Korea in the 1960s and 1970s, arguing that trade openness was crucial to the latter's success while autarkic trade policies proved fatal to the efficiency of investments and therefore growth in the former.

11

.

Panagariya (2011c) has recently revisited the Taiwanese miracle of the 1960s and 1970s, countering each of the many critiques of authors such as Rodrik (1995) and Wade (1990) and showing that trade openness complemented by a set of market-friendly domestic policies along the lines described in the text above was central to it.