Why do Clocks run clockwise? (23 page)

Read Why do Clocks run clockwise? Online

Authors: David Feldman

assume that the shelf life of their works in bookstores will approximate that of

Tiger Beat

magazine on the newsstand. Those three question marks on our example stand for the three letters that Harper & Row uses to designate which of their printers handled the particular book.

When a book goes into a second printing, instead of redoing the whole copyright page, the printer merely deletes the “1” in the lower right corner and deletes the line that indicates that this was a first printing, if there is one. Some publishers put the lower numbers on the left and the higher ones on the right and omit the year of the printing altogether, but the principle is the same—the lowest number you see always conveys the print-run number.

The public often misunderstands the importance of printings. Ads blare, “Now in Its Fifth Printing!!!” as if a large number of printings guarantees a megaseller. Actually, multiple printings indicate that a book has surpassed expectations, but not necessarily that it has sold more than a book that never went into a second printing.

Submitted by Jonathan Sabin, of Bradenton, Florida

.

176 / DAVID FELDMAN

Why Is 40 Percent Alcohol Called 80 Proof?

Before the nineteenth century, the technology wasn’t available to measure the alcohol content of liquids accurately. The first hydro-meter was invented by John Clarke in 1725 but wasn’t approved by the British Parliament for official use until the end of the century.

In the meantime, purveyors of spirits needed a way to determine alcohol content, and tax collectors demanded a way to ascertain exactly what their rightful share of liquor sales was.

So the British devised an ingenious, if imprecise, method. Someone figured out that gunpowder would ignite in an alcoholic liquid only if enough water was eliminated from the mix. When the proportion of alcohol to water was high enough that black gunpower would explode—this was the

proof

of the alcohol.

The British proof, established by the Cromwell Parliament, contained approximately eleven parts by volume of alcohol to ten parts water. The British proof is the equivalent of 114.2 U.S. proof. More potent potables were called “over proof” (or o.p.), and those under 114.2 U.S. proof were deemed “under proof” (or u.p.).

The British and Canadians are still saddled with this archaic method of measuring alcohol content. The United State’s system makes slightly more sense. The U.S. proof is simply double the alcohol percentage volume at 60° F. For once, the French are the logical nation. They recognize the wisdom in bypassing “proof” and simply stating the percentage of alcohol on spirits labels. The French method has spread to wine bottles everywhere, but hard liquor, true to its gunpowder roots, won’t give up the “proof.”

Submitted by Robert J. Abrams, of Boston, Massachusetts

.

WHY DO CLOCKS RUN CLOCKWISE? / 177

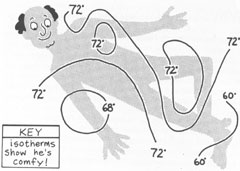

Why Are Humans Most Comfortable at 72° F? Why

Not at 98.6° F?

We feel most comfortable when we maintain our body temperature, so why don’t we feel most comfortable when it is 98.6° F in the ambient air? We would—if we were nudists.

But most of us cling to the habit of wearing clothes. Clothing helps us retain body heat, some of which must be dissipated in order for us to feel comfortable in warm environments. Uncovered parts of our body usually radiate enough heat to meet the ambient air temperature halfway. If we are fully clothed at 72° F, the uncovered hands, ears, and face will radiate only a small portion of our heat, but enough to make us feel comfortable. Nude at 72° F, we would feel cold, for our bodies would give off too much heat.

178 / DAVID FELDMAN

Humidity and wind also affect our comfort level. The more humid the air, the greater ability it has to absorb heat. Wind can also wreak havoc with our comfort level. It hastens the flow of the heat we radiate and then constantly moves the air away and allows slightly cooler air to replace it.

Submitted by Joel Kuni, of Kirkland, Washington

.

Why Do They Call Large Trucks “Semis”?

Semi-

Whats

?

The power unit of commercial trucks, the part that actually pulls the load, is called the “tractor.” The tractor pulls some form of trailer, either a “full trailer” or a “semitrailer.” According to Neill Darmstadter, senior safety engineer for the American Trucking Associations, “A Semitrailer is legally defined as a vehicle designed so that a portion of its weight rests on a towing vehicle. This distinguishes it from a full trailer on which the entire load, except for a drawbar, rests on its own wheels.”

Semi

is short for “tractor-semitrailer,” but most truckers use the term

semi

to refer to both the trailer alone and the tractor-semitrailer combination. Since the tractor assumes part of the burden of carrying the weight of the semitrailer, the “semi” must have a mechanism for propping up the trailer when the power vehicle is disengaged. The semitrailer is supported by the rear wheels in back and by a small pair of wheels, called the landing gear, which can be raised and lowered by the driver. The landing gear is located at the front of the semitrailer, usually just behind the rear wheels of the tractor.

Submitted by Doug Watkins, Jr., of Hayward, California

.

WHY DO CLOCKS RUN CLOCKWISE? / 179

Why Does San Francisco Sourdough Bread Taste

Different from Other Sourdough French Breads?

This Imponderable has been a source of controversy for a long, long time. San Francisco sourdough French bread has exactly the same ingredients as any other: flour, salt, water, and natural yeast. Yet, somehow, it is different: the crust is dark and hard, but crumbly, and the taste more sour than the competition’s.

The usual explanation for the unique San Francisco taste is the Pacific Ocean air, the winds, and especially the fog. Many of the old-time bakers still use brick ovens, and a mystique has built up around them.

The answer, however, can actually be traced to the “starter.”

Whenever a baker makes a batch of sourdough, some of the fermented dough is set aside as a starter, which will be used to leaven the next batch. In this manner, the action of the yeasts is maintained continuously. Some of the older bakeries have strains of starters dating back more than one hundred years.

180 / DAVID FELDMAN

A tourist at Fishermen’s Wharf is literally eating a descendant of the bread consumed by forty-niners.

The use of starters did not originate in the United States. It is believed that the Egyptians, four thousand years before the birth of Christ, were exposing dough to airborne yeast spores to ferment.

Until the advent of commercial yeasts and baking powders, most breads were leavened by using leftover dough from previous batches.

The majority of San Francisco bakeries use a proportion of about 15 percent starter. Little yeast is needed, because the starter contains natural yeast. Sourdough bread made with chemical yeast tends to lack the sourness and tang of the bread made with starter.

Scientists have also tried to pierce the mystique of San Francisco sourdough. In 1970, Dr. Leo Kline and microbiologist colleagues at Oregon State University isolated two organisms in sourdough:

Saccharomyces exiguus

, an acid-tolerant yeast; and a rod-shaped bacterium, resembling lactic-acid bacteria, which they suggested be named

Lactobacillus san francisco

. According to trade newspaper

Milling and Baking News

,

The newly-discovered lactic acid bacteria causes souring. Lactic acids and acetic acids are produced by fermentation of carbohydrates in the flour and provide the sour flavor while the acetic acid primarily keeps spoilage and disease-producing bacteria from growing in the dough.

Yeast cells do the leavening; carbon dioxide gas is produced by yeast during fermentation of carbohydrates in flour. Ethyl alcohol, also produced by the yeast cells, evaporates during cooking. The carbon dioxide provides the light, fluffy texture important in bread, biscuits and pancakes.

The specific bacterium

Lactobacillus san francisco

seems to be a new species, which probably explains why San Francisco sourdough is unique.

Submitted by Donald C. Knudsen, of Oakland, California

.

WHY DO CLOCKS RUN CLOCKWISE? / 181

Does the U.S. Postal Service Add Flavoring to the

Glue on Postage Stamps to Make the Taste More

Palatable?

The Postal Service doesn’t intend the adhesive to have any particular flavor. The glue on U.S. postage stamps comes in only two “flavors,”

and not for reasons of taste.

The first type, used primarily on commemorative stamps, is simply a blend of corn dextrin (a gummy substance extracted from starch) and water. This solution is gentle on commemoratives, which are designed to last longer (in philatelic collections) than “regular”

stamps.

The second type of adhesive, used on regular issues, such as the twenty-two-cent flag stamps, is a blend of polyvinyl acetate emulsion and dextrin. Added to this scrumptious taste sensation is a bit of propylene glycol, used to reduce paper curl.

Is the taste of the stamp glue reminiscent of another flavor? Dianne V. Patterson, of the Postal Service’s Consumer Advocate’s Office, points out that the polyvinyl acetate used for stamp adhesive is the basic ingredient in bubble gum.

Submitted by Joel Kuni, of Kirkland, Washington

.

182 / DAVID FELDMAN

Why Do Wagon Wheels in Westerns Appear to Be

Spinning Backward?

Motion-picture film is really a series of still pictures run at the rate of twenty-four frames per second. When a wagon being photographed moves slowly, the shutter speed of the camera is capturing tiny movements of its wheel at a rate of twenty-four times per second—and the result is a disorienting strobe effect. As long as the movement of the wheel does not synchronize with the shutter speed of the camera, the movement of the wheel on film will be deceptive.

This effect is identical to disco strobe lights, where dancers will appear to be jerking frenetically or listlessly pacing through sludge, depending on the speed of the strobe.

E. J. Blasko, of the Motion Picture and Audiovisual Products Division of Eastman Kodak, explains how the strobe effect works in movies: “As the wheels travel at a slower rate they will appear to go backward, but as the wheel goes faster it will then become synchronized with the film rate of the camera and appear to stay in one spot, and then again at a certain speed the wheel will appear to have its spokes traveling forward, but not at the same rate of speed as the vehicle.” This strobe effect is often seen without need of film. Watch a roulette wheel or fan slow down, and you will see the rotation appear to reverse.

Submitted by Richard Dowdy, of La Costa, California. Thanks

also to: Thomas Cunningham, of Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, and

Curtis Kelly, of Chicago, Illinois

.

WHY DO CLOCKS RUN CLOCKWISE? / 183

Why Does Unscented Hair Spray Smell?

Let’s differentiate between the major formulations of hair spray. A

“regular, scented” formula contains fragrance added to give the spray a distinctive smell. “Fragrance free” refers to hair sprays without any fragrance added at all. Very few hair sprays are fragrance free; these products are designed to be hypo-allergenic for consumers sensitive to any fragrance.

“Unscented” hair spray not only

does

have a scent, but it also has added fragrance, a fragrance designed to mask the chemical base of the product. The difference between “unscented” and “scented” hair spray, then, is that “scented” hair spray contains more fragrance, more long-lasting fragrance, and a fragrance designed to be prominent.

Hair spray is 95 percent alcohol. John Corbett, of the Clairol Corporation, told

Imponderables

that neat alcohol doesn’t smell like a dry martini, but rather like the rubbing alcohol used for cleaning cassette recorder heads. The prospect of spraying rubbing alcohol on your hair is an affront to your nose. The purpose of the unscented spray is to avoid challenging the more expensive, and desirable, fragrance of perfumes or colognes that the customer might apply.